The Trans-Himalayan ‘Quad,’ Beijing’s Territorialism, and India

The Trans-Himalayan ‘Quad,’ Beijing’s Territorialism, and India

Introduction

Connectivity linkages between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and trans-Himalayan countries have taken on a new hue with the recent Himalayan ‘Quadrilateral’ meeting between China, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Nepal (MOFA (PRC), July 27). Often referred to as a “handshake across the Himalayas,” China’s outreach in the region has been characterized by ‘comprehensive’ security agreements, infrastructure-oriented aid, enhanced focus on trade, public-private partnerships, and more recently, increased economic and security cooperation during the COVID-19 pandemic.[1] The geopolitics underlying China’s regional development initiatives, often connected with its crown jewel foreign policy project Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), have been highly concerning—not just for the countries involved, but also for neighboring middle powers like India, which have significant stakes in the region.[2]

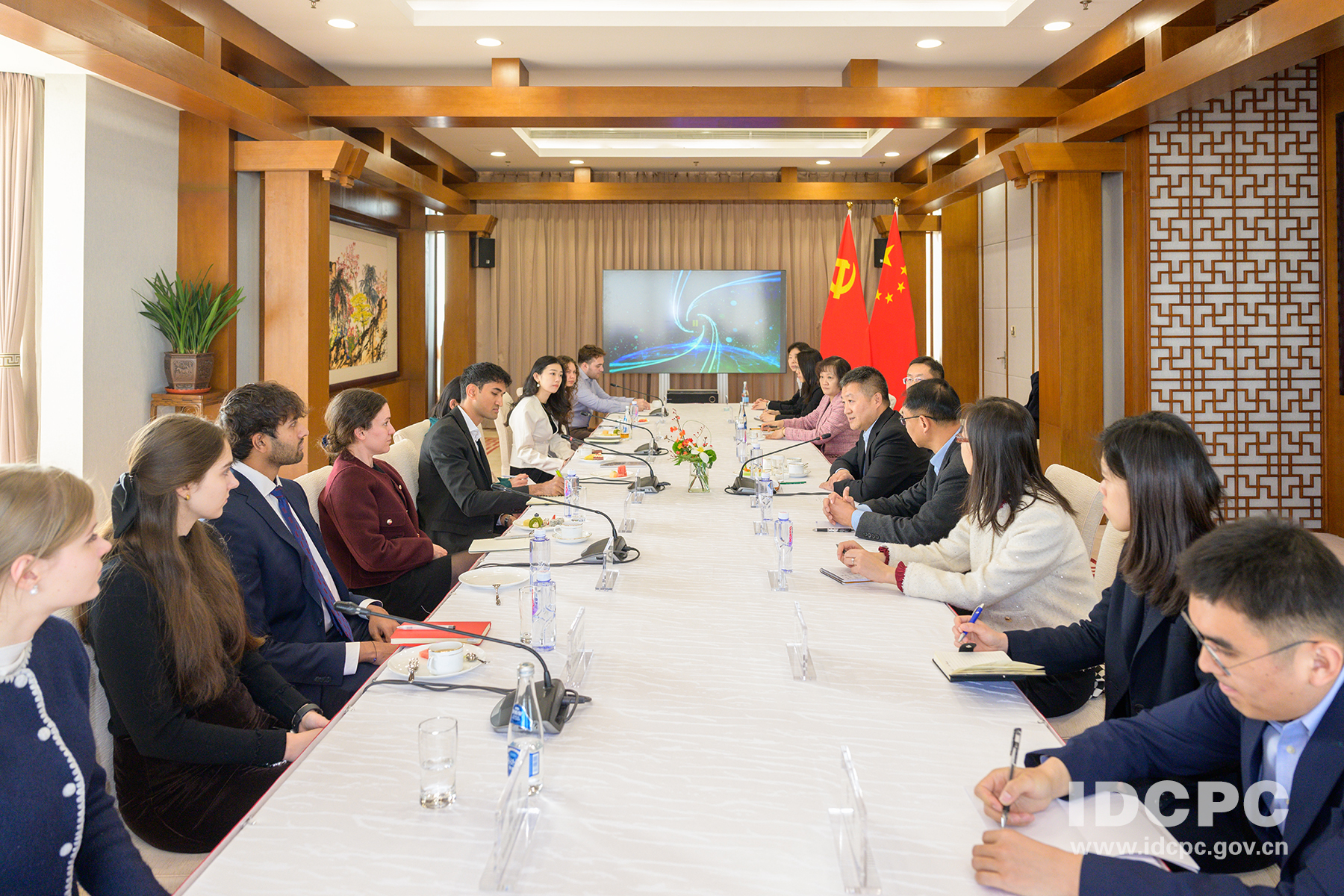

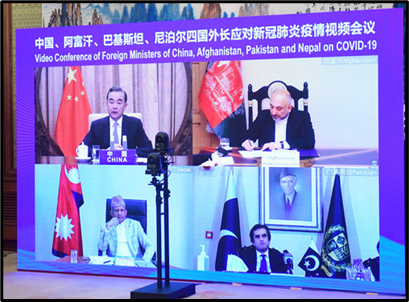

At the Himalayan Quad meeting, foreign ministers from all four countries deliberated on the need to enhance the BRI in the region through a “Health Silk Road”. Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary and PRC President Xi Jinping’s ‘Community of a Shared Future for Humanity’ was cited as justification for facilitating a “common future with closely entwined interests,” and the ministers agreed to work towards enhancing connectivity initiatives to ensuring a steady flow of trade and transport corridors in the region and building multilateralism in the World Health Organization (WHO) to promote a “global community of health” (Xinhua, July 28).

Connectivity linkages between China and the trans-Himalayan region have been significant for China’s foreign policy, economic and security strategies. For China, the region’s utility extends beyond its officially envisaged “win-win” cooperation (MOFA (PRC), April 10, 2018); China’s proactive desire to engage the trans-Himalayan region has much to do with its goals to exert economic leverage, consolidate normative power and extend its political and strategic influence regionally, lending stronger support for its notions of global governance.[3] In this context, trans-Himalayan connectivity initiatives under the banner of the BRI serve an important role in the creation of a Sino-centric regional order. Consequently, the prevalent geopolitics of the region, including India’s policies, are a crucial consideration in the progression of China’s grand infrastructural ambitions (SIIS, May 5, 2017).

Beijing’s economic corridors undermine the historic trans-Himalayan balance of power

