PRC Attempts to Shape Norms at UNHRC

Executive Summary:

- After years of focusing efforts on defending its own human rights record, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has shifted its attention on the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) to shaping norms and advancing a more assertive agenda.

- The PRC has pursued varying tactics to do so, such as framing its initiatives in broadly agreed upon terms, seeking to limit language around accountability and protections against transnational repression, and invoking “wolf warrior” rhetoric.

- The PRC continues to see challenges to advancing it’s agenda in the UNHRC, but growing support from the Global South and peer authoritarian states has already led to political victories.

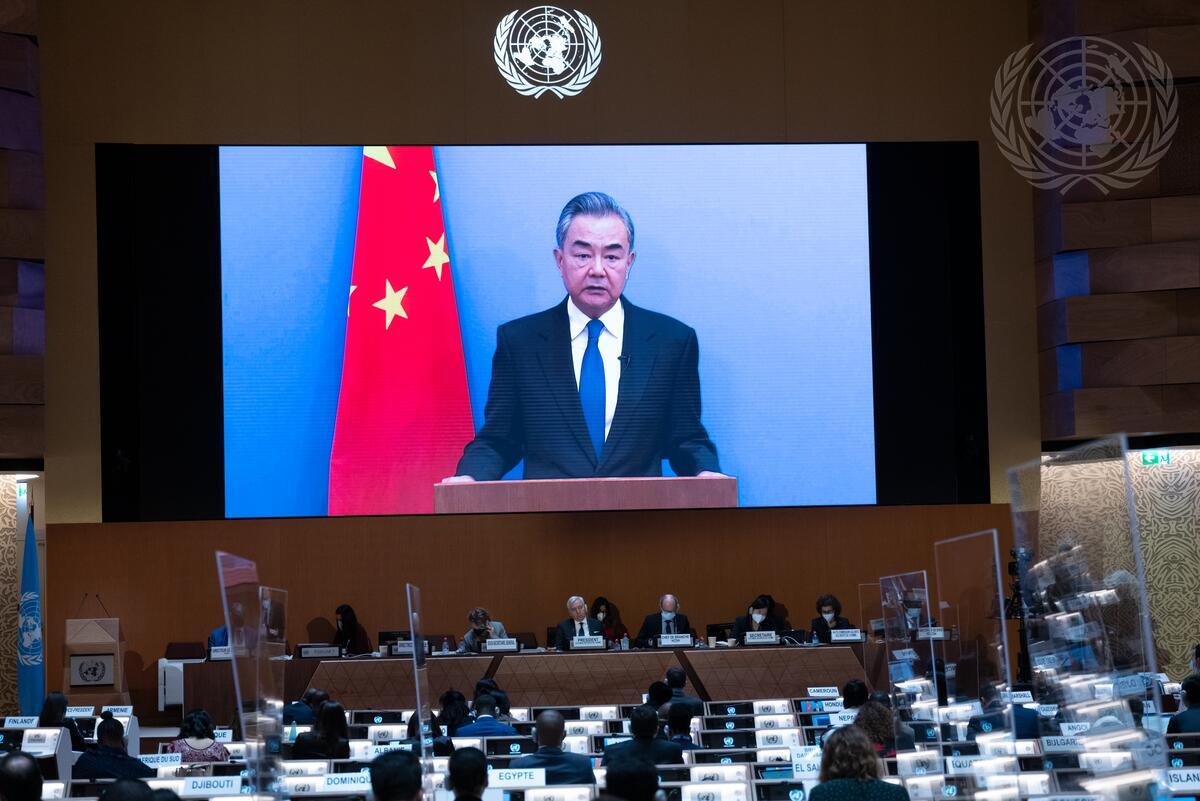

In response to the U.S. withdrawal from UN agencies in January 2026, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) spokesperson Mao Ning (毛宁) reiterated Beijing’s commitment to the “core role” (核心作用) of the United Nations in international affairs (MFA, January 8). The PRC is deeply engaged with the UN, but this engagement is driven in part by a desire to alter the international system in ways that more closely align with its preferences. This is particularly true in the case of the international human rights regime, where the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is pursuing greater prominence in the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) through a multi-pronged approach. This includes a varied diplomatic posture, framing PRC initiatives with innocuous language that obscures its intentions, and resistance to resolutions that seek to strengthen rights with which Beijing disagrees.

