Xi Facing Opposition on Different Fronts in Run-Up to Key Party Plenum

Xi Facing Opposition on Different Fronts in Run-Up to Key Party Plenum

Introduction

A controversy is raging among the upper echelons of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) over General Secretary Xi Jinping’s advocacy of “common prosperity,” which has included forcing giant private enterprises to share their wealth with less privileged sectors (China Brief, August 26). At the same time, a thorough purge within the political-legal apparatus (政法系统, zhengfa xitong), which includes the police, secret police, the procuratorates and the courts, has turned up supposedly disloyal personnel who were—according to unofficial reports by NetEase (网易, wang yi), an online media platform that is run by the internet company of the same name—planning to take “illegal and improper” (不轨, bugui) actions against the top leadership (NetEase, September 14).

Xi’s retrogression to Maoism has sparked rare divergent views, as could be seen from how different sectors of the party reacted to a much-noted article by the ideologue blogger Li Guangman (李光满) entitled, “Each person can feel that a series of profound changes is happening” ([每个人都能感受到,一场深刻的变革正在进行!], Mei ge ren dou neng ganshou dao, yi chang shenke de biange zhengzai jinxing). First published on Li’s WeChat page on August 29, the piece was then simultaneously run by Xinhua, People’s Daily, the CCTV website, and various other prominent official media. Calling for a second Cultural Revolution, Li noted that recent instances of party authorities imposing discipline and fines on quasi-monopolistic private firms as well as social media bans on several “vulgar” and money-grabbing celebrities represented a prelude to “thorough transformations, which can also be called a series of profound revolutions.” He also asserted that deep-seated changes were happening in the economic, financial, cultural and political realms: “The theme of the revolution is changing a society centered on capital to a people-based one, as well as a return to the ‘original intentions’ (初心, chuxin) and quintessence (本质, benzhi)” of the CCP and Chinese socialism (Xinhua, August 29). Li claimed that strict measures against greedy capitalists and effeminate film stars were necessary to fend off “infiltration” from the United States (BBC Chinese Service, September 13; Radio Free Asia, September 3).

Public Dissent and Backpedaling

Li’s viewpoints seemed to echo statements made by Xi in recent months. At a meeting of the Central Finance and Economic Commission (CFEC) in August, Xi urged the rich to help the poor and pledged that the party would institute “a scientific public policy system that allows for fairer income distribution” (Xinhua, August 18). It is believed that only an article that has the backing of the party core (and likely Xi himself) can simultaneously be placed in all national-level papers. Only well-established liberal scholars such as the Peking University economics professor Zhang Weiying (张维迎) have openly criticized the concept of “common prosperity” espoused by Li and Xi (Freewechat.com, archived September 2). He asserted in a widely read article that “common prosperity” was not only against the basic laws of market economics, but that it might result in “common poverty” (Radio French International, September 4; Radio Free Asia, September 3). Apart from this public dissent, unarticulated opposition among senior cadres outside of Xi Jinping’s faction seems to be sufficiently strong to force an apparent backpedaling, with the “party core” quickly taking steps to convince the public that Deng Xiaoping’s reformist policies of economic liberalization and support for major market players will endure.

Take, for example, Beijing’s efforts to reassure private and foreign entrepreneurs that China’s four-decade-old reform and opening policy would not be diluted. In an early September commentary entitled “Insist on giving equal weight and strength to [the policies of] supervision and standardization and pushing ahead development,” ([坚持监管规范和促进发展两手并重、两手都要硬], Jianchi jianguan guifan he cujin fazhan liangshou bingzhong, liangshou dou yao ying) the CCP mouthpiece People’s Daily reassured readers that “China will unswervingly push forward the opening [policy] at a high level,” adding that there would be “a new framework of multi-faceted, multi-level, and comprehensive opening up [of the economy]” (People’s Daily, September 7). Around the same time, Vice Premier Liu He, a key advisor to Xi on economic issues, gave a speech at the opening ceremony of the China International Digital Economy Expo 2021 (中国国际数字经济博览会, Zhongguo guoji shuzi jingji bolanhui) stating that the government would “uphold the economic reform direction of the socialist market economy and insist upon implementing a high-quality [liberalization] policy.” Liu stressed that the “policy of supporting the development of the non-state sector will not change,” and added that “there is no change at the present moment, nor will there be changes in the future” (Xinhua, September 7).

