Mukhtar Robow “Abu Mansur”: Former Spokesman of al-Shabaab Caught in the Middle of Nowhere

Mukhtar Robow “Abu Mansur”: Former Spokesman of al-Shabaab Caught in the Middle of Nowhere

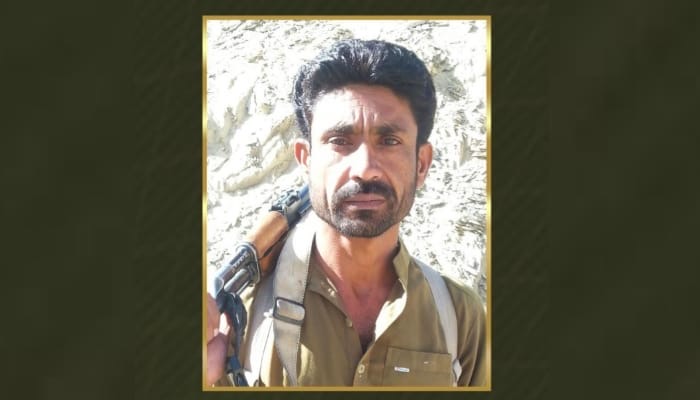

When al-Shabaab grew to prominence during the Ethiopian invasion of Somalia in 2006, Shaykh Mukhtar Robow “Abu Mansur” led the group’s propaganda war aimed at ousting Ethiopian forces and the Somali Transitional government troops from southern Somalia. He was the spokesman for the al-Qaeda inspired group – and the only top commander in that group – which has been blamed for the assassinations of dozens of journalists – who is affable with the press. Unlike other al-Shabaab leaders, Robow, a tall, bearded 45-year-old man with a $5 million bounty on his head, is comfortable in front of the camera and favors being photographed with his AK-47, which he carries in public. Indeed, such charisma made him popular with Somalis and he was often referred to as the group’s most prominent leader before a leadership dispute forced him into hiding (Hiiraan.com, November 17).

Other al-Shabaab co-founders such as the group’s first leader Adan Hashi Ayrow (who was killed in a U.S airstrike in 2008), his successor Ahmed Abdi Godane (a.k.a. Shaykh Mukhtar Abu Zubayr) and Ibrahim Haji Jama “al-Afghani” (who was assassinated by Godane’s Amniyat fighters, the intelligence division of the group, last year due to internal power struggles) had remained little known and were never seen in public. These three men and Robow were former members of Somalia’s al-Itihad al-Islamiya (AIAI – meaning Islamic Unity), an armed organization that formed in the 1980s and sought to establish an Islamic state in Somalia. They then established al-Shabaab, which means “the youth” in Arabic, in 2003, but the group publically emerged in 2006 (VOA Somali, November 2011).

Ayrow, who was the mastermind behind the group, recruited Robow to travel to Afghanistan where “the Islamic emirate of the Taliban was strong at that time” in order to train, gain more battlefield experience and of course help the Taliban and al-Qaeda, according to Robow. [1] As a result of his time in Afghanistan, Mansur often wears a turban.

Before he traveled to Afghanistan, Robow used to run AIAI’s training camp in Somalia’s Hudur town, about 420 kilometers southwest of the capital Mogadishu. He launched the camp known as al-Hudda immediately after he returned from Sudan in 1996, after studying Islamic Shari’a at the University of Khartoum. The purpose of the camp was to recruit new blood from Bakool and Bay regions at a time when the group was suffering severely from repeated attacks by Ethiopian forces. AIAI was desperately in need of foot soldiers to continue its war against Ethiopian troops in the border region and against warlords inside Somalia to uphold its declining influence. Though AIAI slowly disappeared and lost its formal structure, Hudur, which is about 90 kilometers (56 miles) from the Ethiopian border, remained a training base for militants until allied Somali and Ethiopian forces seized it five months ago (Daily Nation [Nairobi], September 29, 2013; Radio Mogadishu, March 7).

Robow then began working side by side with Adan Hashi Ayrow in the secret recruitment of young Somalis for what would become al-Shabaab in order to revive “the seed of the jihadi project,” referring the lost objectives of al-Itihad al-Islamiya. When the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) was established in 2006, al-Shabaab got a long awaited opportunity and became the group’s military wing by providing hundreds, if not thousands, of young fighters who had been recruited and trained for years to establish an Islamic state in Somalia. Shaykh Robow was appointed as the deputy defense minister of the ICU administration, which controlled most of the territories in the south and central parts of the country after ousting the warlords that overthrew the government in 1991. He became the spokesman for al-Shabaab when the Ethiopian invasion overran the ICU administration in 2007. [2]

Robow remained quite close to Ayrow, who Mansur often refers as his mentor, until Ayrow’s death. Given the close relationship, Mansur was thought to be the successor. It is widely believed that he briefly assumed the leadership of the group immediately after the American missile strike killed Ayrow. The circle of al-Shabaab leadership did not see Mansur as a direct replacement of Ayrow, however. They wanted a low-profile leader and purveyor of global jihadi ideology – qualities Robow does not possess. He is considered to be a religious moderate and Somali nationalist and since he is popular, or at least well known in Somalia, he does not have a low profile (Somali Mirror, May 21, 2009).

