Islamic State Obituary Profiles the Life of Slain Maldivan Jihadist Ahmad Nishwan

Islamic State Obituary Profiles the Life of Slain Maldivan Jihadist Ahmad Nishwan

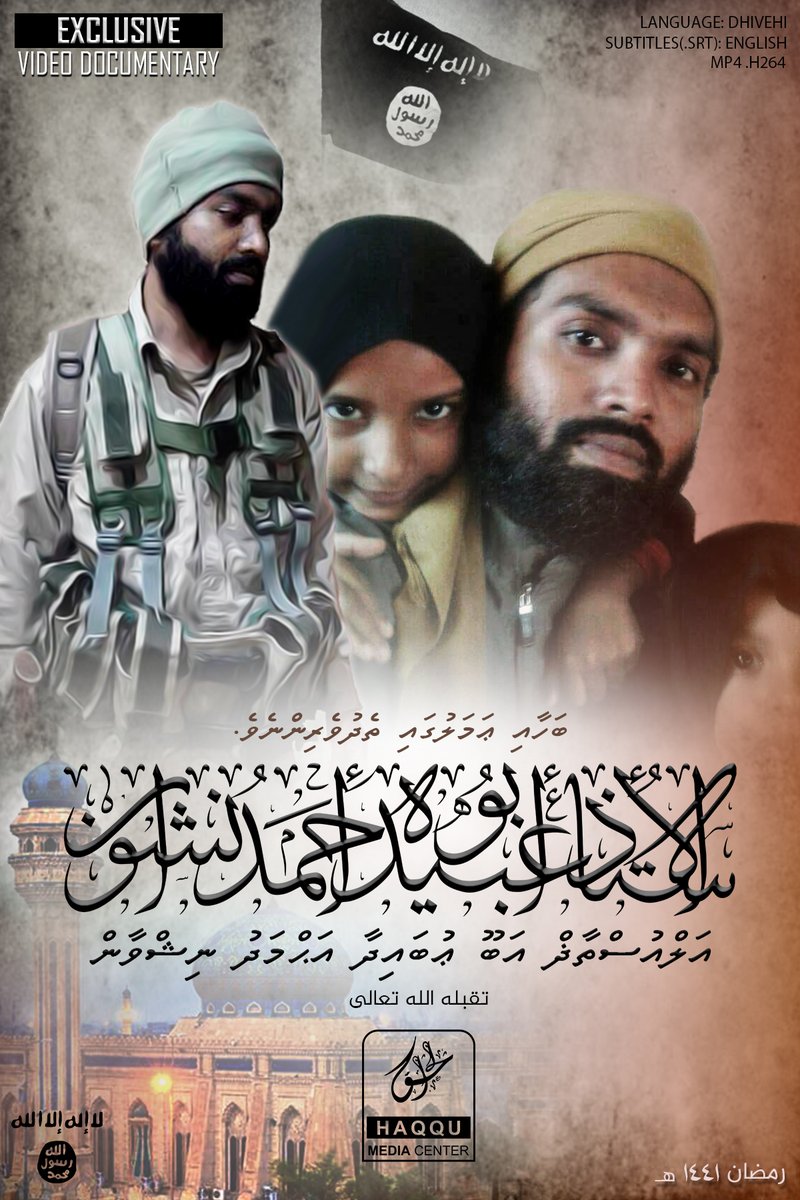

In early May 2020, the pro-Islamic State (IS) media center Haqqu released a documentary on the life of the slain Maldivian jihadist Ahmad Nishwan. The biographical sketch on Nishwan, which is approximately 33-minutes-long, comes amid IS’ increased outreach efforts to Maldivians. Islamic State is using its dedicated Divehi-language media group, Haqqu (meaning “truth”), and other pro-IS platforms, such as the al-Qitaal media center, to urge Maldivians to join the militant group, stage attacks in the country, and campaign for the release of Maldivian war widows and children from refugee camps controlled by the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in al-Hol, Syria.

