Moscow in Urgent Search of New Space Partners

Moscow in Urgent Search of New Space Partners

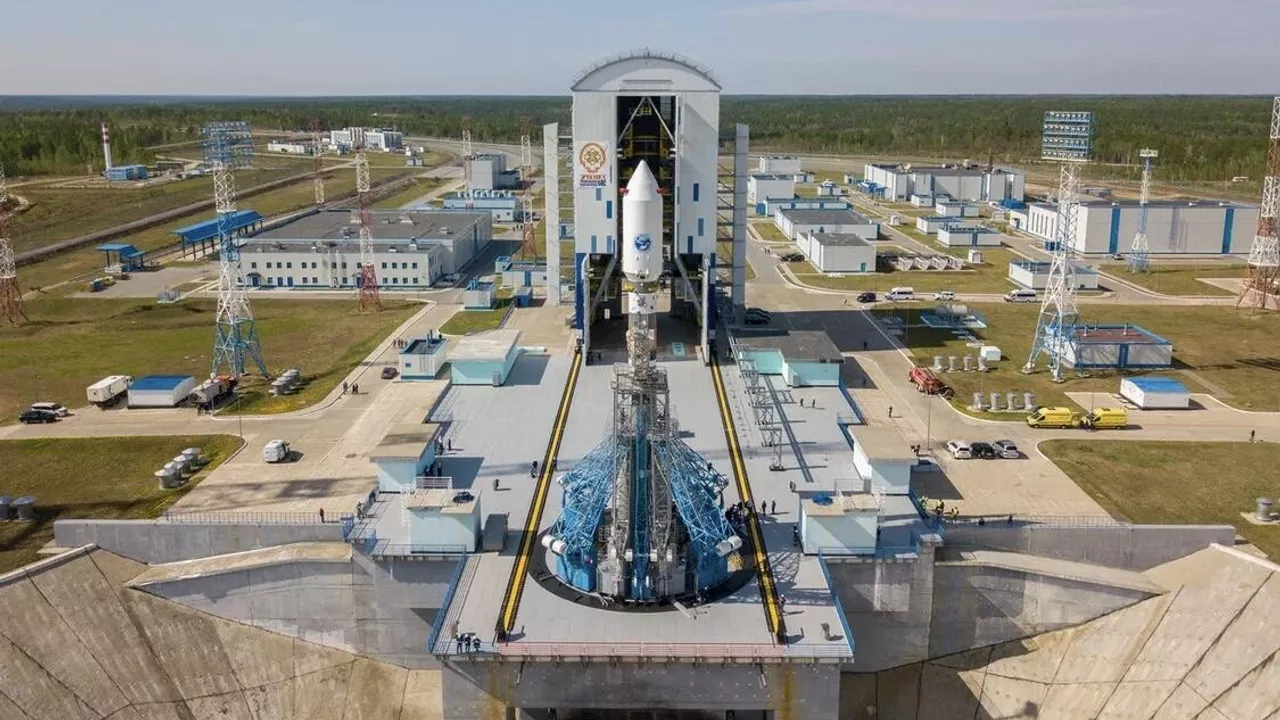

Russia is searching for new long-term partnerships in outer space instead of relying on cooperation with the United States, Europe, Canada and Japan. Recently, Yuri Borisov, head of state-owned Roscosmos, tried to develop space cooperation ties with Algeria and Egypt during his visits there and extended a public invitation to join Russia’s space program during the G20 meeting of the heads of national space agencies on July 6. Moscow hopes to advance cooperation with new partners on constructing and deploying satellites as well as planning and launching manned spaceflights, which includes the project on the new Russian Orbital Space Station planned to be operational sometime in the 2030s. In this, the Kremlin seeks to convince its new partners to agree to dock their respective national modules at the new space station (Kremlin.ru, June 30; Roscosmos.ru, July 6).

Two primary reasons underline this recent diplomatic activity. The first is Russia’s intention to maintain access to global markets for space-grade electronics and bypass sanctions. And the second is finding new financial resources for Roscosmos considering its net loss of $1.15 billion in 2021–2022.

Overall, the Russian space program is highly dependent on imported space-grade electronics. The only field that still avoids the embargo on these technologies is the production of small satellites for educational purposes, as they do not need space-grade electronics for their operation. Due to a short lifespan and relative technical simplicity, such satellites rely on commercial electronics and components produced in the US, Europe and other countries. The main manufacturers of these satellites are small private companies such as Sputnix (a subsidiary of AFK Sistema, which is under Western sanctions), Geoscan and others, as well as some major technical universities (Habr.com, October 25, 2022; RIA Novosti, June 27; Sputnix.ru; Spacepi.space, accessed July 6).

In a wider sense, Russia’s commercial, military and research satellites still rely on components imported from the US and Europe before 2022—and even before that, when severe sanctions were implemented under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act of 2017. For example, the Meteor-M No. 2-3 meteorological satellite that was launched into orbit on June 27 would have been impossible to complete without the import of critical Western components, likely sometime between 2014 and 2017 (Vniiem.ru, accessed July 6).

Moreover, Russian plans regarding the serial manufacture of small and medium satellites inevitably presume further dependence on Western electronics—whether it be completing Gazprom’s satellite assembly factory, which is behind schedule, or Roscomos’ plans for a factory that would have the capacity to manufacture 200–250 satellites annually. On the latter, however, the Russian space industry is not remotely close to being ready for such an undertaking, even according to official statements (Gazprom-spacesystems.ru, June 1; Sibisrskiy Sputnik, June 29).

Therefore, Russia may try to use deepened space cooperation with various Asian, African and Latin American countries as an offshore opportunity for its space industry to source space-grade electronics and components and thus avoid the Western embargo.

The future prospects of Russia’s manned space program are also unclear. Despite all the fanfare regarding the new Russian Orbital Space Station, the draft proposal for the station will not be completed until the end of 2023. Additionally, the only orbital module that has been produced in the past few years and that was originally planned as the last module of the Russian segment of the International Space Station needs a significant redesign (Roscosmos.ru, July 26, 2022; Interfax, December 26, 2022). In this way, attempts to engage countries like Egypt and Algeria on this project look similar to the attempts to engage India on projects for fifth-generation fighter jets and military transport aircraft during the 2000s and 2010s, which has had limited success. Briefly speaking, Russia faces severe deficits in human, financial and industrial resources to realize its own orbital space station alone.

Consequently, the idea of foreign modules onboard the future Russian orbital station means Moscow intends to use the new partnerships it is cultivating to gain offshore access to Western space-grade technology and industrial equipment. However, these efforts may bring about inconsistent results at best. It is hard to imagine that Egypt or Algeria possess the capabilities to produce their own orbital modules compatible with the Russian space station and spacecraft any time soon. Even so, the successful construction of joint manufacturing facilities in these countries, where the Russian-made modules could be completed with the sanctioned European- and American-made parts and then deployed into orbit as foreign modules, provides a possible option for Moscow in an effort to save its manned spaceflights and circumvent Western sanctions.

As a result, Roscosmos is increasing its foreign activity, as Russia’s storage of advanced electronics and components imported before 2022 is set to run out in the next two to three years. Finding and maintaining permanent access to advanced industrial equipment and the necessary financial resources to support Roscosmos’ work are also essential matters that still need to be resolved for Russia’s space program. In the 1990s, the United States saved the Russian space industry through contracts and direct investments. Now, the Kremlin hopes that Egypt, Algeria and other ambitious developing countries can save Russia’s space industry once again.