Xi’s Op-Ed Diplomacy: Selling the “China Dream” Abroad

Publication: China Brief Volume: 14 Issue: 18

By:

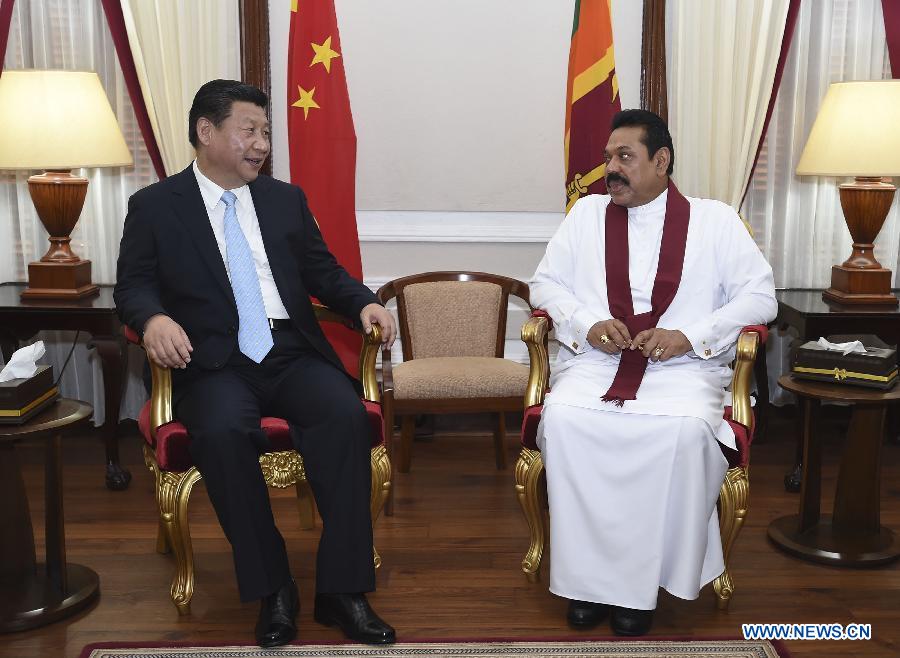

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s six-day trip to South Asia during September 14–19, on state visits to the Maldives, Sri Lanka and India, redoubled China’s efforts to increase its presence in the Indian Ocean while also trying to improve its relations with neighboring India. Xi signed major economic agreements in each country, including a $20 billion investment in Indian infrastructure and cooperation on a $1.3 billion port project with Sri Lanka. Xi’s tour also included public diplomacy with a personal touch—he published signed articles in the leading newspapers of each country. These articles prominently feature Xi’s concept of the “China Dream” as an alluring component of increased bilateral cooperation, serving his foreign policy goal of increasing Chinese soft power abroad while also burnishing his credentials as an inspirational leader at home.

Repurposing the Op-Ed

Xi appears to be the first Chinese president to regularly publish articles in major national newspapers on the first day of his foreign visit. Xi began publishing signed articles, shuming wenzhang, in foreign countries when he visited Europe this March, penning op-eds at each stop in Holland, France, Germany and Belgium (see also China Brief, April 9; Xinhua, April 2). Xi appears to have adopted the public outreach campaign from Premier Li Keqiang, who began this practice in Spain in 2011. [1] By the author’s count, Xi has published 10 articles abroad and Li has published 13. Of note, Xi did not publish any shuming wenzhang during his tour of South America this July, but did conduct a written group interview with a major newspaper from each country on his trip, which followed largely the same style (Xinhua, July 15). [2] By comparison, U.S. President Barack Obama similarly publishes op-eds when he travels on state visits abroad (White House, April 16, 2009).

Xi’s articles represent a break from tradition and reflect his more personal approach to diplomacy. Chen Mingming, vice president of the Translators Association of China and former ambassador to New Zealand, told Changjiang Daily that Xi’s decision to publish op-eds was “innovative,” since past Chinese presidents usually accepted interviews by local media while premiers wrote op-eds (Changjiang Daily, March 27). For example, then-President Hu Jintao and Xi, as vice president, both conducted written interviews with the Washington Post before their 2011 and 2012 visits to the United States, respectively (Washington Post, January 16, 2011; Washington Post, February 12, 2012). Tsinghua University professor Lu Shiwei explained that the op-eds, intentionally published in “authoritative local newspapers,” serve as an “excellent response” to “all types of analysis and speculation” by foreign media before the visit. Lu added that Chinese leaders usually review the op-ed personally after it is drafted, with expert input and edits to ensure acceptability in the host country (Changjiang Daily, March 27).

