Rigging the Game: PRC Oil Structures Encroach on Taiwan’s Pratas Island

Executive Summary:

- Beijing’s relentless pressure on Taiwan now includes oil rigs: twelve permanent or semi-permanent structures and dozens of associated ships. The structures, which are owned by state-owned firm CNOOC, include seven rig structures, three floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) vessels, and two semi-submersible oil platforms. All are located within Taiwan’s claimed exclusive economic zone (EEZ) near Pratas/Dongsha Island.

- Intruding rigs that exploit natural resources without permission typify maritime gray zone operations conducted by the People’s Republic of China (PRC). They are designed to advance territorial claims, establish creeping jurisdictional presence in contested spaces, and shape the operational environment in Beijing’s favor without open conflict—often under the guise of commercial activity.

- CNOOC’s structures could facilitate a full range of coercion, blockade, bombardment, and/or invasion scenarios against Pratas or Taiwan more generally, particularly by enhancing end-to-end “kill chain” (C5ISRT) capabilities if outfitted with sensors.

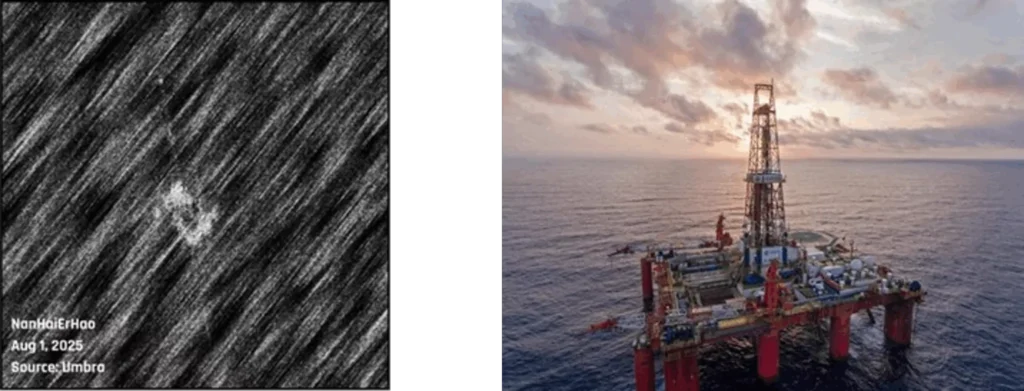

- Starting in July, CNOOC maneuvered the semi-submersible rig NanHaiErHao deep into Taiwan’s claimed EEZ. It is now only around 30 miles from Pratas’s restricted waters, although CNOOC rigs previously have come as close as 770 yards.

- By operating rigs in a neighbor’s claimed EEZ, Beijing already has succeeded with Taiwan where it failed repeatedly with Vietnam. Persistent Vietnamese protest made the difference on those previous occasions. Failure to protest today risks normalizing sovereignty shaving and encourages further encroachment.