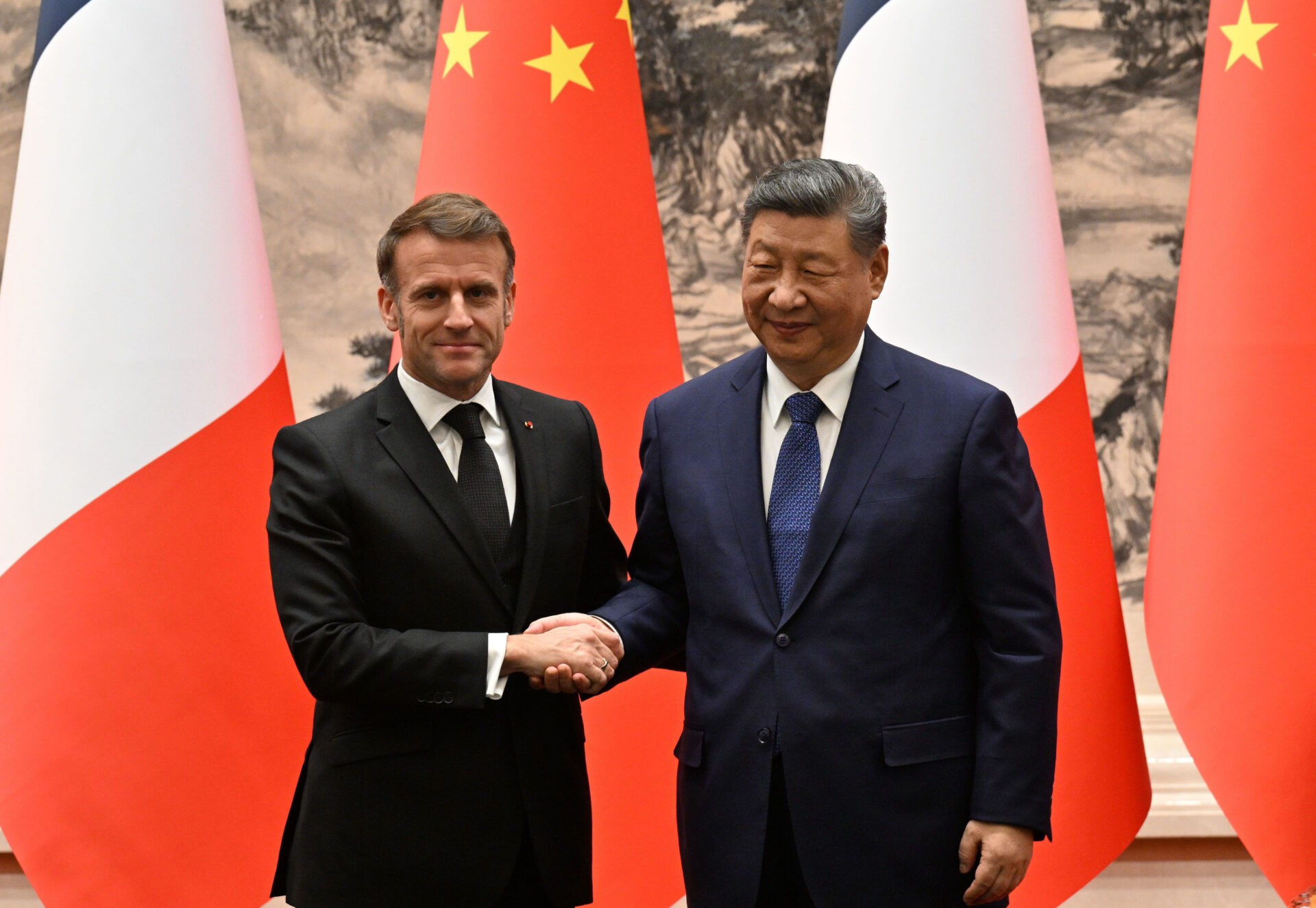

General Secretary Xi Jinping first indicated a shift toward a more assertive posture when he proposed efforts to “build a community of common destiny for mankind and achieve shared and win-win development” (构建人类命运共同体,实现共赢共享) at the HRC in 2017 (Xinhua, January 19, 2017). Since then, the PRC has expanded its engagement, shifting from a low-profile approach focused on defending its own record to a more assertive posture as it seeks to shape the international human rights regime.

