The Struggle to De-imperialize the Russian Psyche

The Struggle to De-imperialize the Russian Psyche

Executive Summary:

- Some Russian regional governors have established new headquarters to prevent separatism, nationalism, extremism, and mass riots.

- The creation of these headquarters raises doubts about the Kremlin’s confidence in public support for the war against Ukraine and Moscow’s imperial policies.

- Repression against Russian regionalists has increased since the start of the full-scale invasion, with many forced into exile but maintaining ties with compatriots in the country and advocating for more regional autonomy or full independence.

On December 29, 2023, several regional governors in Russia initiated the establishment of headquarters “to prevent separatism, nationalism, mass riots, and extremist crimes.” Those working at the headquarters include all senior regional officials and security officials from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Federal Security Service (FSB), and Russian National Guard (Rosgvardia). Thus far, the creation of four such headquarters has been confirmed in the Republic of Buryatia, Altai Krai, Voronezh Oblast, and Oryol Oblast (V-kurse-voronezh.ru, January 1; Burunen.ru, January 3; Newsorel.ru, January 7; Bankfax.ru, January 11). Each headquarters seem to have slight variations in their names, but all emphasize the fight against separatism in Russia. These moves were likely coordinated by the Kremlin on some level. The synchronized actions of regional authorities located far from one another indicates that the idea for these headquarters came from a central source. Similar headquarters have most likely been created in other regions, but information on these has not yet been published publicly or local officials are trying to keep them a secret. Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Moscow has gone to great lengths to tamp down separatist and regionalist sentiments, for fear that they could lead to the country’s ultimate rupture.

Victoria Maladayeva, an activist of the Free Buryatia movement abroad, believes that the new headquarters will mean a fresh wave of repressions against national movements in Russia’s regions. Under current Russian law, these movements are already heavily suppressed. Activists have been consistently targeted by the government, as “authorities throughout the country in the national republics have staged raids and imprisoned leaders of national opposition movements” (Doxa.team, January 5).

