Vatican Agreement Latest Front in Xi’s Widening Religious Clampdown

Vatican Agreement Latest Front in Xi’s Widening Religious Clampdown

A new agreement between the PRC and the Vatican on the joint appointment of bishops demonstrates that the administration of CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping appears to have won a modicum of international approval for its domestic religious policy. The deal went forward despite substantial criticism of Pope Francis, based on the CCP’s abysmal—and worsening—track record in protecting freedom of belief. In recent years, Xi has doubled down on his policy of “Sinicizing” foreign religions such as Islam and Christianity, code for, rendering them compatible with core CCP values, including unreserved loyalty to the Party. The Sinicization campaign has resulted in campaigns of religious persecution, targeting both Muslims and Christians, of an intensity unheard of since the Cultural Revolution.

“They Will Suffer”

The provisional agreement between the Vatican and the Party—whose contents have remained under wraps—does not mean Beijing will improve its treatment of Catholics in both official and “underground” churches. (China’s estimated 12 million Catholics are divided between those who attend churches run by officially sanctioned, CCP-led Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association [CCPA], and those who remain underground. The latter insist on professing loyalty to the Holy See rather than the CCP; Radio Free Asia, September 24; South China Morning Post, September 22).

In a late September interview with media from around the world, Pope Francis acknowledged that affiliates of the unofficial church might be left worse off by the deal. “It’s true, they will suffer,” the pontiff said, referring to the plight of underground Catholics (Associated Press, September 26). While the pope insisted that the agreement would give the Vatican veto power over the appointment of bishops within the PRC, there is no guarantee that CCPA-affiliated or unauthorized churches would be spared the tight grip that the party-state apparatus exercises over both Catholics and Protestants. It is perhaps for this reason that Cardinal Joseph Zen of Hong Kong, a longtime critic of the Beijing regime, called the preliminary agreement “a betrayal.” “The Chinese government will succeed in eliminating the underground church with the help of the Vatican,” Zen said in Hong Kong (Ucanews, September 28; Apple Daily [Hong Kong], September 23).

It is possible that the “provisional agreement,” which the Pope characterized as “not political but pastoral,” will undergo further revision. It could also be a prelude for the Vatican to switch diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to the PRC. Regardless, it remains painfully obvious to the nation’s estimated 67 million Christians that the Xi administration has, in tandem with its stranglehold over ideology and propaganda, continued to tighten already-stringent control over Christianity in China [1]. Even many “official churches” have found little protection, despite their being directly under the supervision of the Communist Party’s ascendant United Front Department.

Since the spring, well-established Protestant house churches in big cities ranging from Beijing to Chengdu have been forcibly closed by police (Voanews.com; September 26; Christiantoday.com, September 10). A member of the Beijing-based Zion Church said that believers are no longer allowed to worship in premises they had used for years. Many worshippers were subject to interrogation by police—and threatened with harm to themselves and their family if they continued to attend services [2]. Since last year, both official and house churches have been forced to install 24-hour video surveillance systems connected to police computer systems. Many churches are now guarded day and night by police or members of neighborhood vigilante groups (Christiantoday.com, April 11, 2017; Premierchristianradio.com, April 3, 2017).

Putting “Sinicization” into Practice

The legal basis for this, the most severe suppression of religion since the Cultural Revolution, are the recently revised Regulations for Religious Affairs, which came into effect in early 2018. The regulations stipulate that worship and missionary activities must take place “in registered sites” approved by the police. Church organizations must secure “registration certificates for sites for religious activities” from the authorities. This amounted to a further blow to the legal status of house churches, exposing their personnel as never before to harassment and imprisonment. Churches have to accept regular “supervision and inspection” of their religious and accounting practices by government religious bodies. Financial and other contributions from overseas organizations are forbidden. Most significant is the stipulation that religious activities “must not endanger state security, damage social order … or hurt national interests.” Nor are religious organizations and individual believers allowed to “damage national unity, split up the nation or perpetrate terrorist activities” (Ucanews.com, February 8, 2018; Gov.cn, September 7, 2017).

