Fractured Moldova’s Presidential Election Decided by European Diaspora Vote

Fractured Moldova’s Presidential Election Decided by European Diaspora Vote

Moldova’s two-round presidential election, on November 1 and November 15, was—above everything else—a clash of cultures. It pitted the incumbent Socialist, Russia-oriented President Igor Dodon, with his core electorate of aging and rural voters, against the Harvard-educated technocrat Maia Sandu, the candidate of educated urban voters, the young and the Moldovan diaspora in Europe. With Moldova itself evenly divided between two cultural matrixes, its diaspora voters in Europe tipped the balance.

Sandu won the November 15 runoff by an unexpectedly heavy margin, 58 percent against Dodon’s 42 percent. Two weeks earlier, she had outvoted Dodon in the first round narrowly, by 36 percent to 33 percent. Most forecasts had projected Sandu trailing Dodon in the first round and standing an even chance with him in the runoff. The turnout was 52 percent overall; and within that, it was higher in the European diaspora than in Moldova itself (Unimedia, November 1, 2, 16, 17).

The same candidates had competed in the 2016 presidential election runoff. Sandu, a novice politician at that time, lost with 48 percent to Dodon’s 52 percent. Sandu’s main target in that campaign was the country’s de facto ruler, oligarch Vladimir Plahotniuc, who controlled Dodon at that time. Plahotniuc’s support for Dodon more than offset Sandu’s diaspora support and made Dodon president.

The election just held was not a contest of programs or ideologies—e.g., left versus right, as Moldovan analysts traditionally stereotype it. Nor did it at any point become a geopolitical contest between Russia and the West, as international media often characterize it. This election was, however, a landmark in terms of Moldova’s strategic orientation defined as civilizational choice. This does imply keeping Russia out and bringing the West in Moldova (see EDM, October 19, 28).

The just-concluded election’s numerical data illustrates Moldova’s internal fractures, political deadlock, and the diaspora’s new and growing role as arbiter of Moldova’s elections (an offshore balancer sui generis) (Unimedia, November 16, 17).

Within Moldova itself, Sandu prevailed over Dodon by a razor-thin margin of 27,000 votes. But she garnered 244,000 votes in the diaspora, which lifted her far above the incumbent. The diaspora’s total vote went 93 percent for Sandu and only 7 percent for Dodon. It is a safe assumption that Dodon’s 7 percent share came mostly from Moldovans in Russia (these had favored another Russocentric candidate, Renato Usatii, in the first round).

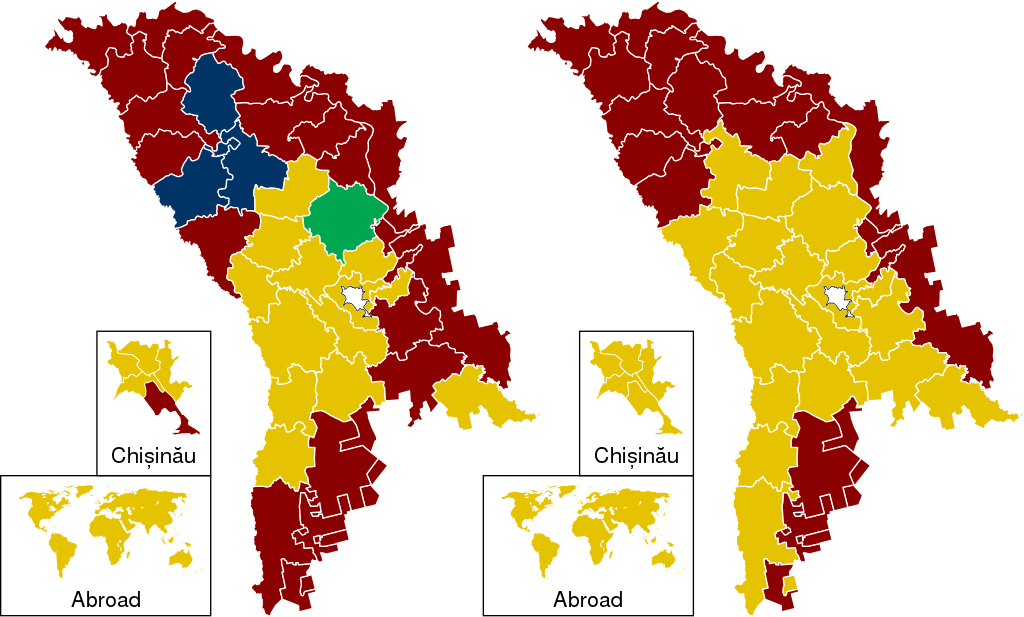

Moldova’s electoral map in this presidential election—just like the 2016 presidential election and 2019 parliamentary elections—displays a stark breakdown between compact “Yellow” and compact “Red” zones. Yellow stands for Maia Sandu’s party and, by extension, her allies in the pro-Western ACUM (“NOW”) bloc. The Red zones are fiefdoms of the Socialist Party and other Russophile forces (see below). This pattern has been in evidence in Moldova from the early 1990s onward (the blue color was used most of the time for contrast to red). And it has grown more entrenched with time. Russophile sentiment and corresponding voter constituencies predominate in Moldova‘s north and south (and in Transnistria, which plays a limited role in Moldova’s elections). Whereas pro-Europe (and, within this, pro-Romanian) sentiment and voters are predominant in Moldova’s central districts.

This presidential election has consecrated the new, Western dimension to Moldova’s electoral geography. But it has closely adhered to the accustomed electoral geography in the home country. Maia Sandu carried all of the central districts in the countryside by large margins. Additionally (and unprecedentedly) she carried all of Chisinau’s five inner-city boroughs, meaning that she received a substantial share of the “Russian-speaking” vote there. For his part, Dodon carried all of the nine districts in the north, the northern city of Balti (second-largest after Chisinau), the Gagauz-inhabited region (three southern districts) by 95 percent, the Bulgarian-inhabited Taraclia district (also in the south) by 93 percent, as well as the Transnistria vote by 86 percent.

Only 31,000 Transnistrian voters crossed the Nistru River to cast ballots in this election, out of the estimated 250,000 Transnistrians eligible to cast ballots in Moldova’s elections. This is a potential but never-yet used Kremlin resource against Chisinau (Ukrayinska Pravda, November 16). Sandu’s supporters had feared that a far larger number of Transnistria voters would be shipped to vote and lift Dodon to the top. But Moscow evidently decided not to help Dodon in this way (nor by mobilizing Moldovan guest workers in Russia, nor in any other way). And the unexpectedly large turnout of pro-Sandu voters in Europe matched or outweighed the estimated number of Transnistrians eligible to vote in Moldova (see above). This suggests that Russia would find it more difficult in the future to distort Moldovan elections by utilizing Transnistrian voters.

From a sociological perspective, the Moldovan village and the urban elderly supplied the bulk of Dodon’s supporters. The educated urban voters, urban youth and the diaspora in Europe (also mostly young) coalesced to form Sandu’s electorate.

Considering Moldova’s failed economy in the last ten years, it was the diaspora that kept the Moldovan boat afloat with their remittances. Now, for the first time, the diaspora is pulling the Moldovan boat slowly Westward with their votes.