The Death of Wilayat Sinai Spokesman Osama al-Masri and its Impact on the Insurgency in Sinai

The Death of Wilayat Sinai Spokesman Osama al-Masri and its Impact on the Insurgency in Sinai

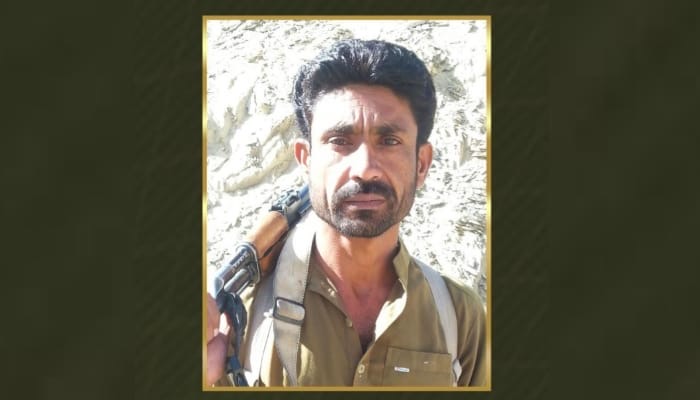

The Egyptian military dealt a serious blow to the Islamic State’s (IS) Egyptian province, Wilayat (province) Sinai, when an airstrike killed influential spokesman Muhammad Ahmad Ali al-Islawi, a.k.a Abu Osama al-Masri, last year. Al-Masri’s death was confirmed on November 5, 2018, when the North Sinai-based IS wilayat released a promotional video titled “The Path of Rationality From Darkness to Light,” mentioning his name followed by the expression, “May God accept him.” The statement confirmed news of al-Masri’s death a few months earlier (Mada Masr, November 17, 2018).

Reports indicated that al-Masri was between 37 and 40 years old when he died. He was not only an influential member and a spokesman of Wilayat Sinai; he was also responsible for the deadliest attack in Egypt’s modern history. In October 2015, he masterminded the downing of a Russian jet, which killed all its 224 passengers and crew shortly after its takeoff from Sharm el-Sheikh airport (al-Arabiya, November 8, 2015).

“We are the ones who downed it by the grace of Allah, and we are not compelled to announce the method that brought it down,” al-Masri said in a statement. The success of the attack, which came on the first anniversary of his allegiance to IS, was a “blessing of our gathering under a single banner and leader,” he said, referring to the group’s leader, Abu Bakr al-Bagdhadi (al-Youm al-Sabae, May, 18, 2015).

Al-Masri’s role in downing the Russian jet came to light even before his statement, when British intelligence confirmed through leaked phone calls among IS militants that he had planted an explosive charge in a luggage of a passenger jet with the assistance of a civil servant at Sharm el-Sheikh’s airport. As a result, Russian and British governments suspended their flights to Egypt. At that time, British officials expressed their readiness to dispatch a team of British Special Forces to Sinai to target al-Masri (Tahrir News, November 8, 2015).

After the military announced a large-scale “Comprehensive Military Operation,” which aimed to eliminate the country’s growing insurgency, it was likely that Egypt’s security apparatus heaved a sigh of relief when Wilayat Sinai confirmed al-Masri’s death from a military airstrike in June 2018. Indeed, al-Masri’s death has crippled the group’s terror activities, which had gained momentum after the Egyptian military, backed by popular protests, overthrew Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated president Muhammad Mursi in mid-2013 (Sada el-Balad, November 17, 2018).

Al-Masri was born into a reputable tribe and grew up in North Sinai Governorate. Other reports indicate that he was born in the Sharqia Governorate, located in the northern part of Egypt, and later moved with his family to Sinai.

Prior to the Egyptian uprising that led to the ouster of Mubarak in 2011, al-Masri had adopted an ultraconservative ideology of Islam as reflected in his extremist views, excommunicating and threatening the Egyptian state. Before joining Wilayat Sinai, he made a living as a Quran therapist, meaning he attempted to cure patients through the recitation of related verses from the Quran.

Other reports claim that al-Masri’s real name is Yossry Abdul Moneim Nofal, a former leader of the organization al-Najun Min al-Nar that appeared in the 1980s. The organization was similar in its tactics and ideology to the group Egyptian Islamic Jihad led by Ayman al-Zawahiri. Most members of al-Najun Min al-Nar were in their 20s. Nofal escaped from prison, along with most of the organization’s members who were in jail, benefiting from the security vacuum that accompanied the Egyptian uprising in 2011 (al-Jouf News, November 9, 2015).

In the aftermath of the uprising, al-Masri became the spokesman for Ansar Bait al-Maqdis (ABM), succeeding Abu Hamam, a.k.a Abu Doaa al-Ansry, who was killed in one of the military’s airstrikes against the group. Experts claim that al-Masri spent a year in Syria, where he received training in militant tactics, and was groomed to be one of IS’ leaders in Sinai. Al-Masri was the person who read the November 2014 rebranding statement, in which ABM announced allegiance to the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, becoming Wilayat Sinai (Mobtada, June 26, 2018).

