Tbilisi’s Long Fight Against Organized Crime Continues

Tbilisi’s Long Fight Against Organized Crime Continues

Executive Summary:

- The Georgian Ministry of Internal Affairs has made more than 100 arrests over the past few months as part of a nationwide crackdown on organized crime. They are charged with participating in criminal activities and carrying out orders from leaders of the criminal underworld, so-called “thieves-in-law,” who mostly reside in Russia and Europe.

- “Thieves-in-law,” a Soviet and post-Soviet term for leaders of organized crime organizations, has deep roots in Georgian culture and society. Former Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili’s 2005 reforms made a significant contribution to the fight against organized crime.

- Many “thieves-in-law” have been expelled from Georgia, but continue to operate from Europe. They actively participate in business and social processes and have the potential to leverage their influence and social power to undermine the government’s legitimacy.

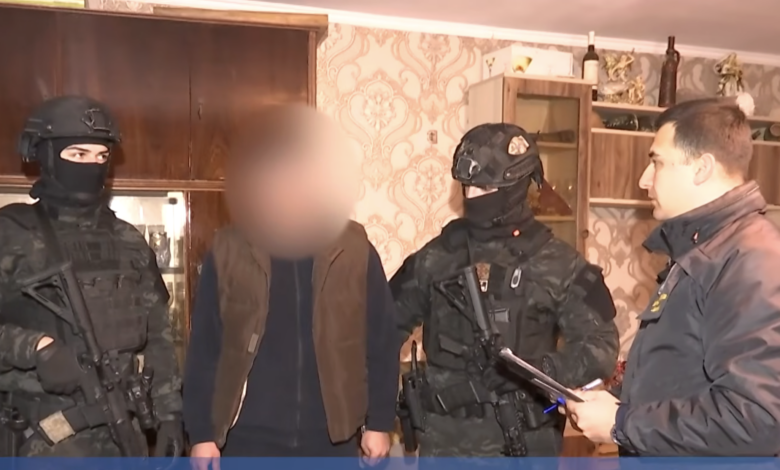

On February 3, Georgian police detained 45 people over alleged links to Georgian organized crime during large-scale operations in Tbilisi and several other regions (Civil Georgia, February 3). Director of the Tbilisi Police Department Vazha Siradze informed journalists during a press conference that the government will charge 15 additional individuals, some of whom are currently in prison and others in absentia. Among those charged are three alleged “thieves-in-law,” a term used in the post-Soviet sphere to describe leaders of organized crime. Siradze said that defendants are charged with crimes including “membership in a criminal underworld, support for the activities of a criminal underworld, and legal theft” (Interpressnews.ge; Info.imedi.ge, February 3). Several “thieves-in-law” were involved in resolving financial disputes between citizens, issuing decisions in favor of one side in line with criminal traditions. According to Siradze, the government is organizing criminal arbitration sessions with the participation of the defendants and other parties to the dispute. Tbilisi is investigating several articles of Georgia’s Criminal Code related to organized crime, which carry prison sentences of up to 15 years (Interpressnews.ge; Info.imedi.ge, February 3). Georgia’s fight against “thieves-in-law” and their influence on politics serves to maintain Tbilisi’s control over the country.

The February operation is only one part of a nationwide crackdown on organized crime in Georgia during the last several months. In December 2025, Georgia’s Ministry of Internal Affairs charged 63 individuals linked to the “criminal underworld,” arresting 49 suspects and charging 14 others in absentia, including five suspected “thieves-in-law” (Info.imedi.ge; Civil Georgia, December 16, 2025). In November 2025, the government arrested 34 individuals and charged seven others in absentia across five separate criminal cases. The Ministry of Internal Affairs asserted that all these cases are related to “participating in or supporting organized criminal networks, including mediating financial disputes, coordinating with thieves in law abroad, and enforcing orders through intimidation and violence” (Civil Georgia, November 5, 2025). The investigation reportedly uncovered evidence of “thieves’ meetings” where participants imposed fines and issued death threats to enforce their decisions (Civil Georgia, November 5, 2025).

The influence of organized crime in Georgia has not substantially decreased following these arrests, as it has deep roots in Georgian society. In a February 7 interview with this author, Davit Avalishvili from the “Experti.ge” website said that the “thieves-in-law” phenomenon—which is markedly different from the Western Mafia, Italian Cosa Nostra, Neapolitan Camorra, and American crime syndicates—is the product of the Soviet penitentiary system (Author’s Interview, February 7). Avalishvili continued:

The administration of the Soviet Gulag camp system needed influential persons to control thousands of prisoners. ‘Thieves-in-law’ were instruments of such control … The influence of ‘thieves’ then spread outside of prisons and camps, taking advantage of corruption in the Soviet system (Author’s Interview, February 7).

According to a recent article in Kommersant, a pro-Kremlin Russian outlet, approximately 75 percent of “thieves-in-law” in the Soviet era and today are Georgian (Kommersant, November 23, 2025). Despite the lack of verifiable data to substantiate this claim, the claim that Georgians make up an outsized proportion of organized crime in the post-Soviet sphere has broad anecdotal support in regional media (Caucasus Watch, July 9, 2019; ACROSS, March 2025). The most infamous Georgian “thieves-in-law” are Zakhariy Knyazevich Kalashov, nicknamed “Young Shakro;” Aslan Usoyan, known as “Grandpa Hassan,” who was killed in 2013; Lasha Shushanashvili, known as “Lasha from Rustavi;” and Tariel Oniani, known as “Taro.”