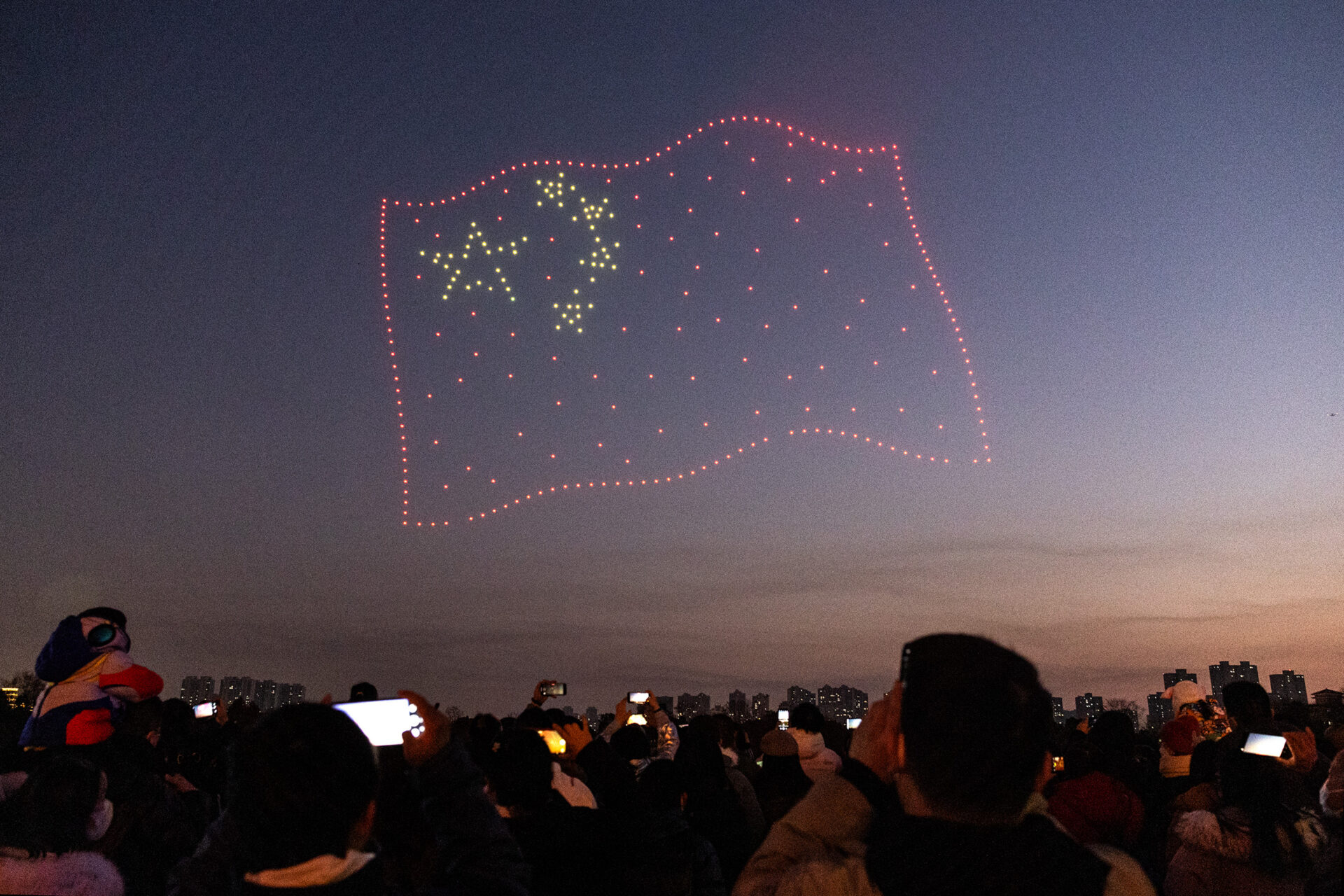

Xi’s plan for religion—and in particular Christianity—is “Sinicization” (中国化), a concept found in nowhere in the country’s statue books. The term implies that key Christian teachings of the church must be rendered compatible with “socialism with Chinese characteristics”, and that all churches must follow the leadership of the CCP and its “leadership core,” meaning Xi himself. Sinicization became policy when Xi cited it in his “Political Report to the 19th Party Congress” last October, wherein he noted that the party must “fully implement the basic goals of the party’s religious work, uphold the Sinicization of religion, and enthusiastically provide guidance to religion so that it can be compatible with the socialist society” (Gov.cn, October 27, 2017). Xi first mooted Sinicization in a United Front Work meeting in 2015, when he laid down his “four must-dos” policy: “We must uphold the direction of Sinicization; we must uphold the legal level of religious work; we must dialectically view the social function of religion; we must put emphasis on developing the [political] functions of members of religious circles” (Zhejiang Daily, July 6, 2015; Xinhua, May 20, 2015).

With Sinicization, Xi has departed sharply from the relatively tolerant religious policies of his two predecessors, former CCP general secretaries Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao. “The principle under which we handle relations with our religious friends is unity and cooperation in politics and mutual respect in the areas of thoughts and beliefs,” Jiang said in 1991. He added that the party and religious groups “respect each other in terms of ideas and beliefs. And this will never change” (People’s Daily, January 13, 1991). The former party chief also warned against using “leftist”—meaning ultra-conservative—tactics against religions. “We should not use a ‘leftist’ attitude toward religious beliefs just because Communists are atheists,” he said in 1990. “We cannot indiscriminately interfere with the beliefs of non-party members” [3].

