PLA Navy Shifts Training Focus from Near-Shore to Blue-Water Operations

PLA Navy Shifts Training Focus from Near-Shore to Blue-Water Operations

Executive Summary:

- In June 2025, the Liaoning and Shandong carrier strike groups conducted operations in the Western Pacific, achieving three major milestones with significant strategic implications for the U.S. military and Indo-Pacific regional states.

- The three key milestones include the first simultaneous deployment of two carrier strike groups beyond the First Island Chain; the first time a Chinese carrier has operated beyond the Second Island Chain; and a record-breaking duration for carrier operations outside the First Island Chain.

- These military actions were part of far-seas mobile operations training, conducted within the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s annual routine training program. This indicates that the Chinese Navy has begun to regularize far-seas mobile operations training, which may require the United States to adjust its force posture in the region.

- Together with the large-scale PLA military operations around Taiwan that have taken place since 2022, these developments suggest that the Central Military Commission likely assesses that the Chinese military possesses comprehensive near-seas combat capabilities, implying that the PLA Navy could believe it has secured operational dominance in nearby waters and may adopt more assertive actions against foreign naval vessels in these areas.

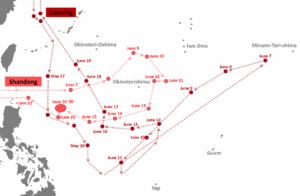

On May 27, the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s (PLAN) Liaoning aircraft carrier crossed the first island chain and entered the Western Pacific. On June 7, the Shandong carrier group followed suit, transiting from the South China Sea into the Philippine Sea. While in the Western Pacific, the carrier groups engaged in a round of far-sea realistic combat training (远海实战化训练) and adversarial drills (对抗演练). The drills included reconnaissance and early warning, counter-strike operations, anti-surface assaults, air defense, and round-the-clock tactical flights by carrier-based aircraft; achieving new milestones for the PLA Navy (PLA Daily, July 1). By June 22, both groups had returned to the East and South China Seas, respectively.

The drills constitute a shift in the PLAN’s focus toward long-range operations. This likely stems from an assessment by the PLA’s Central Military Commission (CMC) that the navy has achieved sufficient combat capability in the country’s near seas (近海). This is something that could have important implications for U.S. force posture in the region. The PLA has begun to cross the Second Island Chain, which includes Guam, in the Western Pacific. This shift brings Chinese forces closer to Hawaii. As a result, the United States may need to adjust its force deployments and rotation schedules accordingly. In addition, the latest shift could imply that the PLA Navy believes it has secured operational dominance in nearby waters. If so, it likely will engage in more assertive and potentially unsafe behavior during naval encounters with vessels from neighboring states in future.

Deployment Achieves Milestones for Scale, Range, and Duration

The PLA Navy achieved three milestones during this latest round of training drills.

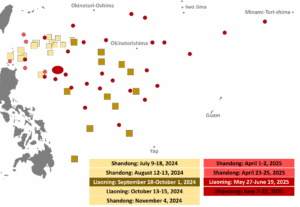

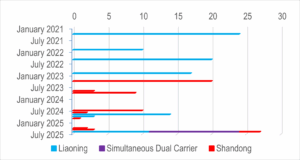

First, the drill marked the first time two PLA aircraft carriers had operated simultaneously in the Western Pacific, a deployment that lasted approximately 13 days. The Liaoning group conducted operations from May 27 to June 19, while the Shandong group operated from June 7 to June 22. This contrasted with previous instances of carrier groups crossing the first island chain into the Western Pacific. According to Japan’s Ministry of Defense, which publishes data going back to 2021, there have been 14 instances of Chinese carrier group deployments in the Western Pacific prior to the two aircraft carrier deployments this June. In each of those earlier cases, only a single carrier group operated in the region. The shortest interval between different Chinese carrier groups entering the Western Pacific had been about two weeks, when the Liaoning carrier group operated there from October 13–15, 2024, before the Shandong group entered the area on November 4, 2024. On that occasion, despite operating in proximate areas, they did not conduct operations simultaneously.

