Corralling the People’s Armed Police: Centralizing Control to Reflect Centralized Budgets

Corralling the People’s Armed Police: Centralizing Control to Reflect Centralized Budgets

On March 21, the Chinese government announced a major restructuring of the People’s Armed Police (PAP) that will relegate all but one of its current units to other ministries, meaning that these units’ staff will no longer be part of the military service (National Audit Office, March 21). This came on the heels of another important change in December 2017, when command over the PAP, which had been shared between the Central Military and the State Council, was assigned exclusively to the former (South China Morning Post, December 28, 2017).

Both changes are expressly designed to disentangle civilian and military affairs and are set to solidly enshrine central government control over this crucial domestic security force (Global Times, March 21). Generally, the ability of local authorities to utilize PAP forces for their own purposes, including breaking up popular protests against corrupt officials by firing into crowds, has long been a concern for the central government (China Brief, June 19, 2008). Beijing’s fears of local power abuses involving the PAP were likely heightened in 2012 when former Chongqing Party chief Bo Xilai deployed the PAP against his police chief Wang Lijun. If regional power holders were ever to directly challenge the central government, the potential ability to control both PAP and public security forces would pose a severe threat.

This article demonstrates, through a close analysis of PRC domestic security spending, that the recent PAP reforms have sought to align unit command structures with existing spending distribution patterns. Put differently, central control of the PAP will now better reflect the central government’s control of the PAP’s budget. However, for restive minority regions where PAP forces closely interact with other security forces and where different PAP units jointly respond to security incidents, the implications of the intended simplification of military and civilian security structures are far from clear. While the planned changes will enforce strong vertical control, they may make more difficult the horizontal interactions between different security forces needed to address local developments.

Additionally, the analysis reveals how central-local PAP spending distribution patterns cause significant subsidization effects especially for restive minority regions such as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). The implication is that actual domestic security expenditures in Xinjiang and elsewhere are substantially larger than their already very high regional domestic security budgets (China Brief, March 12).

Domestic Security Budget Sub-Categories

Since its bloody involvement in the Tiananmen crackdown in 1989, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has been reluctant to act as an enforcer of domestic stability. This role was instead relegated to the PAP. In terms of equipment and strike capability, the PAP with its armored personnel carriers is equivalent to light infantry, placing it between the more heavily armed PLA and the regular police forces.

The PAP remains a secretive entity. Extremely little has been published on its budgets, let alone on spending distributions between its internal units or different regional levels. Shambaugh even argued that PAP expenditures are not included in domestic security budgets, and are therefore unknown [1]. However, PAP expenses are consistently listed (although not always disclosed) in these budgets.

Domestic security budgets on all regional levels typically contain the following sub-categories: People’s Armed Police (PAP, 武装警察), the public security organs (公安机关) which are administered by the Ministry of Public Security (国家公安部), the court system (法院系统), the judicial system (司法系统) which includes the prison system (监狱系统), the prosecutorial system (检察院系统), state security (国家安全) which is administered by the Ministry of State Security (MSS; 国家安全部), and the expenditures of the National Administration for the Protection of State Secrets (NAPSS; 国家保密局), the Chinese equivalent of the American National security Agency (NSA).