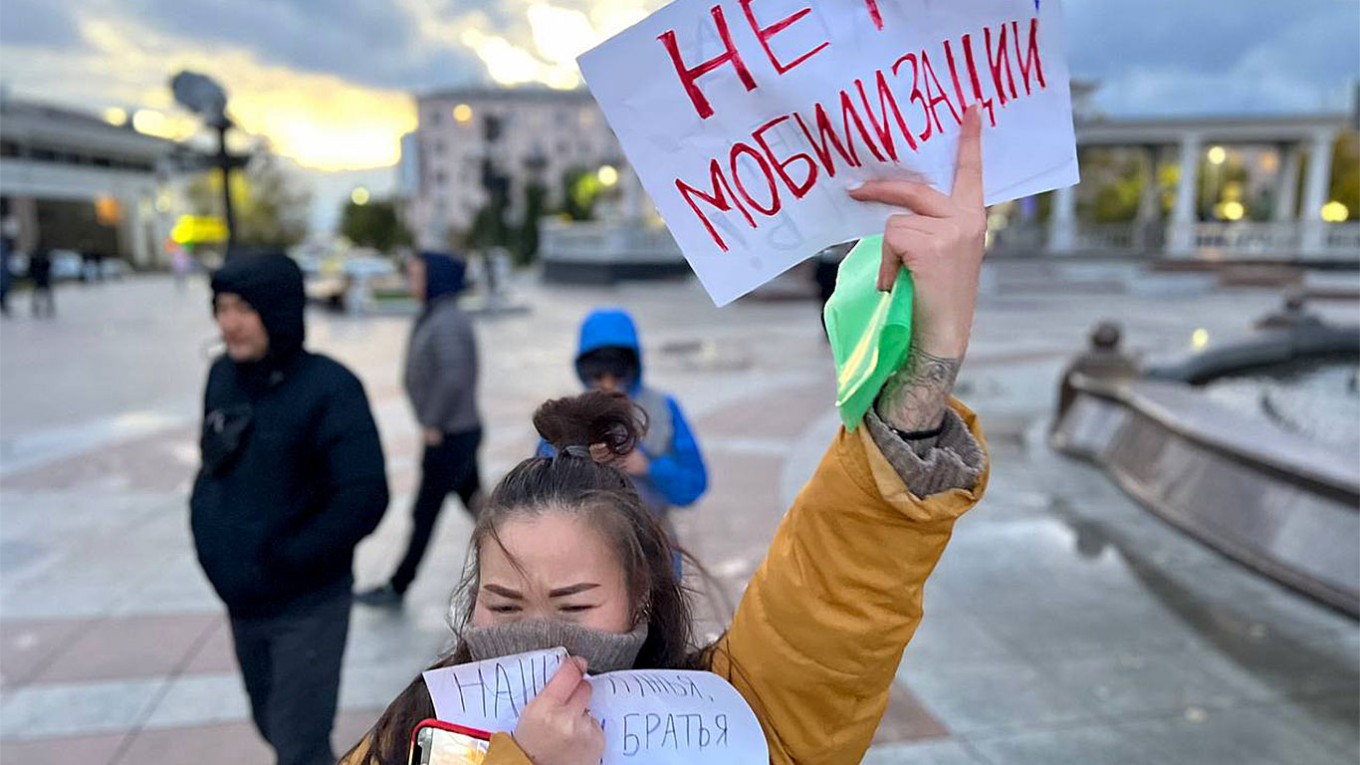

Moscow’s increased focus on combating regionalism comes at a time when many Russian citizens, especially non-ethnic Russians, are beginning to question Moscow’s justifications for the “special military operation” in Ukraine. For example, many ethnic Buryats question why they should die in Ukraine for the Kremlin’s imperial doctrine of the “Russian world” (Russkiy mir). Mobilization for the war was carried out en masse in Buryatia, with many of those recruited having already died on the frontlines. Protests have begun in various regions due to Russian military officials’ refusal to allow the mobilized to return home (Region.expert, December 6, 2023). The Kremlin will likely seek to discredit these activists by accusing them of “promoting separatism.” It is no coincidence that the new headquarters in Buryatia is called the “Headquarters for the Prevention of Separatism and Extremism.”

The headquarters to fight separatism and extremism are being established in predominantly ethnic Russian regions as well. Notably, headquarters have been created in the ethnically Russian Voronezh and Oryol oblasts and Altai krai, though no overt regionalist movements have been spotted in these regions. This raises the question of whether the Kremlin is actually afraid of “Russian separatism.” The emergence of movements for regional self-determination in ethnically Russian oblasts and krais is itself capable of blowing up the propagandist “unity” of Vladimir Putin’s empire. According to the 2020–21 census data, about 80 percent of the country’s total population live in ethnically Russian regions, while only about 20 percent live in national republics (Statdata.ru, accessed January 16).

The Kremlin often claims that all Russians support Putin’s policies. The creation of headquarters to combat separatism, however, demonstrates a lack of confidence on Moscow’s part. Various regionalist movements were active in the 1990s, from the Kaliningrad exclave to the Siberian Far East (Region.expert, November 19, 2020). In St. Petersburg, the “Free Ingria” movement was created, and mass demonstrations have taken place in Siberia in recent months (Gazeta.ru, May 1, 2016; see EDM, November 29, 2023). In 2020, at the famous protest in defense of the freely elected governor, Sergei Furgal, in Khabarovsk, anti-Moscow slogans became commonplace (Meduza, July 11, 2020).

In recent years, the Kremlin has sharply increased repressions against Russian regionalists. Many have been forced to emigrate as a result. While in exile abroad, these activists continue to advocate for greater autonomy or even the full independence of their regions. For example, the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum has gained more traction since the beginning of Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Representatives of various national and regional movements meet regularly as part of this organization to discuss the prospects for Russia’s de-imperialization (see EDM, August 10, 2022). In Russia, the forum has been declared an “undesirable organization,” and the authorities are threatening its participants with criminal cases (Svoboda, January 4). Although regionalists in exile have practically no influence on current Russian politics, they still maintain ties with their fellow citizens. Thus, the ideas of regional self-government have not completely disappeared. In the event of significant political upheavals in Russia, they may again gain mass popularity.

Many Russian regionalists in protesting the Kremlin’s imperial policies refuse to identify themselves as “Russians.” Vadim Sidorov, an ethnologist from Charles University in Prague, wrote last year about a deep crisis in the Russian psyche that began with the war in Ukraine (Region.expert, December 7, 2023). Sidorov postulates that Putin’s doctrine of the “Russian world” may be replaced by a new, more regional interpretation in the near future. The British and Spanish empires took some time to dissolve, and, while Russia is historically late, it will inevitably follow the same path. Today, English- and Spanish-speaking countries do not consider London or Madrid their capitals.

Moscow itself has its own regionalist project that involves the creation of a new federation within the boundaries of the current Central Federal District (Region.expert, January 9). Many citizens still in Russia are skeptical of this idea, as it seems to have been predominantly conceived by political exiles. Among Muscovites themselves, frustrations are growing that Moscow will turn into a giant imperial center, where problems with mass migration will only worsen and the city’s own historical culture will be erased. The Soviet Union partially collapsed due to the development of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, which appeared in the Soviet Union’s center and proclaimed its sovereignty in 1990. If a new “Muscovy” arises in the center of present-day Russia, history has every chance of repeating itself.

Western institutions and politicians often support the “all-Russian” opposition. Most of the opposition’s representatives, however, only want the replacement of the “bad” Kremlin tsar with a “good” one. This would likely result in the preservation of the same hyper-centralist state, perhaps slightly softened, which could lead to a repeat of Russian imperial cycles in the future. It would be much more far-sighted to support regionalist projects that today already advocate for the de-imperialization of Russia and mutual respect for national borders (T.me/freenationsrussia, October 5, 2023; Idelreal.org, December 14, 2023).