Protests Raise Concerns About Social Stability

Various cities have been rocked by protests in the wake of the near bankruptcy of a number of high-profile real estate companies led by the Evergrande Group (恒大集团, Hengda Jituan). Evergrande, which also has substantial stakes in wealth creation products and electric vehicles, has run up debts of 1.9 trillion renminbi ($294.16 billion). Even as its management has denied speculation of bankruptcy, thousands of buyers of Evergrande properties and other products staged protests in Shenzhen, Zhengzhou and other cities over concerns that the group’s imminent default could affect private citizens’ housing investments. (VOAChinese, August 19; Radio Free Asia, September 15; BBC Chinese, September 14). Experts fear that a domino effect involving other heavily indebted “too big to fail” real estate developers might prompt more defaults and protests. Demonstrations have also been held by workers from newly shut down factories of foreign companies such as Samsung and Toshiba that reportedly closed due to global concerns about decoupling and manufacturing re-onshoring (163.com, September 12). Despite the state’s assertion in June that China has triumphed over absolute poverty, there is little evidence to date to show that Xi’s egalitarian policies have provided the middle and lower classes with enough material benefits to offset China’s rapidly widening wealth gap. Consumer confidence as represented by retail sales was up by just 2.5 percent in August, significantly lower than projections of around 7 percent (Finance.sina.com, September 16; Cn.wsj.com, September 16).

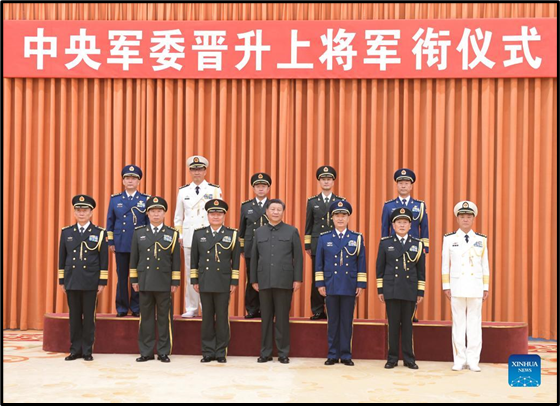

Concerns About the Loyalty of Security and Military Personnel

President Xi, who is also chairman of the CCP’s Central Military Commission, has relied on his solid grip on the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the political-legal apparatus to uphold social stability, as well as to shore up his preeminent position in the party ahead of the important Sixth Plenum Session of the 19th CCP Central Committee, which is due to be held in November (Chinanews.com, August 31). Yet Xi apparently harbors deep distrust of the police forces. In 2020 he launched the aforementioned purge of the political-legal system. The Central Political and Legal Commission (CPLC, 中央政法委员会, Zhongyang zheng fa weiyuanhui), which is China’s highest authority on police and judicial matters, is organizing several rectification exercises that are due to end next year. “Implementing the education and rectification of the national political-legal team is a major decision-making of the party center with comrade Xi Jinping as its core,” said Chen Yixin (陈一新), director of the General Office of the CPLC. He added that these purges would amount to “making deep cuts into the bones to take out the poison.” During the rectification drive from February to July this year, 178,431 personnel were subject to investigation and punishment. The campaign also encompassed 1,258 heads of departments including the Deputy Ministers of Public Security Meng Qingfeng (孟庆丰), Meng Hongwei (孟宏伟), and Sun Lijun (孙立军) (Liaoning Daily, September 17; SPP.gov.cn, August 30; Court.gov.cn, August 30).

Even more stunning is authorities’ disclosure in September that they had isolated a “conspiratorial clique” centered upon several senior police officers mostly from Jiangsu Province. This was exclusively reported by NetEase and picked up by the news portal Sohu.com. According to the unofficial media reports, the ring leader was Luo Wenjin (罗文进), head of the General Criminal Investigation Brigade of the Jiangsu Police Department. Luo’s co-conspirators included the former secretary of the Jiangsu provincial Political-Legal Committee and head of the Jiangsu provincial police department, Wang Like (王立科), and the executive vice president of the Jiangsu People’s Procuratorate Yan Ming (严明). They were aided by two more cadres from outside of Jiangsu Province: Deng Huilin (邓恢林), a former Chongqing deputy mayor and police chief who also once served as director of the CPLC General Office, and the late billionaire entrepreneur Lai Xiaomin (赖小民) the former chairman of the mammoth Huarong Asset Management Company who was sentenced to death on charges of bribery, embezzlement and bigamy in January. Also related to this clique was the Shanghai deputy mayor and municipal police head Gong Dao’an (龚道安). The NetEase article asserted that Luo and Deng regularly “made ungrounded criticisms of central policies and cast aspersions on central leaders.” It also disclosed that the group was “planning something illegal and improper” when party leaders were due to take part in commemorative activities related to World War II in Nanjing, capital of Jiangsu (NetEase, September 14). Their plotting was foiled by the Ministry of State Security (Radio Free Asia, September 16; Wenxuecity.com, September 16).