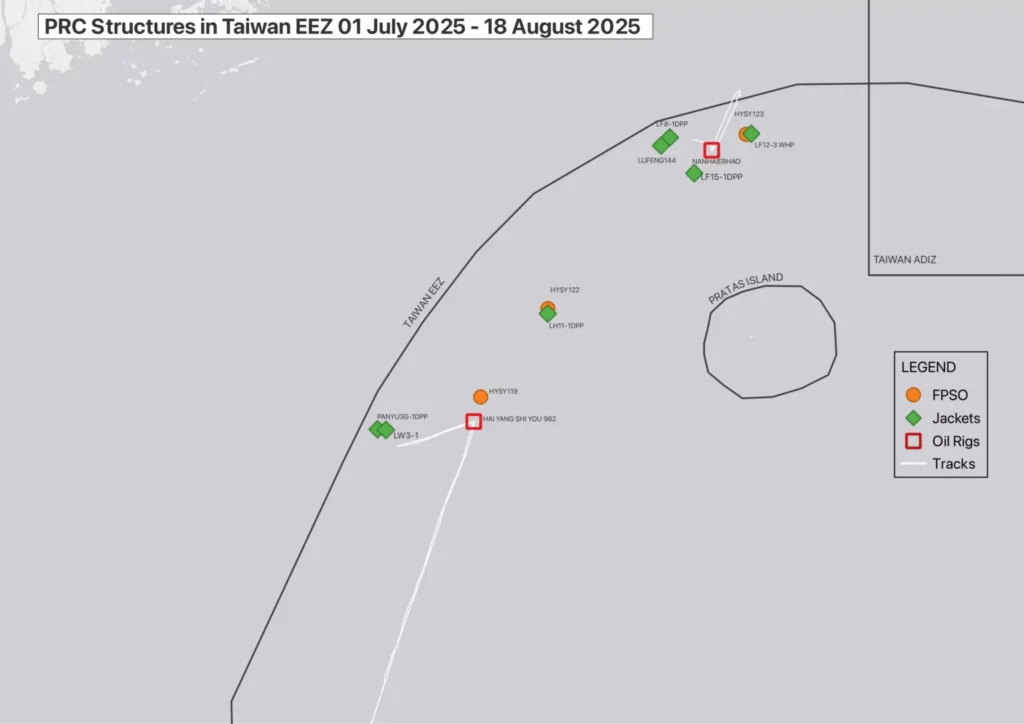

Oil rigs now constitute part of Beijing’s multidimensional campaign to undermine Taiwan’s sovereignty, which also includes cognitive, legal, and economic warfare. Taipei requires explicit permission to undertake “construction, use, modification, or dismantlement of artificial islands, installations, or structures” in its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) or on its continental shelf (U.S. State Department, November 15, 2005). By proceeding without permission, Beijing is rejecting Taiwan’s jurisdiction. This newest line of effort involves 12 permanent or semi-permanent structures, as well as dozens of associated support ships. All were operating within Taiwan’s EEZ near Pratas Island (a.k.a. Dongsha Islands; 東沙群島) between July 1 and August 18. Table 1 at the end of this article details these structures.

The 12 structures have been present since at least May 2020. They include—at a minimum—seven “jackets” (steel space-frame substructures of fixed offshore platforms that that support the weight of an oil drilling rig), three floating production storage and offloading (FPSOs—converted oil tankers with an oil refinery built on top), and five semi-submersible oil rigs (ScienceDirect, accessed August 18). [1] These are typically from Daya Bay Port east of Hong Kong in Guangdong Province. See the Appendix at the end of this article for an explanation of the fusion of remote sensing and AIS (automatic identification system) data used for the research underpinning these findings.