Speaking to al-Jazeera Arabic in February 2009, Robow declared himself as a nationalist-Islamist figure within al-Shabaab by disavowing claims made by other members that the group will be implementing Islamic law in Alaska:

Explaining his point further, he added that he would first concentrate on instilling law and order according to Shari’a in Baidoa, his hometown and the regional capital of Bay region. “Afterwards, I will go to Diinsoor which is among [the] towns in Bay Region and I will also sort it out that way,” he added. [4]

Robow has a reputation of being a leader who respects the clan system in the community and is open to discussions and interactions with clan leaders. Unlike other figures in al-Shabaab, he interacts with clan elders. This made him not only popular with his Rahanweyn kinsmen, but also with other clans in southern Somalia.

When al-Shabaab fighters seized the strategic town of Baidoa in January 2009, just hours after Ethiopian troops withdrew, Robow gave safe passage to his clan’s Transitional Federal Government (TFG) members, including a well-known warlord and opponent of al-Shabaab, Muhammad Ibrahim Habsade, who is a member of the country’s parliament and former minister of land and air transport. Robow’s Digil and Mirifle clan elders offered to take control of the town in exchange for giving safe passage to their leaders. He accepted it, but his decision infuriated the hardliners of al-Shabaab who perceived this as clan favoritism (Hiiraan.com, January 27, 2009).

Ahmed Abdi Godane, another Afghan war veteran who was never seen in public, never photographed and never spoke publically, succeeded Ayrow in 2009. He replaced Robow with Shaykh Ali Mohamud Raage as the spokesman of al-Shabaab. That was the beginning of al-Shabaab’s transformation from a local Islamist group to a notorious and brutal regional jihadi organization. Godane, who studied accountancy in Pakistan, stood at the apex of the group’s political, military and administrative hierarchy (see Terrorism Monitor, August 10, 2012).

Godane’s leadership style and global jihadist ambitions created ideological and leadership disputes that divided al-Shabaab into two factions – global jihadists and local nationalists. Mansur allied with Shaykh Hassan Dahir Aweys, the former leader of the now defunct independent Islamist movement Hizb al-Islam that merged with al-Shabaab in 2010, and became a forerunner of the group’s nationalist-Islamists advocating for the replacement of Godane. That alliance, however, only increased Godane’s determination to consolidate his command of al-Shabaab by replacing veteran leaders with junior officials who show blind loyalty to him. He has also built a well-paid and well trained praetorian guard known as Amniyat, which is supposed to spy on and assassinate government officials, but also targets rival officers within al-Shabaab (Garowe Online, October 6, 2010).

Godane’s consolidation of power and his willingness to use violence against opponents and critics within the group turned other hardliners and foreign jihadists against him. Al-Shabaab’s other surviving co-founders, Ibrahim Haji Jama (a.k.a. al-Afghani) and Moalim Burhan and American-born jihadist Omar Hammami (a.k.a. Abu Mansur al-Amriki, who was perhaps the most well-known al-Shabaab propagandist because of his English jihadist rap videos) all joined hands with Mansur to bring down Godane (see Terrorism Monitor, August 9, 2013).

Al-Afghani, who, like Godane, is from the Isaaq clan, which is prominent in the breakaway northern region of Somaliland, began to present himself as an alternative leader and potential successor to Godane. However, al-Shabaab leader’s acted fast and ordered his elite hit squad to kill al-Afghani, who had a $5 million U.S. bounty on his head, and Burhan in the coastal town of Barawe when the two men met to finalize their attempt to overthrow Godane. The assassination of these influential leaders was seen as Godane’s last attempt to send a warning to his remaining opponents. That led Shaykh Hassan Dahir Aweys, a former army colonel and a hero of the 1977 Somalia-Ethiopia war, to escape from Barawe by boat and surrender to the Somali government. Two months later, Godane’s hit squad then killed two foreign jihadists, al-Amriki, who was on the FBI’s Most Wanted List with a $5 million reward for his capture, and Osama al-Britani, a British citizen of Pakistani descent, who was also a focal point of foreign jihadists opposing Godane (IPS, October 22, 2013). Al-Amriki was the first al-Shabaab figure to bring the group’s internal division into the public eye by posting a short video clip on the internet in 2012 in which he said his life may be endangered by other members of the group due to some differences (see Terrorism Monitor, May 4, 2012).

Shaykh Mukhtar Robow is now the only remaining major opponent of Godane still free and alive because he has hidden in the southern Bay and Bakool regions, the home turf of his Rahanweyn clan, where his forces have been engaged in battle with Godane’s since last year. Mansur has few options; he cannot rejoin the Godane-led al-Shabaab, but surrendering to the government is also unappealing since they betrayed Shaykh Aweys after his surrender by keeping him under house arrest (see Terrorism Monitor, August 9, 2013).

Prior to the U.S. bounty being placed on his head, Mukhtar Robow was in contact with clan leaders to negotiate the possibility of turning himself in under a government amnesty program (see Terrorism Monitor, August 9, 2013). The bounty ended that possibility because he is afraid to be handed over to the United States. His options are to remain in the lines between the government and Godane rather than the risk of being handed over to the Americans and face public humiliation.

Muhyadin Ahmed Roble is a Nairobi-based analyst for The Jamestown Foundation’s publication Terrorism Monitor.

Notes

1. Shabaab al-Mujahideen Movement, “O’ Abu Muhsen! You Gained in the Deal,” July 24, 2008, https://www.alhesbah.net/v/showthread.php?t=186803.

2. Somalitalk.com, retrieved July 14, 2014, https://somalitalk.com/taariikh/somalia/.

3. Al-Jazeera’s interview with Shaykh Mukhtar Robow “Abu Mansur,” Baidoa, February 26, 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G9Mc03aIDaA.

4. Ibid.