Coronavirus Pandemic Provides Surprising Momentum to Trans-Eurasian Rail Transportation

Coronavirus Pandemic Provides Surprising Momentum to Trans-Eurasian Rail Transportation

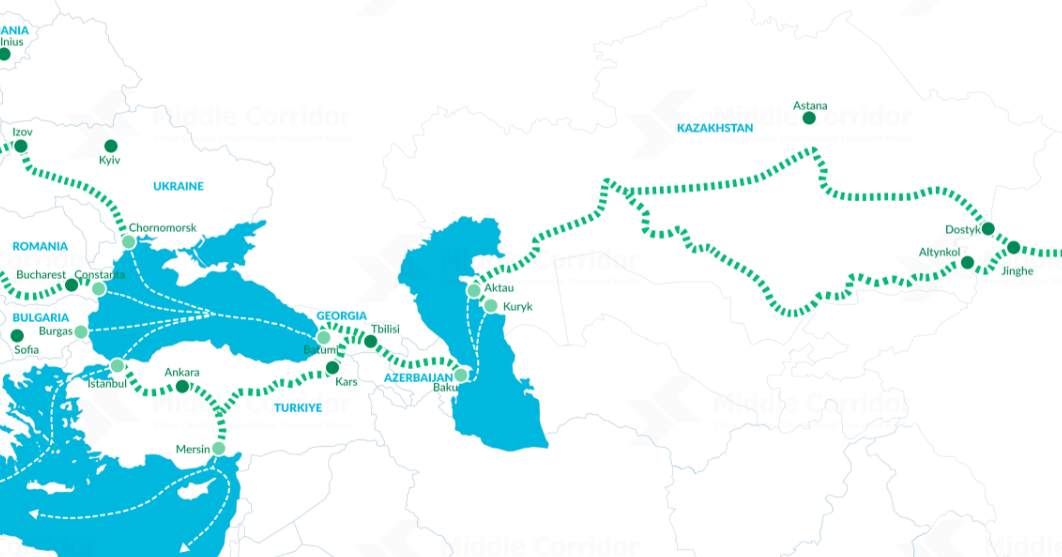

The COVID-19 pandemic generated many challenges for trans-Eurasian transportation corridors as borders were shut down, factories closed, and supply chains thrown into disarray. The disease outbreak and subsequent quarantine conditions did, however, offer new opportunities to railway container transportation along the Trans-Caspian route, also known as the Middle Corridor. In particular, railroads gained new prominence because they permit the movement of large quantities of goods while requiring little human interaction (Daily Sabah, May 5). Unlike trucks, trains can carry up to one hundred containers and only need a few crew members to cross borders. During the height of the pandemic, many countries closed their borders to road transit or adopted extra security and sanitary measures. For example, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan allowed only their own citizens to drive trucks inside their territory, while Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan required truck drivers to present negative coronavirus certificates or be tested at border crossings (Gzi.si, May 29).

The early spread of COVID-19 in Iran, the single most important gateway for Turkish exports to Central Asia, led to the closure of both the Iranian-Turkish and Iranian-Turkmenistani borders as early as late February–early March, forcing many of Turkey’s exporters to redirect their shipments toward the Trans-Caspian route (TASS, February 23; Daily Sabah, March 4; Report.az, April 18; see EDM, April 27). Moreover, many cargo flights were suspended, seriously crippling air freight capacity between China and Europe, in many cases raising the costs of the affected goods by two- or three-fold. This further boosted the level of interest in rail transportation—the closest viable replacement for air freight in terms of speed, even though trans-Eurasian cargo trains still take approximately one week longer to travel from China to Europe compared to shipping by air (Turkey Sea News, May 3).