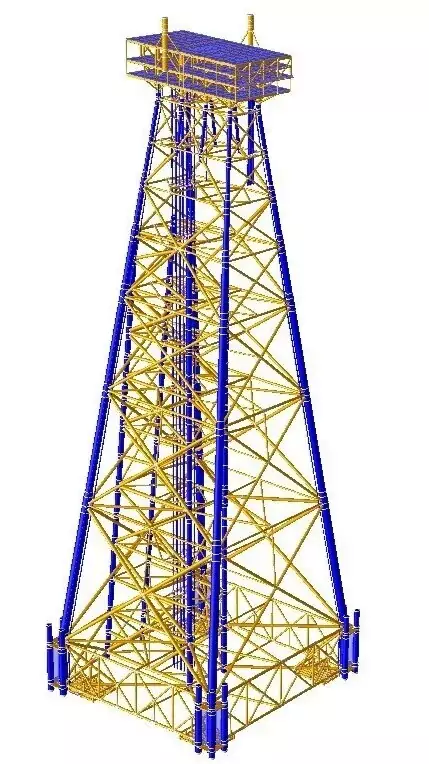

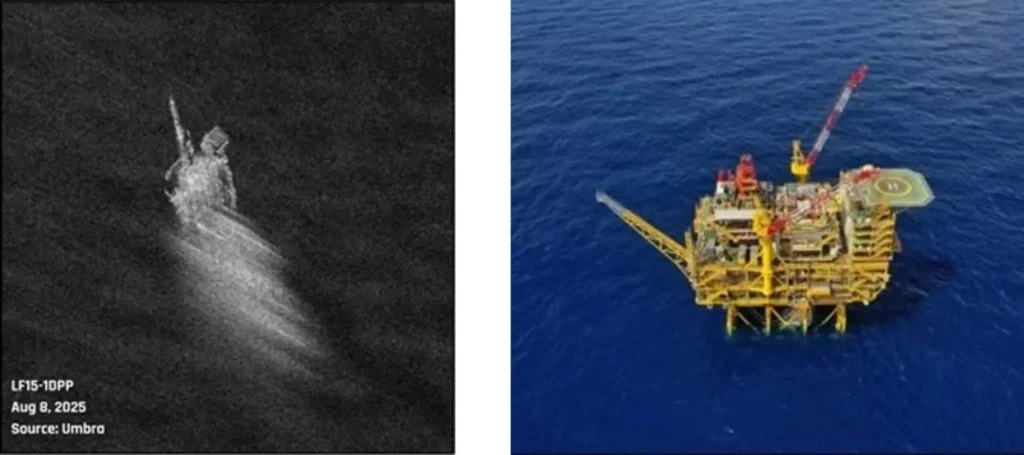

All the structures are owned and operated by China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC; 中国海洋石油总公司), a state-owned enterprise, and include some trailblazers. One fixed-jacket platform, CNOOC’s innovative LF15-1DPP (Deepwater Production Platform; 海基一号/Haiji-1), is the first 330-yard deepwater jacket in Asia (Xinhua, October 3, 2022; CNOOC, November 4, 2024). Non-jacketed rigs include storied veteran NanHaiErHao (南海二号/Nanhai-2), the PRC’s first semi-submersible drilling rig (China Daily; Sohu, May 28, 2019). Having first entered Taiwan’s claimed EEZ on June 23, 2021, it has been operating in and out ever since. [2] NanHaiLiuHao (南海六号/Nanhai-6), another CNOOC rig, has been operating in and out of Taiwan’s claimed EEZ since at least May 2020. On July 15, 2024, it came within 770 yards of Pratas’s restricted waters. In addition, among the three FPSOs is the first cylindrical FPSO to be designed and manufactured in the PRC (CGTN, August 18, 2023).