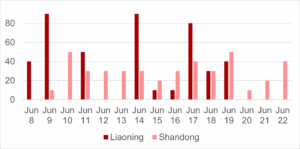

In the period June 14–18, the two carriers likely conducted carrier-versus-carrier training exercises. We can infer this from the fact that they maintained a distance of 500–600 kilometers for the duration of that period—beyond their outer defense zone boundary. (This boundary extends to about 400 kilometers, according to analysts at the China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI Notes, July 16, 2024)). The high number of sorties from the Liaoning carrier over those five days—90 on June 14 and 80 on June 17—also supports this thesis. These were the joint-highest and second-highest single-day sortie counts across the entire period (see Figures 1 & 2 below).

Figure 1: Area of Operations for the Liaoning and Shandong Carrier Strike Groups

(Source: Created by K. Tristan Tang based on Japan Ministry of Defense press releases)

Figure 2: Daily Sortie Counts of Carrier-Based Aircraft for Liaoning and Shandong

(Source: Created by K. Tristan Tang based on Japan Ministry of Defense press releases)

The operation also marks the first time Chinese aircraft carriers have sailed beyond the second island chain—a second milestone achievement. On June 7, the Liaoning carrier group operated approximately 300 kilometers southwest of Minami-Tori-shima. It then moved southwest about 400–500 kilometers on June 8, navigating waters between the second and third island chains. Previously, the farthest distance traveled by a Chinese carrier was in late December 2022, when the same carrier operated in the Philippine Sea about 870 kilometers south of Okinotorishima and roughly 700 kilometers west of Guam (see Figure 3). As in 2022, the Liaoning’s farthest distance from its homeport in Qingdao, Shandong, was about 3,000 kilometers; however, this time it came much closer to Midway Island than any previous excursion.

Figure 3: Closest Distances of Chinese Aircraft Carrier Deployments near Guam

(Source: Created by K. Tristan Tang based on Japan Ministry of Defense press releases)

The movements of the Liaoning likely indicate that it played the role of a “blue force,” simulating a U.S. carrier group, while the Shandong group possibly acted as a “red force” in adversarial exercises (Xinhua, July 1). Until June 7, the Liaoning carrier group advanced toward its easternmost point—roughly 3,000 kilometers from Midway Island. At this point, it turned around and proceeded west, just as the Shandong carrier group exited the first island chain into the Philippine Sea, sailing eastward. These were not necessarily tactical-level drills involving individual ships and aircraft but may have involved strategic-level maneuver tests of carrier group deployments in the Philippine Sea.

Compared to PLA carrier group operations conducted in 2024, those conducted in 2025 so far have taken place farther from the PRC. Among five carrier group deployments in 2024, four operated in a relatively concentrated area near the Bashi Channel, except for the batch at the end of September 2024 that showed a noticeably wider operational range. In contrast, the four carrier group deployments in 2025 displayed a clear pattern of dispersion, as illustrated in Figure 4 below. In another divergence from the Joint Sword 2024B exercise and the Strait Thunder 2025A drill—both of which involved carrier deployments—no carrier-based aircraft flew near Taiwan’s eastern coast during the latest drills, according to Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense (China Brief, November 1, 2024; April 11).

The third milestone achievement from the most recent deployment was the setting of a new record for the longest continuous duration of Chinese carrier groups conducting operations beyond the first island chain. For 27 consecutive days, at least one carrier group operated in the Western Pacific. The Liaoning group remained active for 24 days, matching its operational duration in April 2021, while the Shandong group operated for 16 days, the longest since its 20-day deployment in April 2023 (see Figure 5 below).

PRC officials have emphasized that this carrier activity is part of the PLA’s annual routine training program (根据年度计划组织的例行性训练), focusing on exploring formation combat elements and the practical application of combat power (PLA Daily, July 1). This indicates that the expanded operational range beyond the second island chain reflects a military-issued training plan aimed at exploring and validating training scenarios and maritime areas that were previously rarely addressed.

Figure 4: Comparison of Chinese Aircraft Carrier Deployments in the Western Pacific in 2024 and 2025

(Source: Created by K. Tristan Tang based on Japan Ministry of Defense press releases)

Figure 5: Number of Days of Chinese Aircraft Carrier Deployments Beyond the First Island Chain

(Source: Created by K. Tristan Tang based on Japan Ministry of Defense press releases)

Latest Training Drills Emphasize Far-Seas Mobile Operations

Two key implications emerge from the foregoing analysis of the PLAN’s latest drills. The first is that the PLA has started shifting the focus of its training from near-seas comprehensive operations (近海综合作战) toward far-seas mobile operations (远海机动作战). The second—which follows from the first—is that the CMC likely has determined that the PLA now possesses comprehensive near-seas combat capabilities (近海综合作战能力), such as those needed for operations around Taiwan.