Al-Masri appeared in several videos claiming Wilayat Sinai’s responsibility for large-scale attacks that killed dozens of military personnel, including an attack against military personnel in Sinai in October 2014, which left 33 soldiers dead. Wilayat Sinai showed a graphic propaganda video claiming responsibility and showing the execution of two simultaneous attacks (Masr al-Arabia, October 25, 2014).

According to some reports, al-Masri embraced extremist views and received militant training in Gaza and Syria. Some sources said he used to move back and forth from Egypt to Gaza, making use of underground tunnels on the borders between both countries (Al-Arabiya, November 8, 2015). Other reports indicated that he used to appear blindfolded ad was only recognizable in two videos he made, given he has vitiligo signs that mark his hands. (Tahrir News, November 8, 2015).

Al-Masri was IS’ main negotiator with the Bedouins of Sinai, given his negotiation skills and strong ties with tribes there. To that end, the leadership of the group assigned him to get closer to the tribes and tasked him to appeal and recruit young Bedouins, especially those who are frustrated with the military’s counterterrorism campaign (Aman, December 11, 2017).

In May 2015, al-Masri reportedly appeared in an audio statement posted on a prominent jihadist website, calling for attacks against Egyptian judges, after the group killed three judges in North Sinai, saying: “It is wrong for the tyrants to jail our brothers,” referring to judges. “Poison their food… surveil them at home and in the street… destroy their homes with explosives if you can” (al-Hurra, May 21, 2015).

The same year, al-Masri released a video showing the beheading of ten Bedouins, accusing them of being informants or spies for the Egyptian military. The video also showed IS executioners beheading four others for supposedly passing information to Israeli spies to assist in drone strikes (al-Arabiya February, 11 2015).

Maher Farghaly, an expert in militant organizations, said al-Masri is dubbed “The Mayor of IS” and released several threatening and provocative videos against the Egyptian military and police. One of his recordings called for Muslims to kill judges, which came shortly after IS killed three judges in Sinai in May 2015 at the peak of attacks against the Egyptian state (Mobtadaa, June 26, 2018).

As the military succeeded in targeting Wilayat Sinai’s high profile leaders, several lower-ranking members have become disaffected by IS’ failure to achieve any tangible progress in its war with the Egyptian state. Their complaints have led to their excommunication from the group. Jamaat Jund al-Islam, an al-Qaeda affiliate also known as Jama’ah Ansar al-Islam, released a video that included confessions from an IS dissident, who claimed that Wilayat Sinai was responsible for the al-Rawda mosque massacre that left 235 people dead during Friday prayers in 2017 (Al-Arabiya, November 12, 2017).

The dissident spoke on the growing hostility between al-Baghdadi’s organization and Hamas in Gaza, saying that one source of tension stems from the presence of several foreign fighters within IS. The dissident also pointed to Hamas’ accusation of IS members displaying moral debauchery.

The rising dissident in Wilayat Sinai was apparent when the group’s jurisprudence judge sentenced one of the group’s members to death, saying: “Today we will execute one of the apostates for smuggling weapons to Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades from Arish to Gaza Sector.” The Wilayat Sinai executioner was identified as the son of a prominent Hamas leader (Al-Masryoon, January 4, 2018).

Conclusion

Wilayat Sinai and other IS offshoots across the region are diminishing, disempowered, and undergoing a dismantling process, due to two factors.

The first factor is Egypt’s relentless and continued crackdown on militant strongholds and leading members, taking into consideration the potential emergence of mutated types of Islamist militants within the rugged and thinly populated northern Sinai. Still, targeting Wilayat Sinai’s influential leaders such as al-Masri has indeed broken the morale of the most powerful militant groups, whose regional structure is shaken up by the coordinated efforts of countries across the region. The military is increasing control over the country’s borders and drying up the financial and logistical resources that maintain the militants’ power.

Second, Wilayat Sinai’s strategy after the military’s wide-ranging counter–terror campaign is itself eroding the structure the group was built on. For instance, Wilayat Sinai has been engaged in clashes with tribes in Sinai as well as other militant groups. In addition, after targeting military checkpoints and vehicles frequently for almost two years, the group, as of 2015, has been targeting civilians such as Coptic Christians at their churches or monasteries, as well as Muslims during their prayers. This reflects the weakness and fragility of the group’s structure and leadership, given that such attacks are little more than an attempt to show that Wilayat Sinai still exists.

Last but not least, the rising dissent within the ranks of Wilayat Sinai has hollowed out the group from militant recruits. This has made it even easier for the military and police to target its influential members, who laid the foundation of militant activity and strategy, especially after the security vacuum that came in the aftermath of the Egyptian uprising in 2011.

For all the above-mentioned reasons, one can argue that al-Masri’s death has degraded Wilayat Sinai and made it voiceless, and thus badly affected its message and recruiting process.