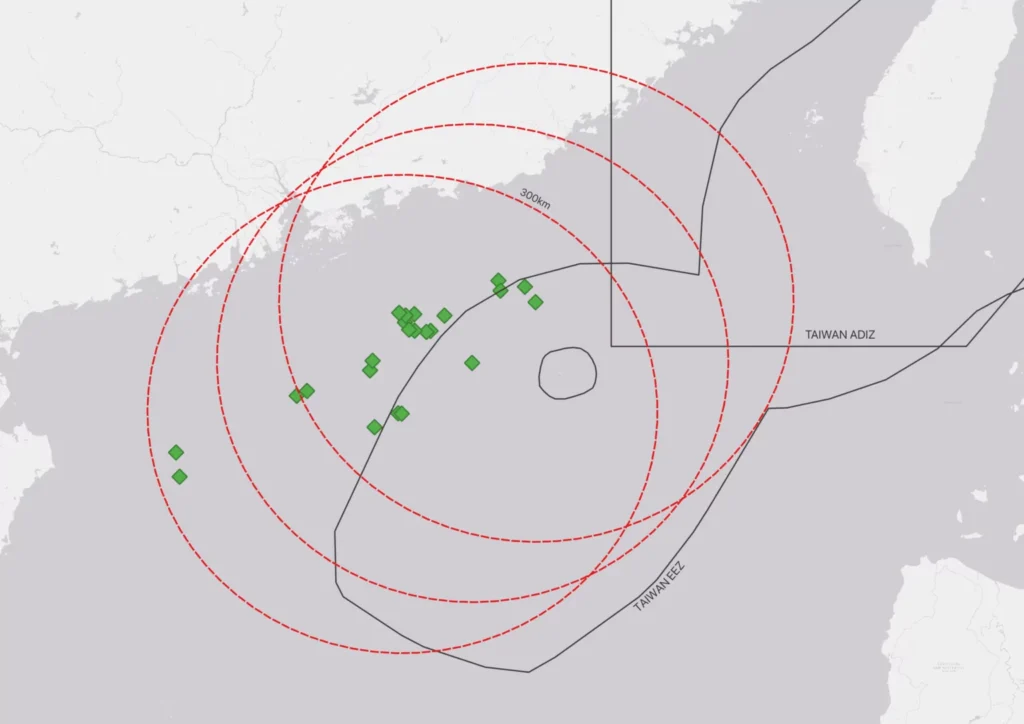

Figure 1: Location of Permanent Structures in Taiwan’s Claimed EEZ

(Source: ingeniSPACE, Starboard Maritime Intelligence)

State-Owned Structures Have Dual-Use Potential

CNOOC is a national asset tasked with far more than commercial considerations (Murphy, 2013). [4] In 2012, then-CNOOC Chairman Wang Yilin (王宜林) declared that “[l]arge-scale deep-water rigs are our mobile national territory and a strategic weapon” (Wall Street Journal, August 29, 2012; OffshoreTech LLC, accessed August 18).

CNOOC’s “jackets” are capable of hosting infrastructure to facilitate military operations against Pratas specifically, and Taiwan more generally. In fact, these latest structures may be more valuable for constraining Taiwan’s space than for their nominal commercial purpose of extracting oil. Their construction is an easily affordable effort for Beijing—significantly cheaper than South China Sea feature augmentation yet providing similar self-perceived benefits in terms of jurisdictional assertion and dual-use optionality. J. Michael Dahm has documented the formidable array of sensors, communications systems, and weapons that the PRC has deployed on Spratly outposts (Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, 2020). [5] Many of these could be applied to oil installations.

Figure 2: LF15-1 DPP Jacket Design

(Source: OffshoreTech LLC)

Given their size and support from seabed-grounded jackets, the rigs could easily accommodate surface-search navigation radars and electro-optical, SIGINT, and acoustic sensors for detection, as well as small-caliber guns. The PRC has experimented with various structures and systems as part of state-owned defense electronics developer China Electronics Technology Group Corporation’s (CETC; 中国电科) “Blue Ocean Information Network” (蓝海信息网络), integrating space, air, shore, sea, and submarine systems. These host, or serve as relays to, multifarious sensing platforms for X-band search radar, tropospheric scatter communication systems, and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) communications relays. Jacketed structures offer a fixed alternative for hosting CETC’s “Comprehensive Information Floating Platform” (综合信息浮台). One variant of its “Ocean E-Station” (海洋E站), the “Anchored Floating Platform Information System” (锚泊浮台信息系统), is particularly suited for mid-sea and fixed sea areas (as opposed to CETC’s island-based variant) (Exovera, February 7).

The structures’ helipads could support attack helicopters. Depending on their weight tolerance, they might support even larger kit, such as point-defense surface-to-air missiles and cruise-missile launchers. If developed as military facilities, lack of oil extraction equipment such as cranes and drill booms would leave more weight margin for armaments and fortification. In fact, if the jacket is modularized, the platform can easily be removed in its entirety and replaced with a dedicated militarized platform. Replacement is not a new concept. From 1967–88, Italy’s space program used three repurposed oil platforms off Kenya’s coast as a satellite launch-control-radar complex (Agenzia Spaziale Italiana, accessed August 18).

Figure 3: Movement of NanHaiErHao Oil Rig From July 17–24, 2025

(Source: ingeniSPACE, Starboard Maritime Intelligence)

Patterns of Suppression

Dual-use encroachment on Pratas affords gradual benefits without the onus of overt kinetic action. The Pentagon’s latest China Military Power Report argues that the PRC “could launch an invasion of small Taiwan-occupied islands” such as Pratas “with few overt military preparations beyond routine training.” It notes that this would entail much less risk than an invasion of larger, better-defended islands such as Matsu or Kinmen, even though such an operation is within the capabilities of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) (U.S. Department of Defense, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” December 2024). Worryingly, China Maritime Studies Institute affiliate Julia Famularo assesses similarly that the PRC “is gradually exercising the skills necessary to seize one of Taiwan’s outlying islands and potentially seek to force Taiwan leaders to the negotiating table” (Famularo, July 2025). [6]

