China Assuming New Dominance in Turkmenistan

China Assuming New Dominance in Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan’s longstanding neutrality has kept it out of Russian regional security arrangements like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), which has constrained the level of influence Moscow could have in this notoriously insular Central Asian republic. But now, China is on the way to becoming the dominant outside power in Turkmenistan. The reasons for this rise in Beijing’s sway are manifold. First has been China’s already heavy involvement in Turkmenistan’s natural gas sector and transit routes through that country between China and Europe. But other factors include the rapidly growing Taliban threat to the Central Asian region (see EDM, July 13); the readiness of Ashgabat to support China on Xinjiang because, unlike other Central Asian countries, it lacks a diaspora being victimized there; and Beijing’s increasingly obvious interest in expanding its economic involvement in the region into security cooperation (see EDM, July 20). In doing so, Beijing has stolen a march on Moscow and positioned itself to compete with Turkey and other outside powers there in ways that it was never able to before.

Of course, an additional reason exists for China’s success in Turkmenistan: Its elites are among the most corrupt in the region, and Beijing has been using bribes to win the support of leaders there and in neighboring countries for some time. Moreover, because Turkmenistan is so closed off from the rest of the world—rightly or wrongly, it has been likened to North Korea in this respect—Chinese officials and Chinese firms have found it that much easier to gain the support of Turkmenistani officials than of authorities elsewhere (Carnegie.ru, January 22). Yet precisely because this situation is not discussed openly, it is impossible to tell just how large a role that element of Chinese diplomacy is in Ashgabat’s rapprochement with Beijing.

In any case, all of the above-mentioned factors have come together over the last month with a video conference between Chinese and Turkmenistani officials about security issues, a vote at the United Nations about Beijing’s role in Xinjiang and elsewhere, and, most important, a visit by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi to Ashgabat, where he met with Turkmenistan’s President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow. The first of these, on June 25, set the stage for what followed. Officials from Turkmenistan and China discussed how to respond to the emerging Taliban threat from Afghanistan and how Beijing could help Ashgabat defend itself, including via the use of private military companies it has already been deploying to protect Chinese-constructed and owned infrastructure in Turkmenistan (see EDM, March 25, July 20; Turkmenportal.com, June 25).

That meeting was followed by another Turkmenistani move important to the Chinese side. On July 14, Ashgabat’s representatives spoke at the 47th session of the UN Human Rights Council in support of Beijing’s position on Xinjiang and Hong Kong, arguing that outsiders must not interfere in the domestic affairs of other countries. (Turkmenistan does not recognize Taiwanese independence either.) That is music to Chinese ears, even as it puts Turkmenistan at odds with other Central Asian countries whose governments may cooperate with Beijing on economic projects but whose populations are often hostile to China because of its repressive moves against their co-ethnics in Xinjiang, thus limiting Chinese influence (Ritmeurasia.org, December 7, 2018; Turkmen.news, Azathabar.com, July 16, 2021; see EDM, November 21, 2019 and July 26, 2021).

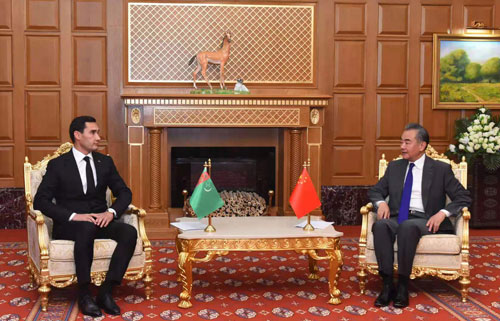

But confirmation of China’s new role in Turkmenistan came with Wang Yi’s trip to Ashgabat. The agenda of the visit, which reportedly was planned some time ago, quickly shifted from economic issues to security arrangements. Turkmenistan and China are already closely tied by developments in the gas and pipeline industry, and these links will only grow because of new deals signed between the two governments and because of the upbeat language both sides adopted about their future level of cooperation (Russian.news.cn, July 14; Tdh.gov.tm [1] [2], July 16; Hronikatm.com, July 17).

But if all that was expected, other moves during Chinese Foreign Minister Wang’s visit were not. A fundamental change is apparently occurring in the longstanding division of labor between Russia and China in Central Asia, where Russia had heretofore provided security while China offered investment. And this shift suggests China is now becoming the paramount outside power in Turkmenistan. The trend reflects a convergence of interests between the two. From Turkmenistan’s standpoint, because Ashgabat is not in the SCO or CSTO, it cannot count on Moscow for its defense; and now, facing a developing threat from the Afghan Taliban, it is interested in securing the backing of another country. Whereas from China’s side, it does not want to risk its already heavy economic investment in Turkmenistan but also seems to desire to play the role of a dominant outside power; thus, Beijing is more than happy to meet Ashgabat more than half way.

Berdymukhamedow received Wang warmly, and it is clear from news reports that the two discussed security arrangements—both “traditional” and “non-traditional,” in Wang’s words. The latter category almost certainly referred to the expanded deployment of “private” Chinese security company personnel to Turkmenistan, which was also referenced by lower-ranking Turkmenistani officials with whom the Chinese foreign minister spoke (Azathabar.com, July 20; Arzuw.news, July 13, 21).

This Chinese advance has major consequences for Central Asia and for other outside players. Regionally, it will deepen the divide between Turkmenistan and the other four former Soviet “stans” because Ashgabat will increasingly be looking to China rather than Russia for security, while the others will continue to look to Moscow. And for the outside powers, it will have a major impact as well. For Turkey, it will limit Ankara’s ability to promote a pan-Turkic or Neo-Ottoman agenda (see EDM, March 5, 2020 and April 1, 2021) by limiting Ashgabat’s willingness to cooperate. For Russia, it will reduce still further Moscow’s influence in Turkmenistan and show other Central Asian countries that there is an alternative to remaining within a Russian sphere of influence. And for the West, it will represent yet another Chinese challenge that neither Western countries nor Russia are in good position to counter—providing further confirmation of China’s rise as a military as well as economic power.