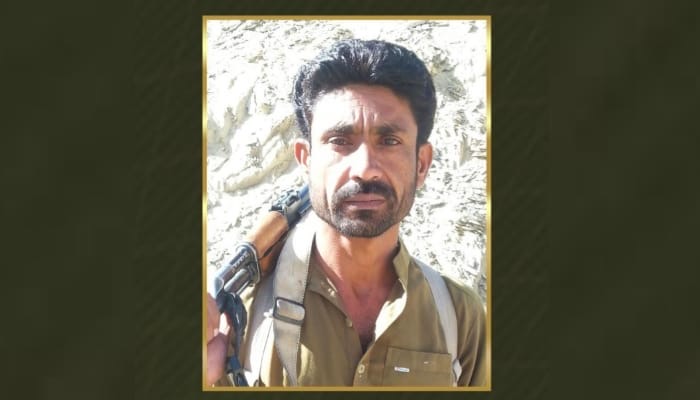

The Divehi-language biographical account, titled “True in their words and action,” was peppered with Arabic chants and narration for greater impact within the targeted country and the wider Arabic-influenced regions of South Asia. [1] The eulogy depicted the honorific Ustaz (teacher), underscoring Nishwan’s expertise in Islamic theology and his position among Islamic State’s Maldivian fighter contingents in the Syrian war theater. Though local media and government officials have remained silent on Nishwan thus far, the biographical information shared through this documentary sheds light on his transformation from an Islamic teacher into a hardcore jihadist.

Born and brought up on Maradhoo island, located in the Addu Atoll, Nishwan completed his Islamic schooling in Addu city. In 2005, at the age of 20, he traveled to Yemen to undertake higher education in Islamic Law and jurisprudence. According to the documentary, he was primarily influenced by the teachings of al-Qaeda ideologue and influential jihadist Anwar al-Awlaki. During his stay in Yemen, Nishwan even met him. Also, though the documentary was silent on when and how he met Awlaki, it is possible that he encountered the al-Qaeda cleric at al-Iman University, Sanna, before August 2006, when the Yemeni authorities detained al-Awlaki for a couple of years. Similar to Awlaki’s career, Nishwan returned to the Maldives and engaged in further Islamic study, becoming a religious teacher in Addu city. Similarly, Awlaki returned to Shabwa in southern Yemen, sacrificing his promising career in the United States and United Kingdom in 2004 for Islamist activities.

Upon returning to the Maldives from Yemen, Nishwan’s Islamic activism increased substantially, fueled by social media and publishing tools like Facebook and WordPress. He engaged in virtual discourses on Islamic doctrines, speaking out against the government’s anti-Islam policies, and was also active in spreading news of ongoing jihadist developments. Traces of his Salafi-jihadist messaging on his now-defunct Facebook pages can still be found on the internet. This is one example of Nishwan’s inclination towards the ideals of Islamic State before he joined the transnational jihadist group in Syria in July 2015. It underscored how Nishwan, already a “hajurite haddadi” extremist, turned into a hardcore “takfiri Kharijite” (Al Hajuri, December 06 2014).

The Haqqu video also highlighted his Divehi-English language WordPress blog, Salafi Media MV, which mostly contains theological literature dated before October 2015. Nishwan was subsequently killed in Ramadi, Iraq, in a U.S. airstrike. The documentary noted how his wife and two daughters also died in March 2019 in Baghuz during a coalition airstrike. The other two surviving daughters are presently in al-Hol refugee camp, along with thousands of (IS-linked) war widows and their family. This information corresponds with ground reports from al-Hol, where Maldivian authorities learned that over 30 Maldivians were living in dire conditions in refugee camps and detention facilities in Syria and have requested repatriation (Sun, April 27).

Nishwan was one of the first Maldivians to pledge allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the late leader of the IS caliphate in Syria and Iraq that emerged in 2014. Though the documentary noted that Nishwan initially plotted lone-wolf strikes in the Maldives targeting American tourists or officials visiting the island nation, he failed in his attempts. Later in July 2015, he traveled to IS-held territories in Iraq and Syria with his pregnant wife and three young daughters. The documentary also claimed that, despite his ideological and military training under the IS field command, due to poor health he was engaged only in propaganda activities and became part of the Haqqu media center. His knowledge of Islam and jihad, with expertise in the Divehi and Arabic languages, made him an asset to the IS propaganda arm.