National Domestic Security Spending by Budget Sub-Category

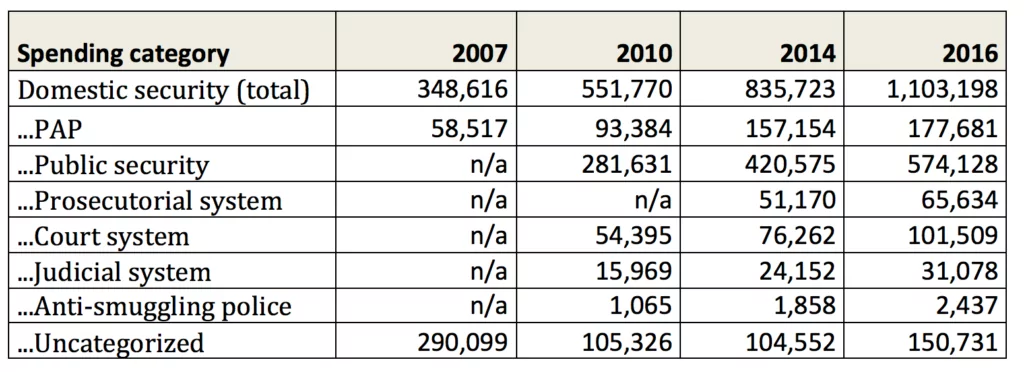

Prior to 2010, PAP expenditures were the only disclosed national domestic security budget sub-category. Since then, several other budget sub-categories have begun to be published (Table 1). Between 2010 and 2016, the spending shares of these sub-categories within total domestic security spending remained largely constant, with PAP and public security accounting for around 18 and 50 percent respectively.

Table 1. National domestic security spending in million RMB. Source: Ministry of Finance National General Public Budget Expenditure Tables (final accounts).

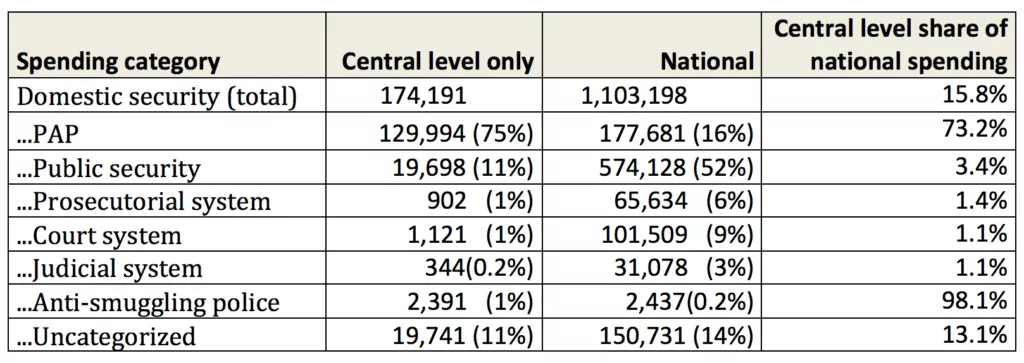

Within sub-categories, there are notable differences between central and regional level spending. Most PAP expenses (73.2 percent) are funded by the central government (Table 2). In contrast, public security and other domestic security related expenditures are mostly incurred at regional levels.

Table 2. 2016 Domestic security spending in million RMB. Source: Ministry of Finance, Local Government’s General Public Budget Expenditure (final accounts).

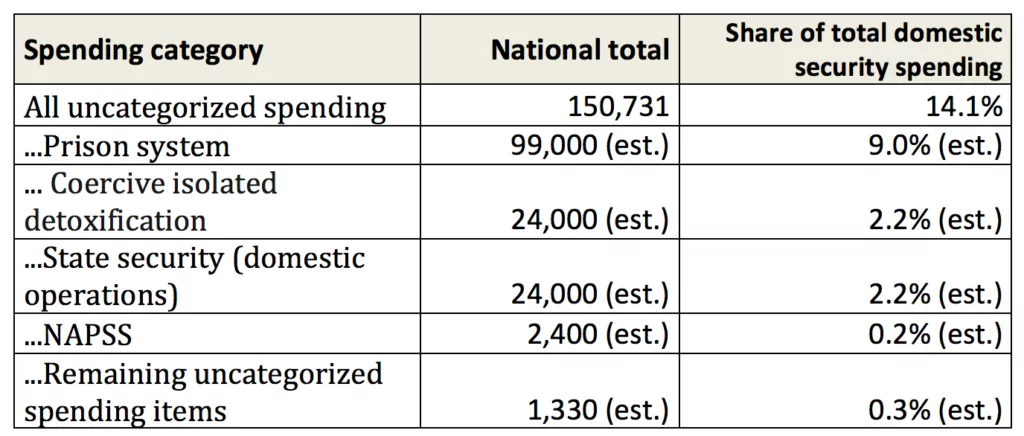

More detailed provincial spending breakdowns permit us to estimate likely national spending shares on uncategorized items (Table 3) [2]. The resulting figures leave little space for substantial hidden spending categories (compare also Table 4) [3]. Also, current public sector wage levels indicate that RMB 178 billion should be completely sufficient for the estimated 1.5 million PAP staff [4]. It is therefore likely that the disclosed PAP budget corresponds to the force’s actual spending.