Supporting evidence for the first implication—that the PRC has begun shifting its training focus to far-seas mobile operations—can be found in the 2020 edition of the Science of Military Strategy (战略学), published by the PLA. According to official definitions, near-seas comprehensive operations describe the integrated use of forces in near-sea areas for homeland defense, island and reef protection, convoy escort, and maritime raid operations through multi-branch coordination and multi-disciplinary support. It primarily includes the navy’s reconnaissance and early warning capabilities in near-seas areas, situational control, rapid response to emergencies, strike capabilities against enemy targets, self-defense abilities, and the effective deployment of support within the operational maritime area. Far-seas mobile operations, meanwhile, refer to maritime combat actions conducted in “oceanic waters far from land” (远离陆地的远海海域). These operations primarily aim to control key strategic passages, protect sea lines of communication, safeguard overseas interests, deter maritime military crises, and maintain global peace.

Conducting mobile operations far from the homeland poses unique challenges due to the lack of shore-based air support and close-range logistical supply. It requires that the navy concentrate its elite forces at sea to sustain “far-seas raiding and guerrilla warfare” (远海破袭游击作战), striving for speed and effectiveness. To achieve this, it must enhance battlefield early warning and monitoring capabilities, the collection, processing, and dissemination of information and data, decision-making and command functions at the command centers, coordination among fleet units, precise strike capabilities of main combat weapons, and self-defense abilities of mobile task forces.

Efforts to explore and train command decision-making capabilities and fleet coordination skills are clear in the PLAN’s approach to recent far-seas activities. This is true for both the recent dual carrier operations in the Western Pacific, which involved extensive fleet movements, multiple changes in fleet composition, and frequent carrier-based aircraft activities, as well as for the live-fire drills that took place in February in waters east of Australia, which included tests of precise strike capabilities for main combat weapons.

The second, equally important implication of the latest drills—that the shift to focusing on developing far-seas mobile operations indicates satisfaction that sufficient near-seas combat capability has been achieved—is also supported by doctrine. The Science of Military Strategy states that far-seas mobile operations build upon a foundation of near-seas comprehensive combat capability.

Since August 2022, the PLA has announced and conducted five large-scale military exercises and drills targeting Taiwan. The first, launched in response to Speaker Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, was officially categorized as a drill, with official statements emphasizing its training purpose and validation of operational scenarios. The subsequent three “Joint Sword” (联合利剑) exercises conducted in 2023 and 2024 built upon that initial drill, advancing into more complex military exercises. Unlike the multi-day military operations conducted in 2022 and 2023, the two exercises in 2024 lasted only two days and one day, respectively, yet still involved the deployment of a large number of aircraft and vessels. This aligns with the rapid response capabilities required for near-seas comprehensive combat operations. One possible reading of these drills is that, beyond political posturing, they may also have been motivated by a desire to expand maritime defense depth and enhance the ability to respond to external major threats, particularly from the United States (Xinhua, June 11; Global Times, June 17).

It is plausible that the Central Military Commission is satisfied with the outcomes of these previous drills. This could also explain why the Strait Thunder 2025A drill in April reverted to a less complex drill format (China Brief, April 11). Now, having increasingly normalized its military presence in its neighborhood, the PRC seeks to do the same in the Western Pacific. Ambitions to expand the reach of its military are evident in recent national security pronouncements, such as a white paper on national security released in May (China Brief, May 23, July 17). These indicate that the PLAN hopes eventually to establish an integrated maritime defense system that connects near and far seas and combines internal and external security—a direction for “maritime battlefield construction” (海上战场建设) that military strategists such as Liu Mingfu (刘明福) advocate (China Brief, July 3, 2024). [1]

Conclusion

The PLA Navy’s shift in training focus from near-seas to far-seas operations could lead to more direct pressure on the United States. Key U.S. military outposts beyond the mainland—such as Hawaii—could have to contend with increased naval presence by Chinese naval forces operating closer and with greater endurance than before. This development not only challenges the United States’s strategic depth in the Pacific but may also compel it to reconsider its force deployment and readiness posture throughout the Indo-Pacific region.

The views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the positions of the National Defense University, the Ministry of National Defense, or the government of ROC (Taiwan).

Notes

[1] 劉明福,《新時代中國強軍夢》(北京:中共中央黨校出版社,2020),頁264.