Beijing’s operations impinging on Pratas are the latest in a pattern of similar activities in other contested regional waters. In each of the three near seas, the PRC has employed rigs and other infrastructure to assert sovereignty claims, while allowing for additional capabilities. Since 2018, Beijing has emplaced at least 13 lighthouse-shaped, solar-powered buoys in the Yellow Sea, each up to 43 feet high and 33 feet wide (KBS World, June 3; CSIS Beyond Parallel, June 23). In the Yellow Sea Provisional Measures Zone—where Seoul and Beijing’s EEZ claims overlap and where only fishing and navigation-related activities are permitted, per a 2000 agreement—the PRC has deployed a former oil rig managing two enormous aquaculture cages (Sealight, April 17; UN Food and Agriculture Organization, accessed August 18). It has blocked South Korean vessels from approaching the structures and declared temporary exclusion zones nearby, including in Seoul’s claimed EEZ. Former deputy registrar of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, Kim Doo-young, posits that the PRC could effectively deny over 4.6 square miles by installing 12 structures in a four-by-three grid (each 230 feet in diameter, spaced 0.6 miles apart). This would make it virtually impossible for Korean fishing or research vessels to enter the area. These structures have direct military implications, too. They parallel Pyeongtaek on the Korean peninsula, which could be targeted to attempt to impede U.S. forces based in Korea during a Taiwan contingency (Korea JoongAng Daily, March 25).

The PRC’s most extensive deployments are in the East China Sea, where it has 20 fixed rigs in the disputed Shirakaba/Chunxiao gas fields, with two recently added and at least three mobile drilling rigs active and sometimes connecting (CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative [AMTI], August 1). On June 24, Japan’s foreign ministry protested that “China has been taking steps to install a new structure” there (MOFA Japan, June 24; Japan Times, June 25). Tokyo consistently opposes the rigs, charging that they could support radars and military aviation (AMTI, August 5, 2015). In 2016, Japan’s defense ministry confirmed the installment of “an anti-surface vessel radar and a surveillance camera” on one of the platforms and reported its continued presence through 2023 (Japan Ministry of Defense, “Defense of Japan,” 2019, 2023). [7] In July 2023, according to its 2025 defense white paper, the ministry confirmed the existence of a buoy believed to have been installed by the PRC within Japan’s EEZ. Japan lodged a protest with the PRC and strongly demanded its immediate removal. As of February 2025, the buoy was no longer present. A second buoy, discovered in December 2024 within Japan’s EEZ, was also gone as of May 2025 (Japan Ministry of Defense, “Defense of Japan,” 2025; Research Institute for Peace and Security, May 30). For Tokyo, persistent objection seems to have made things better than they otherwise would be.

In the South China Sea, the PRC has deployed infrastructure assertively, to the point of generating crises with Vietnam. Hanoi has long been wise to Beijing’s game. In 1997 and 2004, Sinopec—a PRC “big three” national oil company together with CNOOC and PetroChina—deployed semi-submersible drilling rig Kantan-3 in Vietnam’s claimed EEZ. On both occasions, it withdrew the rig after Vietnamese protests (The Strategist, May 15, 2014). In 2014, the PRC staged an elaborate effort to protect another semi-submersible oil rig stationed within Vietnam’s claimed EEZ; this time, the rig was owned by CNOOC. The operation could serve as a model for a future defense of similar structures in Taiwan’s claimed EEZ (China Brief, June 19, 2014). Beijing’s actions operationalized and refined a layered multi-sea-force “cabbage strategy,” whereby Maritime Militia envelop a contested feature or structure, China Coast Guard vessels “protect” them, and PLA Navy warships maintain overwatch, ready to intervene. The PRC maintained a successful sea barrier against Vietnamese pressure for the removal of the rig (the HYSY-981) from disputed waters from May 2–July 15, 2014, keeping 110–15 vessels around the rig in a layered cordon extending out to 12 nautical miles (14 miles) and beyond (Vietnamese Embassy to Germany, June 5, 2014; CIMSEC, May 17, 2016; AMTI, July 12, 2017). It deployed roughly twice the maritime presence of Vietnam, leaving the latter no way to penetrate the defensive rings enveloping the rig (without the use of deadly force, at least). Four PLA Navy warships participated, as did 35–40 coast guard, 40 militia, and roughly 30 oil company and other commercial vessels (Andrew S. Erickson, February 7, 2017; CIMSEC, January 23, 2019). The critical stakes for Hanoi’s interests, coupled with Vietnam’s inability to match the PRC at sea despite its every incentive to do so and closer proximity to ports and supply lines, demonstrated the PRC’s qualitative and quantitative superiority over Vietnam’s sea forces. HYSY-981 was nevertheless relocated ahead of schedule, apparently in response to Hanoi’s sustained maritime resistance, Vietnamese public unrest, and government protest. Both aspects should resonate in Taipei, with the PRC now achieving against Taiwan what it was unable to achieve against Vietnam.