That Xi’s hold on China’s security forces including the PLA leadership is less than ironclad was recently demonstrated by the unexpected leadership changes of the pivotal Western Theatre Command (WTC)—China’s largest military region that covers the strategic border regions of Xinjiang and Tibet as well as overseeing military relations with India and Afghanistan—four times in less than a year. In December 2020, WTC commander General Zhao Zongqi (赵宗歧) stepped down upon reaching the retirement age of 65. He was replaced by the Deputy Commander of the Central Theatre Command (CTC) General Zhang Xudong (张旭东, born 1962), who is considered a protégé of Xi. General Zhang only served for six months. His replacement was the former commander of the Central Theater Command (CTC) Land Forces General Xu Qiling (徐起零, born 1962), who was only four months younger than Zhang. General Xu served in this post for all of two months. In September, it was announced that the former Xinjiang District Commander General Wang Haijiang (王海江, born 1964) had been promoted to lead the WTC. There had been speculation that both Generals Zhang and Xu suffered from health problems. China’s official media has not disclosed whether these former commanders have been given new jobs. More importantly, there is speculation that these extraordinary personnel changes may have involved issues of loyalty to the CMC chairman (Ming Pao [Hong Kong], September 8; New Beijing Post, September 7; SCMP, August 5; The Hindu, July 6).

Despite these repeated reshuffles, Xi still appears to harbor doubts about the loyalty of the military leadership. This was evident in a recent article in Seeking Truth (求是, Qiushi), the CCP’s leading theoretical journal. A piece written by the Army Political Work Institute of the Academy of Military Sciences, which was published on September 16, warned against ideological lapses such as “individualism, liberalism, centrifugalism… and cliquishness” among PLA officers. It also noted that the party leadership’s success in crushing Marshal Lin Biao’s coup d’etat attempt against Chairman Mao in 1971 was due to “the entire army resolutely heeding the party’s directives” (Qiushi, September 16).

Conclusion

Notwithstanding these contretemps, Xi has continued his policy of forcing multinational giants such as Alibaba and Tencent to stop their monopolistic practices and to sell some of their lucrative divisions to the state sector. Moreover, in a concerning echo of the strict norms imposed on society and culture during the Cultural Revolution, official censors and commissars have come up with new rules strictly regulating the entertainment and media sectors—as well as the salaries of big stars (Chinanews.org, September 17; HK01.com, September 17). However, it is also clear that Xi is facing substantial if as yet unspoken opposition in the run-up to the all-important Sixth Plenum in November as well as the 20th Party Congress next year.

Despite facing significant domestic and foreign challenges, Xi is focusing his energy on drafting a historical document examining the many achievements of the party over the past century, which will be unveiled at the Sixth Plenum. The document will heap eulogies on the successful rule of the CCP—in addition to likely emphasizing the larger-than-life contributions of Mao Zedong and his successor Xi Jinping. This will be the third seminal historical reassessment of the party since a similar document was drafted under Mao in 1945 and another one was orchestrated by Deng Xiaoping in 1981. The 1945 “Resolution on Certain Historical Questions” ([关于若干历史问题的决议], Guanyu ruogan lishi wenti de jueyi) justified Mao’s condemnation of early CCP leaders such as Zhang Guotao (张国涛) and Wang Ming (王明). The 1981 “Resolution on Certain Questions in Party History since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China” ([关于建国以来党的若干历史问题的决议], Guanyu jianguo yilai dang de ruogan lishi wenti de jueyi) condemned Mao’s “ultra-leftist” mistakes during the Cultural Revolution and gave the theoretical underpinning to Deng’s Reform and Opening Policy.

It is expected that the historical document to be released at this year’s Sixth Plenum will further bolster “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics in the New Era” (习近平新时代中国特色社会主义思想, Xi Jinping xin shidai Zhongguo tese shehui zhuyi sixiang) Yet whether Xi can effectively use the document to bolster his power depends on the outcome of on-going controversies among senior party cadres regarding his revival of Maoist concepts including “common prosperity.” Also important is whether Xi can purge the PLA and the political-legal apparatus of untrustworthy cadres who might challenge his supremacy.

Dr. Willy Wo-Lap Lam is a Senior Fellow at The Jamestown Foundation and a regular contributor to China Brief. He is an Adjunct Professor at the Center for China Studies, the History Department, and the Master’s Program in Global Political Economy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is the author of five books on China, including Chinese Politics in the Era of Xi Jinping (2015). His latest book, The Fight for China’s Future, was released by Routledge Publishing in July 2019.