Promoting CCP Concepts in the UNHRC

Many of the PRC’s recent resolutions contain phrases derived from Chinese Communist Party (CCP) ideology, including Xi Jinping Thought. Such phrases include “community of common destiny for mankind” (人类命运共同体), “mutually-beneficial cooperation” (互利共赢), and “people-centered approach” (以人为本). [1] While these phrases sound innocuous, they embody concepts that run contrary to certain international human rights norms and principles enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UN, accessed January 29).

“Mutually-beneficial” or “win-win” cooperation are phrases Xi first used in 2013 during a meeting at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations. Xi spoke of the need to build a “new type of international relations” (新型国际关系) (China Brief, April 25, 2013). When the PRC first proposed a UNHRC resolution in 2018 on “Promoting the International Human Rights Cause through Win-Win Cooperation,” other countries had numerous questions and reservations about the term (Human Rights Watch, March 5, 2018; International Committee of Jurists, March 9, 2018). “Mutually beneficial” cooperation suggests that states should cooperate on human rights, rather than holding each other accountable in cases of severe rights abuses.

“People-centered” has been a popular CCP phrase since the early 2000s. According to the Berlin-based nonprofit The Decoding China Project, it is used to “critique of the prevailing global human rights framework” that focuses on individual rights (Decoding China Dictionary, accessed January 27). A 2020 resolution that the PRC tabled at the UNHRC on “people-centered approaches in promoting and protecting human rights” failed to obtain sufficient support and was withdrawn (see Table 1 below). But Beijing has persisted in its attempts to sideline individual and ethnic rights, putting focus instead on “prioritizing societal goals over personal liberties” (China Decoding Dictionary, accessed January 27). The council adopted a PRC-sponsored resolution in fall 2025 on promoting economic, social, and cultural rights (Xinhua, October 7, 2025; OHCHR, January 27). [2] While promoting such rights appears positive and productive, the focus of the resolution is emblematic of efforts to draw resources and attention away from civil and political rights, where the PRC’s record is particularly poor.

Strategies Have Varied Over Time

Since 2017, the PRC appears to have tested and adapted strategies and postures in the HRC to exert greater influence. Its approach seems to be determined by a combination of the PRC mission leadership’s diplomatic style, the environment in the Council, and pragmatism, as it seeks to secure its interests in the Council. At the more aggressive end, this has included actively resisting concepts that oppose the CCP’s agenda and adopting “wolf-warrior” rhetoric. At more subtle times, it has shrewdly sought to conceal its intentions by, for example, framing initiatives in broadly agreed upon terms. The PRC first employed this practice after the violent crackdown in Tiananmen Square in 1989 when it pedaled dialogue and cooperation as the preferred means to advance rights in order to deter countries from supporting resolutions on the PRC’s record. The PRC’s efforts “serve crystal-clear purposes: to insulate states from accountability mechanisms, to eliminate a role for independent civil society, to promote anti-rights norms, and to deter states from challenging it in these venues,” according to Sophie Richardson, co-executive director of Chinese Human Rights Defenders (author interview, December 23, 2025). PRC-initiated resolutions risk distracting from and undermining long-standing human rights principles. The PRC has had some success on this front. In June 2020, it passed a landmark resolution on “promoting mutually beneficial cooperation in the field of human rights.”

The PRC has become increasingly assertive during negotiations and discussions on other resolutions to shape and control the narrative in the UNHRC. A Western European diplomat noted that the PRC coordinates with other authoritarian states to weaken the text of UNHRC resolutions, especially those that strengthen civil and political rights and accountability mechanisms. This often includes resisting protections for human rights advocates or including language about sovereignty to limit the ability to hold countries accountable (author interview, May 27, 2025). Another diplomat referenced PRC diplomats’ efforts to shape the Human Rights Defenders’ resolution, which has enjoyed the Council’s support since 2013 and is intended to protect those who engage in human rights advocacy (A/HRC/RES/58/23), and their particular focus on the language surrounding “transnational repression” (author interview, May 26, 2025). The PRC opposed this term during the deliberations on the resolution because of its record engaging in such activity.