Recent years have shown that China is determined to ramp up political, economic, quasi-military and people-to-people exchanges in the region as part of its trans-Himalayan outlook. New Chinese-funded economic corridors such as the Chinese-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and the Trans-Himalayan Connectivity Network (THCM) will not just impact trade, but also have crucial effects on the strategic, social and political landscapes of the host countries that they pass through. The geopolitical implications of China’s increasing regional activities are enormous.[4] Indeed, it could be argued that China’s regional policy has been developed through repeated “invisible incursions” using “religion, ideas, language and culture” to undermine past regional partnerships and reinforce China’s growing cultural and social power in the region (Hudson Institute, October 31, 2017).

China’s economic influence is already strongly felt in Bangladesh and Nepal, which have traditionally fallen under India’s sphere of influence (China Daily, July 5, 2019; CGTN, November 27, 2017). As Beijing seeks closer ties to the smaller South Asian countries, it threatens India’s historic dominance in the region. The situation is expected to worsen if India-China relations continue to decline and hostilities between the two countries continue along the border. The CPEC—which passes through the contested Himalayan border region of Gilgit-Baltistan—is being built mainly by China with the support of both Pakistan and Afghanistan, further undermining India’s influence and raising tensions in the region (Global Times, December 26, 2017; Global Times, August 23).

Closer Sino-Afghan and Sino-Nepali ties fueled by infrastructure diplomacy

China has been interested in adding Afghanistan to its grand infrastructure initiative as early as 2014, and since 2017 it has held a series of trilateral talks with Afghanistan and Pakistan aimed at expanding the CPEC and BRI-related investments in Afghanistan (Dawn, September 8, 2019; MOFA (PRC), July 7). China and Afghanistan have signed agreements to connect the two countries in northern Afghanistan via the Sino-Afghanistan Special Railway Transportation Project and Five Nations Railway Project in 2016, and have also set in motion initiatives connecting CPEC to southern Afghanistan which went into effect earlier this year (Freidrich Ebert Stiftung, August 2018; Xinhua, July 14). China has also invested in the Afghanistan Ministry of Communications and Information Technology (MCIT)’s Wakhan Corridor Fiber Optic Survey Project; the first phase of this plan to create cross-border fiber linkages connecting Afghanistan and China was launched earlier this year (Tolo News, April 23, 2017; Business Wire, May 15).