The local Divehi language unit emerged back in 2014 as a publishing platform for pro-IS materials and translations. It released jihadist literature and songs (naseeds) primarily to attract Maldivian youth by romanticizing jihad and martyrdom. Like Nishwan’s biography, Haqqu published similar sketches glorifying Maldivian jihadists and their life stories to serve as a motivation for jihad for the cause of the caliphate. It released a similar video featuring a slain Maldivian jihadist with the nom de guerre Abu Ikrimah in early February 2016 (Haqqu Media/Archive, February 2, 2016). Again, in late July 2017, it released a detailed anti-Maldives video titled “Glad Tidings to the Strangers,” promoting Maldivian fighters who died fighting alongside Islamic State in Syria and Iraq. It also featured Maldivian jihadists who had earlier been members of al-Qaeda in Waziristan, Pakistan, and later joined the caliphate. This video featured Nishwan briefly alongside at least four Maldivians who died in Syria (Haqqu Media Centre, Archive, August 1, 2017).

Since its inception, the Haqqu media center has played a vital role in radicalizing Maldivians, and it is still luring them towards the cause of the crumbled IS caliphate.

The transnational jihadist group established its foothold in the scenic Maldives for the first time in July 2014. Early ideological efforts were manifested through randomly raised IS flags or insignia in protest rallies or in city squares. Since mid-2019, an increase in IS activities emerged in the Maldives. In October 2019, police arrested a U.S. sanctioned terrorist, Mohamad Ameen, who was recruiting fighters for IS (Edition, October 24; US Treasury (OFAC) September 10, 2019). A month after, in November, several Maldivians fighting alongside Islamic State-Khurasan province, the group’s branch in Afghanistan, were taken into custody by Afghan forces.

This past April 15, almost six years into its shadowy presence in the Maldives, IS claimed its first attack. Unidentified local affiliates used incendiary weapons to set five government-owned boats on fire, including a sea ambulance and police patrolling vessel in Mahibadhoo harbor in Alifu Dhaalu Atoll (One Online, April 15). IS said in a statement that the boats belonged to the “Apostate Government of the Maldives and its loyalists.” Before this arson attack, in early February 2020, an IS-inspired stabbing spree injured three foreign nationals. Though the group did not claim the knife attacks initially, it praised the incident via a publication called Sawt al-Hind (Voice of Hind), published by the Indian branch of IS. It extolled the “Lions of Khilafah” in the Maldives and urged Muslims of neighboring countries to follow their example. The al-Qitaal media center publishes the Voice of Hind magazine, an official outlet of the pro-IS jihadist group Ansar ul Khilafah in Hind.

The video messages chronicling the life and journey of Maldivians certainly sheds light on how they have sacrificed material possessions for the cause of the caliphate and traveled to Iraq and Syria during the heights of the conflicts there in 2014-2016. Ironically, the steady stream of foreign fighters to the caliphate was ignored by the Maldives’ national government as well as its mainstream media. Initially, media coverage of Maldivians joining the transnational jihadist groups took place, especially by now-defunct independent news portals such as Minivan news and Maldives Independent, but the issue has often been swept under the rug and never received any serious attention until now. It should be noted that IS rival al-Qaeda also attracted Maldivians into its fold, several of whom have died in Syria and Iraq.

IS’ aggressive Maldives-centric campaign through media units like Haqqu has certainly exacerbated the extremist trend in the Maldives, and biographical documentaries like Nishwan’s will continue to play a substantial role in fueling local jihadist sentiments long after his death.

Notes

[1] “True in their words and action – al-Ustaz Abu ‘Ubaidah Ahmad Nishwan” May 02, 2020, https://archive.org/details/abu-ubaidah-1080p (Accessed on August 16, 2020).