Competition Among Transportation Corridors in South Caucasus Heating Up

Competition Among Transportation Corridors in South Caucasus Heating Up

Moscow’s call to reopen the transportation corridors in the South Caucasus that have been blocked for 25 years because of the Armenian-Azerbaijani war over Nagorno-Karabakh has sparked new tensions between those two countries and new concerns by others. They concern the way in which the reopening of those corridors, should they in fact happen, will change the geopolitics of the region. But those tensions and concerns are only the tip of a much larger iceberg of geoeconomic and geopolitical problems: growing competition among the countries of the region and outside powers like Russia, China and Turkey over other transportation corridors in the South Caucasus. As a result, and in both cases, projects intended to tie the countries of the region closer together and to the broader world may lead to new conflicts. Some countries view such corridors as more of a threat to their current situation than a solution to their problems.

Indeed, the situation has already become so dire that the Moscow Institute for Political and Economic Strategy (RUSSTRAT) says in a new report that “a battle of transportation and communication corridors in the Trans-Caucasus” is already going on and is set to expand in the coming years (Russtrat.ru, June 6). This is not only because of the unresolved ethnic, religious, and political problems for each of the numerous projects now being pursued or talked about in the region but also because all the outside players have an interest in seeing some go forward and others fail because they view these transportation corridors as part of a larger geopolitical struggle. Consequently, the Moscow analytic center says, the chances for military conflicts in the region instead of receding will likely grow over the next decade or two, with the primary contest being between Russia and China, on the one hand, and the United States and Turkey, on the other, although both of these alliances will include others in particular cases and may also split because of conflicting national interests among leading members.

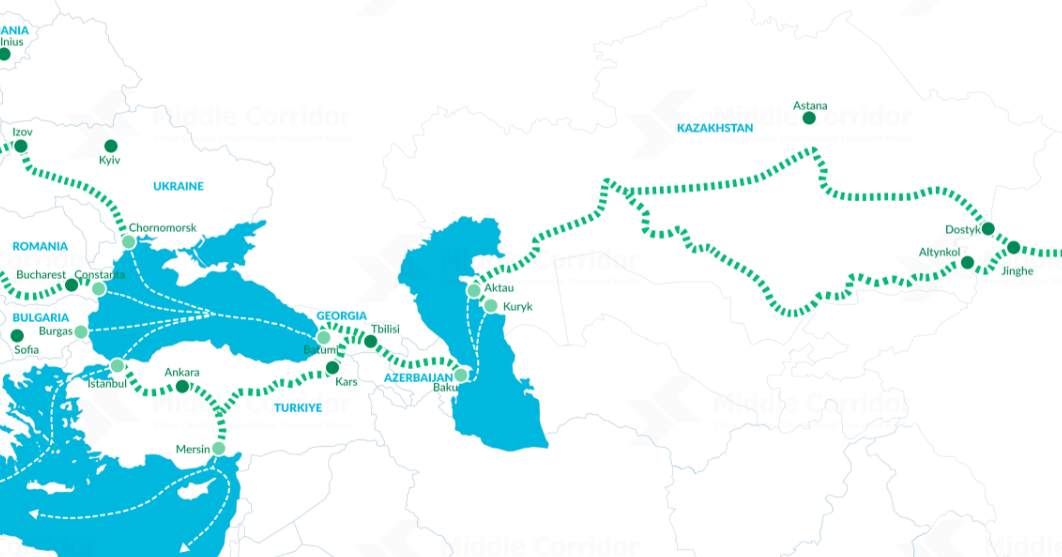

The number of international transportation corridors in the South Caucasus either functioning or under discussion is far larger than many assume. Some of the most prominent, RUSSTRAT says, include the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars route, China’s “One Belt, One Road” initiative, which consists of a variety of trans-Caspian and trans-Caucasus corridors, the unfreezing of corridors blocked by the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict, the construction of new canals between the Caspian and the Black Sea as well as between the Caspian and the Persian Gulf, the Lapis Lazuli corridor linking Afghanistan to Europe, and TRACECA between Central Asia and the Caucasus and Europe. Some of these routes were explicitly designed to bypass Russia, while others were planned to involve it more deeply. Moscow thus faces the task of challenging those that undermine its position while promoting those that help it make the Southern Caucasus both an east-west and a north-south hub and to do so over the objections of the US and some European states (On that challenge, see EDM, March 24, 2020).

Two things make the issue of transportation corridors in the South Caucasus especially important. On the one hand, whether and how they are resolved is likely to affect broader political arrangements for some time to come. Thus, outside parties, including Russia, China, Iran, Turkey, and the US, are interested in becoming involved far earlier than might otherwise be the case, lest others steal a march on them. But at the same time, RUSSTRAT says, it is a mistake to assume that economic transportation corridors by themselves will determine these relations. It is entirely possible for Russia and other countries to imagine a situation in which they will support or at least not oppose these corridors and simultaneously use other means to develop political and security cooperation. That is especially true for Russia, which has limited financial resources and whose “main ‘Caucasus’ interest now is not so much about corridors as about general political ties” that can be used to block the destabilization of the region, but it may also matter to China, the US, Turkey and Iran which have much greater resources in that regard, and which may have different interests as far as destabilization is concerned, the Moscow analytic center says.

What happens with these corridors will also determine what happens in other east-west and north-south routes. If the south Caucasus becomes a significant east-west route, it will reduce the Suez Canal’s importance and the North Sea Routes as transportation corridors. If it becomes a major north-south one, it may lead to the formation of an alliance between Russia and Iran that will block the spread of Turkish and Western influence in the Caucasus and greater Central Asia.

“History shows,” RUSTRAT analysts says, “that when the space of this region is under the control of a single geopolitical player, the risk of conflicts is minimized. The reverse is also true.” The USSR was able to keep the region stable, but Russia is not yet in a position to restore that kind of dominance over the South Caucasus. Other players are thus going to be increasingly important, and that means there will be conflicts. And these conflicts, the Moscow analysts continue, are most likely to break out precisely along the transportation corridors. Indeed, they have already started (See EDM, December 3, 2020 and March 3, 2020). The fact that analysts in Moscow are making this point suggests that other governments need to be prepared for precisely this kind of outcome not only in the case of the Armenian-Azerbaijani issue narrowly defined but across the entire Caucasus and even beyond.