China’s renewed thrust on trans-Himalayan connectivity extends to Nepal as well. For example, China and Nepal held talks on expediting the Trans-Himalayan Multi-dimensional Connectivity Network (THMCN), a railway line which will link Kathmandu with Gyirong, a town in the south of China’s Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR), during President Xi’s visit to Nepal last October (Global Times, October 12, 2019). The THMCN will pave the way for more profound integration between China and the rest of South Asia, solidify border controls and aid in the economic development and integration of China’s TAR. The infrastructure initiative will pass near Lumbini, which is close to the Indian border, and has raised concerns from Indian strategists (VOA, October 16, 2019).

Since formally becoming a member of the BRI in 2017, Nepal has signed multiple comprehensive agreements facilitating transboundary connectivity with China (MOFA (China), October 13, 2019; IDSA, November 4, 2019). Further integration is being pushed, and the high-level importance given to Sino-Nepalese ties was demonstrated by an essay that Xi Jinping published in three major Nepali newspapers last year. Xi’s article underscored the necessity for China and Nepal to ‘deepen strategic communication’, ‘broaden practical cooperation’, ‘expand people-to-people exchanges’ and ‘enhance security cooperation’ (Xinhua, October 11, 2019). Landlocked Nepal has traditionally relied on India for trade and transit routes. Now, China’s infrastructure diplomacy has promised growth and development, while also providing Nepal with alternative trading routes that ameliorate its reliance on India (Aljazeera, July 29). For China, not only is Nepal’s location geo-economically significant, but its large population of Tibetan residents also plays a crucial role in its importance for China (The Wire (India), October 4, 2019). For the sake of its internal security, China cannot afford to let countries such as the U.S. or India pull Nepal away, and is constantly wary of other nations “waving the Tibet card” (China Brief, September 28).

It is important when evaluating the BRI’s infrastructure projects in South Asia to contextualize it among China’s broader foreign policy narratives. President Xi has repeatedly expressed interest in advancing China’s “peripheral diplomacy” (外围外交, waiwei waijiao) and “good neighbor diplomacy” (睦邻外交, mulin waijiao) (Embassy of the PRC in Grenada, March 19, 2019; People’s Daily, January 5, 2015), complementing trans-Himalayan connectivity policies like CPEC and THMCN. China’s charm offensive—coupled with its massive economic weight—appears to be working. In contrast, India has struggled to manage its ‘Neighborhood Policy’, and has been particularly unsuccessful in demarcating its boundaries with China (MEA (India), July 14, 2017). India-driven connectivity developments have so far been limited due to unsettled boundary issues with Pakistan and Nepal in Kalapani and Susta, respectively.

Pakistan and China’s growing isolationism

The COVID-19 pandemic has given rise to anti-China rhetoric worldwide. With countries like Japan actively moving manufacturing out of Beijing and China-Australia ties reaching an “all time low”, China is finding its international goodwill rapidly depleted (Nikkei Asia Review, April 16; Global Times, June 25; Pew Research, October 6). Ongoing technology and trade tensions with the U.S.; continued human rights abuses in Hong Kong, Tibet, and Xinjiang; renewed tensions in the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea; and negative military and diplomatic posturing with India post-Galwan have further hurt China’s reputation in 2020.