Petre Mamradze, head of the state chancellery of Georgia from 1995 to 2004, noted another reason for the phenomenal influence of Georgian “thieves-in-law” in his February 8 interview with this author. Mamradze said:

This institution, established in the 1930s, has deep roots in Georgia … Mistrust of Soviet law enforcement persisted, and the importance of [‘thieves-in-law’] increased as the shadow economy developed in Soviet Georgia. [Beginning in the second part of the 1950s] ‘thieves’ became arbiters of disputes between directors of ‘shadow’ workshops and protected ‘shadow’ businessmen from other ‘thieves.’ They received significant income for their services (Author’s Interview, February 8).

Tbilisi’s fight against “thieves-in-law” is part of the legacy of Georgia’s third president, Mikheil Saakashvili. Saakashvili, a polarizing figure who was president of Georgia for most of 2004 to 2013, was a pro-Western reformer whose later years in office were marred by an authoritarian turn and the 2008 war with Russia. Saakashvili signed the landmark “Law on Organized Crime and Racketeering” in December 2005, a turning point in the fight against the influence of “thieves-in-law” (Civil Georgia, December 29, 2005). Article 3 of Georgia’s 2005 “Law on Organized Crime and Racketeering” criminalized participation in organized crime by defining its membership and activities as offenses distinct from the individual crimes committed. The law made intimidation, threats, coercion, promise of silence, involving minors in criminal activity, or using criminal influence to gain benefit, power, or advantage punishable. The law allowed prosecution not only for specific criminal acts but also for membership, leadership, and active participation in organized crime (Legislative Herald of Georgia, December 20, 2005).

General secretary of the United National Movement (UNM) opposition party, Petre Tsiskarishvili, noted in a February 9 interview with this author that the criminal underworld became part of daily life in Georgia after the country gained independence (Author’s Interview, February 9). Tsiskarishvili—a former member of Georgia’s parliament and one of Saakashvili’s closest allies—said that these “legalized thieves” were recognized by the early Georgian government and:

controlled or racketeered businesses, participated in commercial conflict resolutions, and oversaw the criminal networks across the country … The [2005] law, approved by [Georgia’s] parliament, applied to such crime bosses and allowed authorities to charge them for the criminal status they held, which allowed them to coordinate illicit activities (Author’s Interview, February 9).

Tsiskarishvili said that the principle on which the legislation was based became popular and was adopted in other post-Soviet countries, as criminal networks had plagued the region since Stalinist rule in the 1930s. Khatia Dekanoidze, former head of the national police of Ukraine, confirmed, saying that the 2005 Georgian legislation against “thieves” inspired the Ukrainian government and members of parliament to adopt a similar law in 2020 (Author’s Interview, February 8). Lawyers for some Georgian criminals have appealed to European institutions to challenge this law. In July 2014, however, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled that Georgia’s 2005 anti-“thief-in-law” legislation did not breach the European Convention on Human Rights (Civil Georgia, July 15, 2014).

Many “thieves-in-law” fled from Georgia to Russia or Europe after Tbilisi’s 2005 crackdown. In Europe, they created such significant problems for European law enforcement that the European Union reportedly threatened Tbilisi with ending the visa-free regime for Georgian citizens, which began in 2017 (Pappers Politique, May 12, 2025). These alleged threats were unrelated to the ruling Georgian Dream party’s anti-Western turn and the soon-to-be-effective visa restrictions on Georgians with diplomatic passports (Civil Georgia, February 11). The visa-free regime allowed “thieves-in-law” to travel to European countries and remain there illegally beyond the one-year limit, while maintaining their influence in Georgia (Kommersant, April 1, 2019). The Georgian Ministry of Internal Affairs appointed “police attaches” to many European countries. They, along with their European counterparts, however, were unable to prevent “thieves-in-law” from continuing to participate remotely in public life in Georgia (Business Insider, February 21, 2023). Georgia’s police arrest many low-level participants of organized crime, but not its leaders, “thieves-in-law” who often remain beyond the reach of the law.

Saakashvili and his allies took a serious political risk by passing this law and working against powerful organized crime groups. In a February 8 interview with this author, Professor Ghia Nodia from Ilia University said that, until around 2004, and especially in the 1990s, the Georgian government considered “thieves-in-law” not as criminals, but as a part of an alternative, quasi-legitimate system of power and governance (Author’s Interview, February 8). Nodia noted that “thieves-in-law” could exert influence over politics and serve as arbiters in business and social conflicts. They had social authority, and, at least for young men, “thieves-in-law” were regarded as role models. Nodia went on, saying that this system “was basically incompatible with a functional modern state or modern social order” (Author’s Interview, February 8). Saakashvili and UNM took this fight very seriously despite carrying risks. Criminal groups could use their influence and social power to undermine the government’s legitimacy. Sometimes, Nodia said, “when police arrested a mafia boss, the local community was on the criminal’s side, because ‘thieves’ had social capital. That was a problem” (Author’s Interview, February 8). Nodia concluded by arguing that it is necessary to punish criminal authorities and networks, not just individual criminals, because such networks undermine Tbilisi’s monopoly on violence.