Figure 4: LF15-1DPP Fixed Deepwater Jacket Platform Oil Rig Captured With SAR (Left) and Optical (Right)

(Source: Umbra [L]; Dute News [R])

Figure 5: NanHaiErHao Semi-Submersible Oil Rig Captured With SAR (Left) and Optical (Right)

(Source: Umbra [L]; KK News [R])

Potent Precedents, Potential, and Pushback

Historical examples of installing sensors and weapons on rig-type structures and using them to support military operations underscore possibilities for both perceived utility and costly escalation. During 1942–43, Britain deployed Maunsell sea forts. Navy variants, which helped destroy a German E-Boat in World War II, were designed to deter, detect, and deny German air raids in the Thames estuary. They had twin reinforced concrete legs with steel decks mounting two 3.7-inch anti-aircraft guns, two Bofors anti-aircraft guns, and radar/operations spaces. Army variants for air defense, which were also present in the Thames Estuary as well as Liverpool Bay, comprised clusters of seven interlinked steel towers—four with 3.7-inch anti-aircraft guns, one with Bofors 40mm guns, one searchlight tower, and a central control/accommodation tower. A current example of the military relevance rig-type structures offer is the U.S. SBX-1 missile-defense ship, based on a semi-submersible oil platform and dominated by an enormous active electronic scanned array (AESA) radar (U.S. Navy, accessed August 18).

The 1981–88 Tanker War offers the most significant modern example of marine structures in kinetic warfare. Iran repurposed offshore oil/gas platforms as forward bases with radars, radios, and guns monitoring tanker routes and cueing Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy (IRGCN) attacks from speedboats, minelayers, and helicopters staged there (David Crist, “Gulf of Conflict: A History of U.S.-Iranian Confrontation at Sea,” July 1, 2009). More than one third of all Iranian attacks on shipping occurred within 50 nautical miles (58 miles) of three key platform clusters (Crist, The Twilight War: The Secret History of America’s Thirty-Year Conflict with Iran, 2010, p.210). Under the 1st Naval District command in Bandar Abbas, these observation-communications-attack posts astride key sea lanes had surface-search radar and radios/teletypes tracking merchant traffic and relaying targeting data. Operating undercover as National Iranian Oil Company employees, four Islamic Republic of Iran Navy (IRIN) observers manned each platform together with other personnel. Bandar Abbas relayed attack orders through the platforms’ radio network. IRGCN vessels surged from the nearest platform along a target ship’s anticipated course. Helicopters launched wire-guided anti-tank missiles.