PRC Faces Challenges and Sees Growth

As shown in Table 1, the PRC has already successfully secured adoption of resolutions that endorse its ideas. Despite these successes, there is evidence to suggest that the appeal of some of its values is limited. While Beijing has passed nine resolutions in less than a decade and is slowly shaping the substance of the HRC, there are instances in which other nations maintain reservations. PRC diplomats have had to withdraw resolutions at the last minute in light of such concerns, despite strenuous efforts to secure broad consensus, often by courting Global South countries, including invoking a sense of solidarity with the developed world (The Diplomat, October 9, 2024).

The PRC has often been able to secure votes due to its longstanding courtship of the Global South and its consistent defense of many of the most repressive countries in the world (Inboden, 2021). [3] For example, the 2021 resolution “Promoting Mutually Beneficial Cooperation in the Field of Human Rights” was jointly introduced along with Belarus, Cuba, Egypt, Iran, the Syrian Arab Republic, and Venezuela, in an attempt to redefine norms and principles to the advantage of those countries. The PRC often gets broader support from the Global South in part because of Beijing’s growing economic and political clout, and a shared interest in defending state sovereignty. However, this can have a deleterious effect on the international human rights regime.

Conclusion

After years maintaining a low-profile role within UN human rights bodies, the PRC is a more active force under Xi, proactively injecting Party ideals and preferences into the international human rights regime. The PRC has been on a steady path building its influence in the UNHRC in particular since 2017. Its strategies have brought many of the CCP’s ideological concepts into the international mainstream, and these efforts now risk weakening international human rights norms and principles.

Table 1: PRC Resolutions at the Human Rights Council Since 2017

| Resolution Title | Date and Session | UN Document Number | Outcome |

| The contribution of development to the enjoyment of human rights A/HRC/RES/35/21 | June 2017, 35th | A/HRC/35/L.33/Rev. 1 | Adopted by a vote of 30 in favor, 13 against, and 3 abstentions (UN Digital Library, July 7, 2017) |

| Promoting mutually beneficial cooperation in the field of human Rights A/HRC/RES/27/23 | March 2018, 37th | A/HRC/37/L.36 | Adopted by a vote of 28 in favor, 1 against and 17 abstentions (OHCHR, March 23, 2018) |

| The contribution of development to the enjoyment of human rights A/HRC/RES/41/19 | July 12, 2019, 41st | A/HRC/41/L.17/Rev. 1 | Adopted by a vote of 33 in favor, 13 against, and 0 abstentions (UN Digital Library, July 17, 2019) |

| Promoting mutually beneficial cooperation in the field of human rights A/RES/43/21 | June 22, 2020, 43rd | A/HRC/43/L.31/Rev.1 | Adopted by a vote of 23 in favor, 16 against, and 8 abstentions (UN Digital Library, July 2, 2020) |

| People-centered approaches in promoting and protecting human rights | October 7, 2020, 45th | A/HRC/45/L.49 | Withdrawn |

| Promoting mutually beneficial cooperation in the field of human rights | March 23, 2021, 46th | A/HRC/46/L.22 | Adopted by a vote of 26 in favor, 15 against, and 6 abstentions (OHCHR, undated) |

| The contribution of development to the enjoyment of all human rights | July 2021, 47th | A/RES/47/11 | Adopted by a vote of 31 in favor, 14 against, and 2 abstentions (UN Digital Library, July 27, 2021) |

| Legacies of Colonialism | September 2021 | A/HRC/48/L.8 | Adopted by vote 27 in favor, 20 abstaining (UN, October 8, 2021) |

| Realizing a better life for everyone | October 8, 2021, 48th | A/HRC/48/L.14 | Withdrawn |

| The contribution of development to the enjoyment of human rights | July 14, 2023 | A/RES/53/28 | Adopted by a vote of 30 in favor, 12 against, and 5 abstentions (UN Digital Library, July 18, 2023) |

| The Contribution of Development to the Enjoyment of all Human Rights | July 8, 2025 | A/HRC/RES/59/19 | Adopted without vote (UN Digital Library, July 16, 2025) |

| Promoting and protecting economic, social and cultural rights within the context of addressing inequalities | October 6, 2025 | A/HRC/60/L.27/Rev.1 | Adopted without vote (OHCHR, undated) |

Notes

[1] The Party’s preferred English translation of “人类命运共同体” is “community with a shared future for mankind.”

[2] Promoting and protecting economic, social and cultural rights within the context of addressing inequalities (A/HRC/60/L.27/Rev.1)

[3] Inboden, Rana Siu. China and the International Human Rights Regime. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.