Not surprisingly, since the early border closures to road traffic and curtailments to air freight, railway transportation along the Middle Corridor underwent a number of key developments. As instructed by the Turkic Council leaders after their April 10 meeting, the transportation ministers of the organization’s member countries met on April 30 to discuss how to facilitate the smooth transit of goods along this rail route (Mincom.gov.az, April 30). Turkish Transportation and Infrastructure Minister Adil Karaismailoğlu noted in mid-May that his country established a new railway container transfer system at the Canbaz Station, on the Turkish-Georgian border, which provides additional cargo capacity of 3,500 tons per day (Daily Sabah, May 13). The longest train in the history of the Middle Corridor—a 940-meter train with 82 containers—carrying products destined for Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, departed from the Turkish city of Kars toward Georgia on April 18 (Report.az, April 18). Two days earlier, Kazakh Railways announced the establishment of a Xi’an (China)–İzmit (Turkey) cargo express route along the Middle Corridor, which takes 16 days (Inbusiness.kz, April 16). A freight train consisting of 30 wagons and 60 containers departed Bilecik (near Istanbul) on April 30 and traveled 5,500 kilometers to its final destination in Bishkek, thus marking the establishment of a regular Turkey–Kyrgyzstan railway route (Zakonkz.net, May 26). The first test train, carrying three containers, ran this distance in three months; whereas this most recent train took only two weeks. Finally, during the April 30 Turkish Council transportation ministerial meeting, Uzbekistan offered to launch a joint-use Tashkent–Karakalpakia–Aktau–Baku–Tbilisi–Kars–Istanbul multimodal transport corridor (Mincom.gov.az, April 30).

Not surprisingly, amidst the global pandemic, rail transportation along the Middle Corridor experienced positive quarterly growth. At the April 30 meeting, Azerbaijani Transport Minister Ramin Guluzade noted that in the first quarter of 2020, transit cargo transportation via Azerbaijan increased by 32 percent compared to the same period last year (Mincom.gov.az, April 30). Moreover, according to Turkish officials, between March and May 2020, about 140,000 tons of goods were transported via the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars (BTK) Railroad, a key segment of the Middle Corridor. This was a three-month record for the BTK railway since its launch in 2017 (Apa.az, June 17).

Another key advance in building up east-west trans-Eurasian transport corridors this year was the launch of the China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan road/railway route (see EDM, July 6). On June 5, the three countries ceremonially sent the first train, carrying 25 containers from Lanzhou in central China to Tashkent, Uzbekistan, a distance of 4,400 kilometers (RFE/RL, June 29). This first trip took ten days, while subsequent shipments are expected to be completed in a single week. The route is 295 kilometers shorter than the existing rail link between China and Uzbekistan via Kazakhstan. According to Uzbekistani officials, it saves 5 days and costs 20 percent less (Chinalogist.ru, June 5).

The biggest shortcoming of this route is the missing 500-kilometer segment of railway between Kashgar, China, and Osh, Kyrgyzstan, where containers have to be moved onto trucks. Construction of a railroad linking these two cities has repeatedly been discussed at various levels over the past 25 years. In 2015, China offered a loan to Kyrgyzstan to cover the cost of its construction, which is estimated to be $5 billion–$6 billion (The Diplomat, June 22).

Under the leadership of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, Uzbekistan has been prioritizing relations with its regional neighbors and has also been actively lobbying for the project. However, while repeatedly declaring its readiness to participate in the project, Kyrgyzstan has been cautious on moving forward, despite the clear economic benefits it could expect, including transit fees.

First, the enormous financial cost of the project would place an additional debt burden on the country. Currently, the Kyrgyz Republic’s foreign public debt stands at $1.7 billion, 45 percent of which is owed to the Export-Import Bank of China (XinhuaNet, September 9, 2019). Receiving another $5 billion–$6 billion from Beijing would increase the country’s foreign public debt by 158 percent. Moreover, Kyrgyzstan’s population already demonstrates rising discontent over Chinese economic expansion into their country. The widespread perception among Kyrgyzstanis is that they are about to be taken over by their giant eastern neighbor.

Second, Beijing has routinely brought in Chinese workers to work on infrastructure projects in Central Asia financed by China. Kyrgyzstani public sentiment is uneasy about the number of such workers in the country. The small Central Asian republic periodically witnesses demonstrations against these foreign laborers, some turning violent and resulting in attacks on Chinese nationals (EurasiaNet, August 7, 2019). Under such conditions, hosting large numbers of additional Chinese workers would threaten to exacerbate public dissatisfaction against the government in Bishkek.