Figure 6: Ranges for Hypothetical YJ-12 Anti-Ship Missile Batteries Stationed on Structures in Taiwan’s Claimed EEZ

(Source: ingeniSPACE)

On September 21, 1987, U.S. forces caught IRIN LST Iran Ajr mining Bahrain’s main channel. [8] The vessel had previously called on one of the platform clusters, although Tehran claimed it was routinely resupplying oil platforms (Naval History and Heritage Command, April 18, 1988). In response to subsequent Iranian attacks on U.S. vessels, [9] the U.S. Navy executed two calibrated strikes rendering most platforms inoperable. One, Operation Nimble Archer (October 19, 1987), targeted a cluster of three platforms. A frigate issued an evacuation warning, then three destroyers fired five-inch guns. One structure succumbed to gas flames. SEALs boarded the unshelled northern platform, collected accumulated and incoming telex messages, and set destruction charges (Crist, The Twilight War, 2010, p. 310–12). The other strike, Operation Praying Mantis (April 18, 1988), was the largest U.S. naval surface action since World War II. It targeted two of the most important IRGCN staging platforms. One suffered a similar fate as the platforms targeted the previous year, while at the other a stray shell struck a gas-separation tank, incinerating the Iranian gun crew and precluding boarding (Crist, “Gulf of Conflict, 2010, p.7–8; Crist, The Twilight War, 2010, p. 335–342). After a ceasefire, Iran demolished the platforms that the U.S. military had destroyed.

Monitoring Challenges

The persistent clouds over Pratas and its surroundings give the PRC convenient means to hide their movements and activities. Whether using exquisite or commercial means, electro-optical imaging as a monitoring option is of limited use. Furthermore, satellite constellation operators normally do not collect imagery beyond the coast. Even the European Space Agency’s Copernicus Program rarely covers so far out to sea. From an indications and warning perspective, the implication is that early-warning monitoring capabilities are limited to countries with all-weather imaging—such as SAR—and specialized human resources at their disposal (The Diplomat, August 16).

Conclusion

For now, CNOOC’s twelve permanent or semi-permanent structures near Pratas Island, which include seven rig structures, three FPSOs, and two semi-submersible oil platforms, are an additional component of a comprehensive toolkit supporting Beijing’s all-domain pressure campaign. This campaign seeks to expand control over the South China Sea via incremental extraterritorial gains, to strangulate and absorb Taiwan, and to surveil and probe potential adversaries who might intervene. Structures such as these, primarily composed of jackets, are easily modified. They can be temporary or permanent, commercial or military. Too long overlooked, they offer ambiguous optionality for peacetime-coercive or wartime benefits, aligning with Beijing’s preferred tactics. Monitoring these activities requires dedicated all-weather imaging resources to provide indications and warning.

CNOOC has imposed drilling rigs in Taiwan’s claimed EEZ in a way that it failed to do in Vietnam’s. Countering the PRC’s employment of dual-use infrastructure to undermine sovereignty is both possible and essential. As Tokyo and Hanoi’s experiences suggest, demonstrating cognizance of CNOOC’s structures and judiciously opposing them will not end all pernicious efforts; Beijing probes relentlessly. However, it could slow or halt PRC progress and pushiness short of a dangerous tipping point. Silence and inaction, by contrast, risk encouraging further advances. In a positive example of successful pushback, Taiwan’s Coast Guard routinely repels China Coast Guard vessels from Pratas restricted waters and expels or seizes intruding fishing boats (FocusTaiwan, June 22). Transparent monitoring of encroaching PRC oil structures and vessels is now urgently needed to ensure full maritime domain awareness and avoid further faits accomplis.

This article, derived completely from open sources, reflects solely the authors’ personal views. They thank numerous anonymous reviewers for valuable inputs.

Appendix: A Note on Methodology

The first comprehensive public findings on the PRC’s rig structures near Pratas were derived via open-source means by ingeniSPACE, a geospatial-intelligence company that helps users acquire, task, fuse, and analyze remote-sensing data across multiple satellite constellations. IngeniSPACE used AIS data for ships known to operate for CNOOC across Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan’s claimed EEZs. By examining sailing tracks and patterns-of-life for these support vessels, areas of interest were generated across the region where permanent structures and oil rigs were likely operating.