Table 3. Estimated breakdown of uncategorized domestic security spending. Sources see [2].

Regional Domestic Security Spending Breakdowns

The breakdowns shown in Table 2 are available for provincial and regional budgets, with varying disclosure levels. Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) budgets exclude “classified items” such as domestic security, while Xinjiang even goes so far as to break down MSS and NAPSS expenditures (TAR government, 7 August 2017).

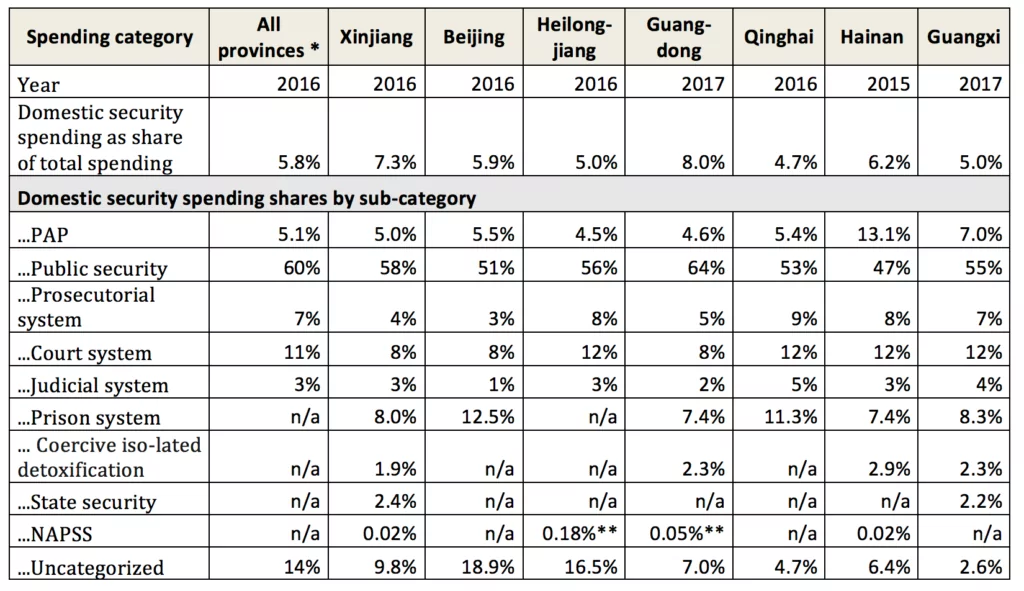

A comparison of several provinces and regions shows limited differentiation in regards to domestic security spending breakdowns (Table 4). PAP expenditure shares are likewise fairly stable [5]. Considering that the PAP plays a much larger role in restive minority regions such as Xinjiang or Qinghai, limited regional variation is likely explained by the fact that many PAP expenses are covered by the central government.

Table 4. 2016 domestic security actual spending shares for entire provinces or regions. Source: regional government finance departments (final accounts). * Excluding central government spending. ** Only provincial administrative level (省本级) figure (Guangdong data from 2015).

Spending Distribution Between People’s Armed Police Units

Prior to the most recent reform proposal, the PAP consisted of five major units. The most important and largest force are the Domestic Security Troops (DST; 内卫部队). Of an estimated 1.5 million troops, about 800,000 are thought to belong to the DST. [see 4] In the future, the PAP will only be composed of the DST, with the remaining troops, including those responsible for fire-fighting and border defense, transferred to the control of other ministries.

