Iran Rapidly Expanding Rail Links With Central Asia and Caucasus

Iran Rapidly Expanding Rail Links With Central Asia and Caucasus

The United States and other Western countries have worked long and hard to marginalize Iran as punishment for its transgressions on the international stage. Nevertheless, Iran’s neighbors as well as states further out, including Russia, China and the Central Asian republics, understand that their plans to establish strategically important north-south and east-west regional transportation routes will depend on the development of Iranian railways and the integration of its domestic rail system with bordering countries. Tehran and its supporters are also aware of that fact, and they are increasingly moving below the West’s radar to change the map of the region (see EDM, February 20). In that light, a series of new Iranian expert opinions is especially noteworthy.

Those aforementioned remarks by Iranian analysts were, in fact, prompted by the recent opening of a railway linking Haf, in northeastern Iran, to Herat, in western Afghanistan. According to several Tehran-based scholars, that development opens up new “strategic prospects” for Iran far beyond only Afghanistan. Indeed, they insist, the new railway “is one of the most important national and international projects, which not only increases the economic and transportation ties between Iran and Afghanistan but also increases stability and security, creates possibilities for job creation, and improves the economic situation of the entire region.” Some even suggest the rail link can eventually enable the rise of a new, Iranian-led cultural community in this part of the world (IRNA, December 10).

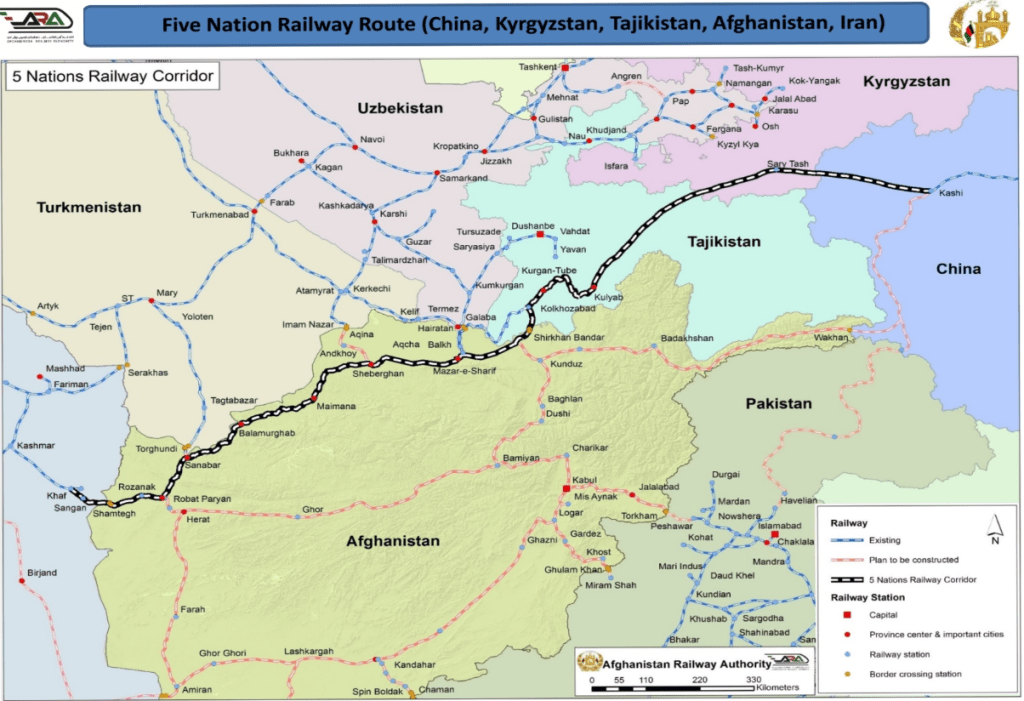

“The Haf–Herat line revives the Silk Road as far as railways are concerned and unites the Chinese railroad with Iran through Afghanistan,” declared analysts for Tehran’s government news agency IRNA. “The line, thus, plays an important role not only in the development of Afghanistan but also in the development of the railroad network for the transit of goods from Central Asia to the Indian Ocean, and it also marks the beginning of the creation of both the East-West and North-South international trade corridors” (IRNA, December 10).

Such seemingly bombastic claims by Iran’s news agency are backed up by a more scholarly analysis offered in a detailed, 5,000-word article by Erbrakhimbay Sadami, a specialist on transportation networks at the University of Tehran (Iess.ir, December 6; Casp-geo.ru, December 12). Sadami notes that this Iranian link will allow the land-locked countries of Central Asia to reach the broader world and do so on international-standard tracks with modern computer management. The connection to Iran will have the effect of reducing their integration with and dependence on the Russian-gauge railway system left over from Soviet times.

The Tehran scholar writes that the Haf–Herat line is only the first part of a larger effort to build railways in eastern Iran and to adjoining countries—projects the Islamic Republic sees as critical to its own economic development and national security as well as conducive to overcoming sanctions by integrating itself into the wider world. In this, he continues, Tehran hopes to work with Moscow, which also has an interest in reaching the Indian Ocean for trade, and with Beijing, as part of the latter’s “One Belt, One Road” vision of linking the Asia-Pacific and Europe. Russia and China have already invested in Iranian railway projects; and Sadami clearly expects them to do more, especially if Moscow and Beijing remain at odds with the West as well (Iess.ir, December 6; Casp-geo.ru, December 12).

Iran’s railway ambitions, however, are hardly exhausted by its moves into Afghanistan (including via Turkmenistan). Additionally, Tehran is continuing to work toward integrating Iranian railroads with railway networks in the South Caucasus. The latter goal, in particular, was given new impetus by the November 9 trilateral ceasefire accord, signed in Moscow, that ended the latest round of intense fighting in Karabakh between Armenia and Azerbaijan. But most importantly, from Iran’s perspective, the document unblocked undeveloped or abandoned regional transportation networks in the north-south as well as east-west directions (see EDM, December 3; News.day.az, November 23; Casp-geo.ru, December 7). Even before that happened, Iran sought to expand its rail network to the Caspian Sea port at Enzeli, to serve as an intermodal transportation hub along trade corridors connecting with Russia and the countries of the South Caucasus and Central Asia (IRNA, December 2, 2018; Casp-geo.ru, December 7, 2018).

Iran’s hopes for this network are enormous, but in both the east and the north, Tehran faces stiff competition from other players who may not want to see it succeed. In the east, as Sadami suggests, Pakistan has its own agenda and a long history of interest in building railways northward and westward. If Tehran does not finish its network, it may find Pakistan in a position to play the transit role Iran hoped to embody vis-à-vis Afghanistan, Central Asia and, possibly, China as well. And of course, it faces challenges in the north as well. Europe and the United States have long sought to promote the development of rail lines in the South Caucasus to bypass Iran and Russia; and now Turkey, with the opening of the Zengezur corridor (across southern Armenia), has announced plans to build a railway eastward to the border of Azerbaijani Nakhchivan and, ultimately, all the way to Baku (Anadolu Agency, RBC, November 12).

At a minimum, that puts Iran on a collision course with Turkey, its longstanding geopolitical enemy, as well as the West. In the current environment, the outcome of that competition may depend first and foremost on the construction of regional railways, which, for landlocked states, are typically the most important links to the outside world. If Iran remains at odds with the West, the West may back Turkey more heavily. Nonetheless, Tehran is demonstrating by its progress in building a cross-border railroad into Afghanistan that, even under sanctions, it is ready and able to act—at least as long as it secures support from Moscow and Beijing.