Against this backdrop, China’s push for CPEC must be analyzed in the context of China-Pakistan relations. Beijing has declared its desire to exhibit a “new model of state-to-state relations” between the two countries (Embassy of the PRC in Pakistan, April 10, 2018). Relations between China and Pakistan have always been relatively warm, with Pakistan often siding with China on a variety of matters against India. The India-China-Pakistan trilateral relationship has been marred by a convoluted history of unresolved border disputes and recurrent military confrontations at the India-China Line of Actual Control (LAC) and at the India-Pakistan Line of Control (LOC). Beijing responded poorly to India’s abrogation of Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir, which defined Ladakh as a separate Union Territory last year, and this year, China has renewed its diplomatic and military aggressions in the border region (MOFA (PRC), August 6, 2019; China Brief, July 15). Amid worsening Sino-Indian tensions, the CPEC has been a platform for China to exert influence in the trans-Himalayan region. India’s policy changes last year only served to impede—but not halt—China’s growing regional power. When fully realized, the CPEC will cement China-Pakistan economic relations, further unbalancing the complicated security dynamics of the India-China-Pakistan triangle.

Conclusion

Even though China has tried to couch its ‘Himalayan Quad’ initiative in the framework of infrastructure diplomacy and development, it is impossible not to view the initiative through a security prism. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, China has proposed a four-point action plan for its three Himalayan South Asian friends, offering support through economic, medical and infrastructural aid (Global Times, July 28). The degree to which such aid could diplomatically compromise these countries is yet to be seen, but early missteps in China’s so-called mask diplomacy elsewhere have bluntly demonstrated the strings that are so often attached to its foreign policy initiatives (SCMP, March 28).

China’s investments in trans-Himalayan connectivity have a clear geostrategic and security rationale. It is worth noting that many of the large-scale road projects in the Himalayas seem to be catered towards troop movement in addition to facilitating local transportation. Even the hydropower constructions that the BRI has funded, which are an integral part of the trans-Himalayan power corridors, can be seen as a trademark tool of China’s territorialism and ‘state-making’ (Asia Times, October 4, 2019).[5]

China is seeking to combine economic cooperation with geopolitical gains in the trans-Himalayan region through multiple new assemblages and pathways. The fluid and open-ended nature of the BRI projects have been easily repackaged in China’s post-pandemic diplomacy. In such a scenario, it is imperative for India to abandon its languid foreign policy approach, exercise more pre-emptive authority and delineate its agenda well, not only to secure its border territories but also exude more confidence as a strong middle power in the Indo-Pacific.

Dr. Jagannath Panda is a Research Fellow and Centre Coordinator for East Asia at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (MP-IDSA), New Delhi. He is the Series Editor for “Routledge Studies on Think Asia”. Dr. Panda is the Co-Editor/Author of the forthcoming book “Chinese Politics and Foreign Policy under Xi Jinping: The Future Political Trajectory” (Routledge, 2020). He is also the author of “India-China Relations: Politics of Resources, Identity and Authority in a Multipolar World” (Routledge, 2017), and “China’s Path to Power: Party, Military and the Politics of State Transition” (Pentagon Press, 2010).

Notes

[1] See: Murton, G., Lord, A., & Beazley, R., “A handshake across the Himalayas: Chinese investment, hydropower development, and state formation in Nepal,” Eurasian Geography and Economics, September 2016, 57: 3, 403–432; Sarkar, Sudeshna, “Handshake Across Himalayas”, Beijing Review, Oct. 21, 2019, https://www.bjreview.com/World/201910/t20191021_800182136.html.

[2] Oliveira, Gustavo., Murton, Galen., Rippa, Alessandro., Harlan, Tyler & Yang, Yang, “China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Views from the ground,” Political Geography, May 12, 2020; Voon, P. Jan & Xu, Xinpeng, “Impact of the Belt and Road Initiative on China’s soft power: preliminary evidence”, Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting & Economics, November 3, 2019, 27:1, 120-131.

[3] Callahan, A. William, “China’s ‘Asia Dream’: The Belt and Road Initiative and the new regional order,” Asian Journal of Comparative Politics, May 16, 2016, 1:3, 1-18.

[4] Murton, Galen & Lord, Austin, “Trans-Himalayan Power Corridors: Infrastructural Politics and China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Nepal,” Political Geography, March 2020, 77: 102100.

[5] Gamble, Ruth, “How dams climb mountains: China and India’s statemaking hydropower contest in the Eastern-Himalaya watershed,” February 15, 2019, accessed from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0725513619826204.