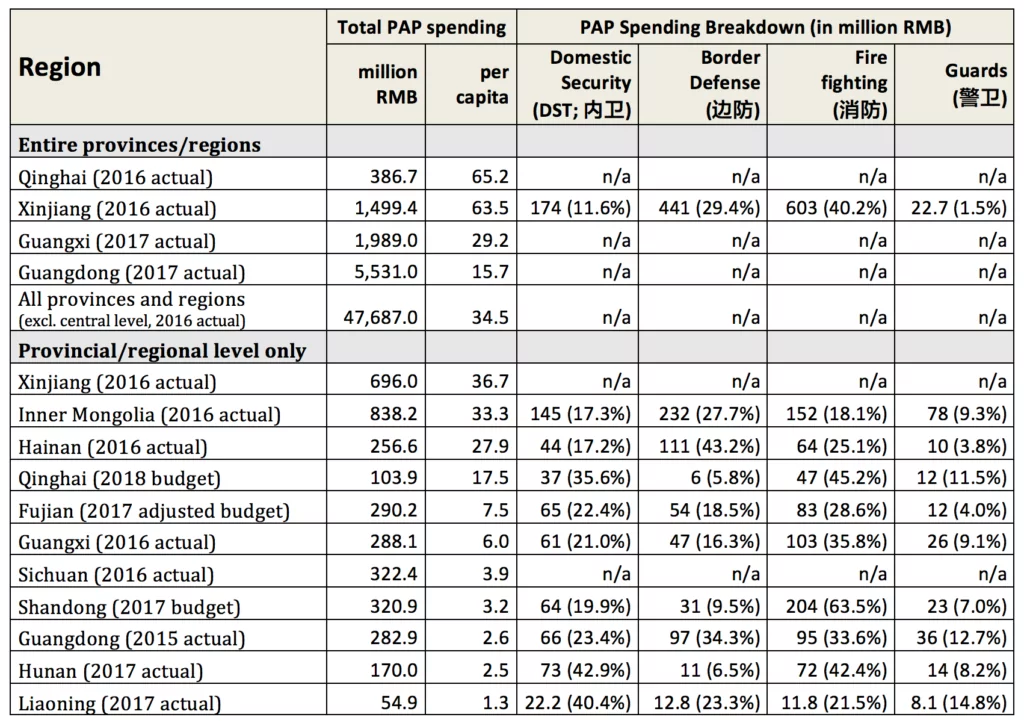

Per capita, Qinghai and Xinjiang spend twice as much on the PAP overall as the average of all provinces and regions (Table 5). Unfortunately, most PAP spending figures are only available for provincial or autonomous regional administrative, which excludes all sub-provincial spending and makes interprovincial comparisons more difficult (China Brief, March 12, figure 1).

Table 5. Domestic security PAP spending. Source: national and regional government finance departments.

Of great interest is that many regions provide PAP spending breakdowns in line with PAP unit divisions. They show that regional PAP spending tends to be dominated by fire fighting and border defense. While no such breakdowns are published for central government PAP spending, provincial and lower-level figures allow us to infer that the bulk of PAP DST spending is covered by Beijing, while regional spending focuses on the other units.

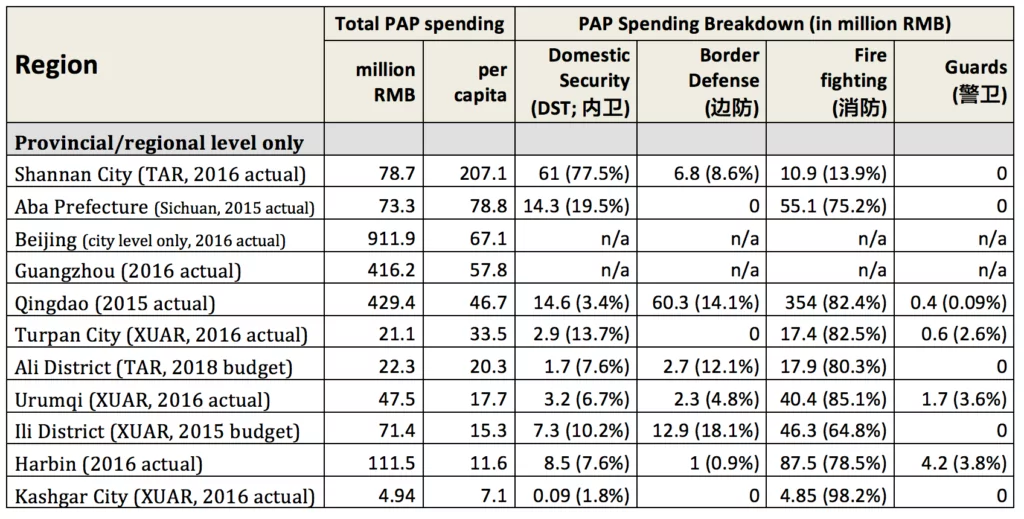

This is even more evident at sub-provincial or city levels (Table 6). Here, DST spending shares can be as low as single-digit even in highly restive minority regions. For example, Urumqi’s 2016 PAP expenditure was dominated by fire fighting (85 percent), with DST making up a paltry 6.7 percent. In Kashgar, a highly restive Uyghur majority city in China’s far west, 98.2 percent of PAP expenses that year were spent on fire fighting. Moreover, both of these cities’ total per capita PAP expenditures remained well below Beijing, Guangzhou and Qingdao [6]. Since southern Xinjiang is virtually blanketed by the PAP, these figures reveal the extent to which domestic security in such regions is funded by Beijing.