Specifically for the area around Taiwan-administered Pratas Island, analysts used pattern-of-life analysis to identify CNOOC jacket locations, active oil rigs, and oil and gas exploratory activities. Given the level of activity, it was ascertained that these oil rigs and associated vessels were manned and operational. IngeniSPACE then located public announcements concerning the rigs and support vessels and identified the companies involved. Houston-based OffshoreTech LLC apparently provided independent third-party verification of the jacket structural and load-bearing designs for a number of the fixed platforms within Taiwan’s claimed EEZ (OffshoreTech LLC, accessed August 18). This third-party verification uses in-place and pre-service analyses to verify that the jackets/structures have been installed securely (For instance, see OffshoreTech LLC, January 30, 2021). Separately, a profit-sharing announcement was found on CNOOC’s website referencing an arrangement between CNOOC (60.8 percent) and a South Korean company, SK earthon (39.2 percent), which also operates the LuFeng (LF) 12-3 Wellhead Platform (WHP) oil rig in the oil field known as LF 12-3 (MEE, September 2020; CNOOC, September 25, 2023).

Given persistent cloud cover at the area of interest, SAR was used to collect imagery instead of electro-optical means. Structures identified in SAR data were recognized as consistent with oil drilling platforms and FPSOs. IngeniSPACE’s findings are depicted visually throughout this article; further details are available upon request.

Table 1: PRC Structures in Taiwan’s Claimed EEZ Observed Between July 1 and August 18, 2025

| AIS Ship Name | MMSI | Type | Source |

| HYSY119 | 414030000 | FPSO | Baird Maritime |

| HYSY122 | 414937000 | FPSO | China Classification Society |

| HYSY123 | 414833000 | FPSO | People.cn |

| HAI YANG SHI YOU982 | 413491550 | Semisubmersible oil rig | HYSY982 Specifications |

| LF12-3 WHP | 413514170 | Jacket wellhead platform | LF12-3 Envt Assessment Report (pg. 15) |

| LF8-1DPP | 413535880 | Jacket drilling and production platform | LF Oil Fields Envt Assessment Report (pg. 26) |

| LF15-1DPP | 413336860 | Jacket drilling and production platform | LF Oil Fields Envt Assessment Report (pg. 23) |

| LUFENG144 | 413282540 | Jacket drilling and production platform | LF Oil Fields Envt Assessment Report (pg. 36) |

| LH11-1DPP | 413535880 | Jacket drilling and production platform | LH11-1 Envt Assessment Report (p. 15) |

| LW3-1 | 412476980 | Jacket central equipment platform | LW3-1 Envt Assessment Report (p. 1) |

| NANHAIERHAO | 412461260 | Semisubmersible oil rig | NanHaiErHao Specifications |

| PANYU30-1DPP | 413230000 | Jacket drilling and production platform | PY30-1 Envt Assessment Report (pg. 27) |

Notes

[1] Yong Bai and Wei-Liang Jin, Marine Structural Design. 2nd ed. (Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2016), 197–227.

[2] This oil rig appears on AIS (automatic identification system) as “NANHAIERHAO.” For readability, it is rendered “NanHaiErHao” throughout this article.

[3] The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) defines a flight information region as “an airspace of defined dimensions within which flight information service and alerting service are provided” (Skybrary, accessed August 18).

[4] Martin Murphy, “Deepwater Oil Rigs as Strategic Weapons,” Naval War College Review 66, no. 2 (Spring 2013), https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol66/iss2/9.

[5] J. Michael Dahm, South China Sea Military Capabilities Series: A Survey of Technologies and Capabilities on China’s Military Outposts in the South China Sea (Laurel, MD: Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, 2020), https://www.jhuapl.edu/work/publications/south-china-sea-military-capabilities-series.

[6] Julia Famularo, “Great Inspectations: PRC Maritime Law Enforcement Operations in the Taiwan Strait,” China Maritime Report No. 48 (Newport, RI: Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, July 16, 2025), https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports/48/.

[7] There is neither mention of the radar in the 2024 and 2025 editions nor information indicating its removal. The reason for the omission is unknown.

[8] LST stands for “landing ship, tank” and refers to ships that support amphibious operations by carrying tanks, vehicles, cargo, and landing troops directly onto a low-slope beach with no docks or piers.

[9] These attacks included the October 16, 1987 Silkworm strike on U.S.-flagged tanker Sea Isle City and April 14, 1988 mining of USS Samuel B. Roberts.