Hu Jintao, who ruled from 2002 to 2012, was notoriously harsh toward Tibetans during his term as party secretary of the Tibet Autonomous Region from 1988 to 1992. After 2002, however, he repeatedly urged party cadres to “comprehensively and correctly implement the party’s policy regarding the freedom of religion, insist upon unity and cooperation in political [issues] and mutual respect in terms of beliefs” (China.com.cn, December 30, 2015). Overall, Hu maintained Jiang’s key religious dictum, including Christianity: “seeking unity and cooperation in politics, and [maintaining] mutual respect regarding beliefs” (CPPCC Net, February 26, 2014; Gov.cn, December 19, 2007).

“Scorched Earth” Policy towards Uighur Muslims

Xi’s measures toward Muslim Uighurs in Xinjiang, however, are more than simply a departure from his predecessors’ edicts; they have taken on the characteristics of a scorched-earth policy, one verging upon cultural and ethnic cleansing. In this, Xi’s goal appears to be less an attempt to render Islam compatible with socialist values, than brutal suppression of the religious practices and ethnocultural identity of Xinjiang’s estimated nine million Uighurs. Reports by Western news agencies and international human right watchdogs say that as many as 1 million Uighurs, mostly male, are locked up in institutions similar to WWII internment camps.

While the PRC government claims the camps are re-education facilities geared toward “curing” Uighurs of their separatist and terrorist proclivities, the reality is much more horrific. Inmates guilty of no specific crimes are separated from their families and subjected to bodily and mental torture. Only the small minority who convince their Chinese guards that they have forsworn Islam and embraced CCP teachings are released. “The human rights violations in Xinjiang today are of a scope and scale not seen in China since the 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution,” said Human Rights Watch in a report on Xinjiang. “The establishment and expansion of political education camps and other abusive practices suggest that Beijing’s commitment to transforming Xinjiang in its own image is long-term” (Human Rights Watch, September 9; Amnesty International, September 2018; BBC, August 30).

It is a tribute to China’s successful global soft-power projection that, while human rights NGOs have highlighted the deepening plight of Christians and Uighurs, few governments and parliamentary bodies have taken the Xi administration to task. Yet the enormity of the suffering and injustice in Xinjiang has finally been taken up by several Western governments. In late August, seventeen members of the US Congress wrote the State and Treasury departments, asking them to consider sanctioning Xinjiang Party Secretary Chen Quanguo and other cadres under the Global Magnitsky Act. The Magnitsky Act was originally designed to target Russian officials, but it has been expanded to allow sanctions for abuses anywhere in the world.

The Congressional letter said Uighurs were “subjected to arbitrary detention, torture, egregious restrictions on religious practice and culture, and a digitized surveillance system so pervasive that every aspect of daily life is monitored” (Reuters, August 30). In reaction to a UN report on the mass internment of Uighurs, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo on September 21 criticized Beijing for holding “hundreds of thousands and possibly millions of Uighurs… in so-called reeducation camps where they’re forced to endure severe political indoctrination and other awful abuses” (Hong Kong Free Press, September 25; Radio Free Europe, September 22). While it is not known whether—and when—Washington may announce sanctions against Chinese officials, the near-universal condemnation of Beijing’s draconian religious policy has made a big dent Xi’s claim that Beijing is forging a worldwide “community of common destiny.”

Dr. Willy Wo-Lap Lam is a Senior Fellow at The Jamestown Foundation. He is an Adjunct Professor at the Center for China Studies, the History Department and the Program of Master’s in Global Political Economy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is the author of five books on China, including “Chinese Politics in the Era of Xi Jinping (Routledge 2015).”

Notes

[1] As of 2010, there were 67 million Christians (58 million Protestants, nine million Catholics) in China, according to the Pew Research Center. Other independent estimates suggest Christians number between 100 and 130 million. Purdue University expert on Christianity Professor Fenggang Yang projects that if “modest” growth rates are sustained, China could have as many as 160 million Christians by 2025 and 247 million by 2032. See Eleanor Albert, “Christianity in China,” Council on Foreign Relations, March 9, 2018, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/christianity-china; Antonia Blumbert, “China On Track To Become World’s Largest Christian Country By 2025, Experts Say,” Huffington Post, April 22, 2014, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/04/22/china-largest-christian-country_n_5191910.html

[2] Author’s interview with a member of the Zion congregation, September 2018.

[3] See Jiang Zemin, “Maintain the stability and continuity of the party’s policy on religion,” in Selected Articles on Religious Work in the New Era, Beijing: Religion and Culture Press, 1995, p. 210. Also see “We must perform well in work toward religions,” in Selected Articles on United Front Work in the New Period (Sequel), Beijing: Central Party School Press, 1997, pp. 287-88.