Table 6. Domestic security – PAP spending. Source: regional government finance departments.

Estimating Xinjiang’s Central-Local Security Spending Transfer Effect

In order to estimate central-local security spending transfer effects, we need to know Xinjiang’s PAP troop sizes. While there are no official figures, PAP numbers in 2008, prior to the 2009 Urumqi riots, were reported at approximately 70,000 (likely pertaining to the DST); an anecdotal account from 2013 cites a troop size of 200,000. [7] It is reasonable to assume that presently, Xinjiang’s DST alone number anywhere between 80,000 to 160,000.

If we estimate that about 80 percent of central government PAP expenses are spent on the DST (since other units are largely locally-funded), then it can be inferred that anywhere between 10 to 20 billion RMB of central level PAP funding in 2016 was spent on Xinjiang. The higher estimate roughly compares to the 17.5 billion RMB that the region spent on public security that year, and amounts to two-thirds of its entire domestic security spending (of 30.1 billion RMB). In contrast, Xinjiang’s own PAP expenditures that year only amounted to 1.5 billion RMB, up to half of which may have been on the DST. [8] If correct, then 93 to 96 percent of Xinjiang’s DST budget is funded by Beijing.

A comparison with public sector wage levels confirms the general accuracy of this rough approximation. If Xinjiang spent about half of its 2016 PAP budget (750 million RMB) on the DST, it could only pay the wages of about 7,000-7,500 staff. [9] Clearly, the region only sustains its troops with massive central funds. Similar estimates for the TAR are unfortunately precluded by a lack of information about its PAP troop size and budget.

Conclusions

Recent restructurings align PAP unit and command structures with spending distribution patterns. The vast majority of PAP domestic security troops (DST) are funded by Beijing, while other units along with public security forces are largely locally-funded. When the PAP is reduced to the DST (and the coast guard), then both the command and nearly all PAP budget control will firmly rest with the central government.

The potential consequences of increasing central control for local stability maintenance dynamics are significant. Without access to PAP command, local officials may have to rely more strongly on regular police forces for daily stability maintenance. In addition, all PAP units have to mobilize their forces in the case of domestic security incidents. The fact that PAP units with significant local funding shares such as fire fighting will no longer be controlled by public security agencies renders such mobilizations more complicated.

The original rationale behind a mixed vertical and horizontal system of control was to permit a degree of local autonomy in line with local expertise and needs, while allowing the Party to retain ultimate control (China Brief, March 24, 2016). With the horizontal PAP command chains largely removed, it is questionable whether the CMC command chain lends itself to being involved in the complexities of daily security operations. In most regions, the PAP remains in the background, only called upon for emergencies. However, in restive minority regions such as Xinjiang or Tibet, it is heavily involved in daily policing tasks, with estimated expenditures in Xinjiang roughly corresponding to those of regular police forces. While the state is “disentangling” military and civilian domestic security regimes, security maintenance in these regions is actually predicated upon their constant interaction.

In this respect, the restructuring of the PAP exemplifies the same inherent contradictions as Xi Jinping’s wider structural reforms. By strengthening vertical mechanisms of control and punishment at the expense of horizontal coordination and cooperation, China’s new governance systems discourage local experimentation and adaptation, decreasing the effectiveness of local policy implementation (East Asia Forum, December 20, 2016). In restive regions, the proposed changes to the PAP could have a similarly problematic effect on stability maintenance management.

Adrian Zenz is researcher and PhD supervisor at the European School of Culture and Theology, Korntal, Germany. His research focus is on China’s ethnic policy and public recruitment in Tibet and Xinjiang. He is author of “Tibetanness under Threat” and co-edited “Mapping Amdo: Dynamics of Change”.

Notes

[1] Shambaugh, David, “China Goes Global” (2013, p.328, note 15). Conversely, see Wang, Shaoguang, “China’s Expenditure for the People’s Armed Police and Militia” (2003, Chinese University of Hong Kong). This article’s author’s research further indicates (contrary to Shambaugh) that state security expenses (for domestic operations) are likewise included in domestic security. [2] See Table 4 for details and sources. Spending estimates for state security were based on a population-weighted sample (2016 population figures) from provincial (regional) administrative level budgets for (m stands for million RMB): Xinjiang (2016 actual, 696m), Qinghai (2018 budget, 180m), Guangdong (2015 actual, 1,348m incl. Guangzhou and Shenzhen), Liaoning (2017 actual, 250m), Fujian (2016 actual, 397m), Guangxi (2016 actual, 356m), Inner Mongolia (2017 budget, 330m), Hainan (2016 actual, 188m), Hunan (2017 actual, 696m). Due to their unique security situation, Xinjiang and Qinghai were only weighted at 40 percent in order to prevent them from skewing the sample. This results in an estimated average national state security spending figure of 15.4 billion RMB. While for some regions such as Xinjiang and Guangxi, nearly all state security spending occurs at the regional administrative level, cities in Guangdong had substantial related spending figures of their own. Consequently, the national average has to be adjusted by an unknown margin. In order to account for this as well as an unknown amount of central government state security spending, it was decided to set the state security spending share within domestic security at 2,2 percent (comparable with related shares for Xinjiang and Guangxi). This results in the 24 billion RMB estimate (or 17,35 RMB per capita). Notably, Xinjiang and Qinghai’s per capita state security spending is nearly twice as high as the national average (30.6 and 30.4 respectively). [3] For example, Heilongjiang, which did not publish separate figures for prison system, coercive isolated detoxification or state security in its 2016 accounts, featured a large (16.5 percent) share of uncategorized domestic security spending – comparable to the national share. In contrast, regions that provided comprehensive breakdowns had small percentages of uncategorized expenses (Table 4). Only Xinjiang and Beijing had substantial uncategorized items remaining, but these are unique regions with particularly intense securitization regimes. [4] Troop size estimates: Blasko, Dennis, “The Chinese Army Today: Tradition and Transformation for the 21st Century” (2006, p.23); CGTN (December 31, 2017); Chinese Wikipedia. No statistics are available on average annual PAP human resource expenses. At the 2016 average annual public sector wage of 67,569 RMB, the average annual cost of a PAP member to the state (including employer expenses and various subsidies) can be roughly estimated at 80,000 RB (source: National Bureau of Statistics). If 70 percent of the national PAP budget was spent on wages and related costs, the state could support 1.55 million PAP troops. In this, the PAP benefits from the fact that many (if not most) of its research and development expenses are likely paid out of the military budget. [5] While Hainan’s 2015 PAP expenditure share was unusually high, it was likely a spike. On the provincial administrative level, the provinces’ PAP expenditures in 2015 were 50 percent higher than in 2016 and 130 percent higher than the 2017 PAP budget. [6] In the TAR, regional differences in per capita PAP spending and related distributions are much greater. However, since the TAR’s administrative-level PAP figures are not disclosed, interpretations of its sub-regional spending data are problematic. It is however likely that in these remote and mountainous regions, the state is particularly relying on PAP forces for domestic security. [7] BBC (July 7, 2013), Tiexue.net BBS (user post from December 25, 2017). [8] In 2016, Xinjiang spent 1,499.4 million RMB on the PAP, of which 856.6 million was borne by the regional administrative level. Sub-regional budgets indicate that local DST spending shares are unlikely to exceed 15 percent. Even if 75 percent of administrative level PAP expenses fell on the DST, which is actually quite likely, Xinjiang’s overall DST spending share would not exceed 50 percent (or 750 million RMB). Sources: regional finance department. [9] Estimated based on Xinjiang’s annual average public sector wage of 63,739 RMB, with an added 20 percent for an estimated annual average PAP staff cost of about 76,500 RMB (source: National Bureau of Statistics). Since average per capita PAP human resource expenses are not published, this is only a rough approximation.