Your Dream Is Our Dream, We All Dream Together

Xi’s op-eds largely reflect his own ambitions for China, especially the “China Dream” and the economic reforms announced in November 2013 at the Third Plenum, and seek to relate these efforts to his host country (see also China Brief, November 22, 2013). In connecting the two countries, Xi invariably references their shared history, highlighting an era of Chinese prosperity. Xi noted Ming dynasty explorer Zheng He’s voyages in the Maldives, Mongolia’s role in the ancient Silk Road and Germany’s shared status with China of “[prominently embodying] the Eastern or Western civilizations” through their proud history of philosophers (Xinhua, March 28). This shared history is repurposed as the basis for the host country’s contemporary cooperation with China’s policy initiatives. The Maldives’ location in the Indian Ocean provides it a new role in China’s “21st Century Maritime Silk Road” and Mongolia’s boundary with China affords it inclusion in Beijing’s “Silk Road Economic Belt” (see “Xi and Putin in Ulaanbaatar: Mongolia’s Balancing Act,” in this issue).

The “China Dream” plays a prominent role in Xi’s efforts to encompass the host country’s ambitions within China’s own, especially for Asian countries. In Sri Lanka’s Daily News, Xi’s article was titled “Let Us Become Partners in Pursuit of Our Dreams,” and he told Sri Lankans that “The Mahinda Chintana, which represents Sri Lanka’s dream of national strength and prosperity, has much in common with the Chinese dream of realizing the great renewal of the Chinese nation” (Daily News [Colombo], September 16). In Seoul, Xi said that China and South Korea both need a “peaceful external environment” because China is pursuing the “China Dream” and South Korea is also creating “the Second Miracle on the Han River” (Xinhua, July 3). Xi also used the “China Dream” to bridge tensions with India, as he wrote that “our respective dreams of national renewal are very much aligned with each other. We need to connect our development strategies more closely and jointly pursue our common dream of national strength and prosperity” (The Hindu, September 17). This rhetoric echoes Xi’s May speech at the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA), where he said, “The Chinese people, in their pursuit of the Chinese dream of great national renewal, stand ready to support and help other peoples in Asia to realize their own great dreams” (see also China Brief, July 31; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, May 21). However, the “China Dream” apparently is not universal, as he mentioned it in every Asian country as well as France and Belgium, but not Holland or Germany. [3]

This emphasis on the “China Dream” abroad appears exclusively by Xi, as by the author’s account, none of Li Keqiang’s 13 signed articles have contained the phrase “China Dream” or “revitalization of the Chinese nation,” reinforcing Xi’s ownership of the concepts (see also China Brief, March 28, 2013; China Brief April 25, 2013). The “China Dream” also ties into Xi’s broader efforts in regional diplomacy, as he pointed out during the October 2013 periphery diplomacy conference that “good peripheral diplomacy […] is a requirement for the realization of the Chinese dream of national rejuvenation” (see also China Brief, November 2, 2013; People’s Daily Online, September 22).

Economic Cooperation Makes Dreams Come True

China’s economic reforms are also compared favorably to the local economy’s development path as a way to merge each country’s “dream.” In France’s Le Figaro, after explaining Beijing’s strategy for realizing the “China Dream” as “advancing the new type of industrialization, IT application, urbanization and agricultural modernization,” Xi said that “France, on its part, is stepping up its structural reform while working to ensure growth […] and fulfill the new French dream. Both China and France are reform-minded nations” (Xinhua, March 26). In Germany’s Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Xi linked the Third Plenum reforms with Germany’s “Industry 4.0” strategy and “energy transformation,” calling for “a new stage of ‘precision running-in’ and ‘seamless docking’ ” in Sino-German economic cooperation (Xinhua, March 28). Writing in India’s The Hindu, in English, and Dainik Jagran, in Hindi, Xi said that “the combination of the ‘world’s factory’ and the ‘world’s back office’ will produce the most competitive production base and the most attractive consumer market” (The Hindu, September 17).

In Mongolia, Xi explained the “China Dream” as achieving a moderately well-off society by 2020 and having a strong and prosperous modern socialist nation by 2049, evidently changing its definition from his earlier article in France to cater to his Mongolian audience. Xi wrote in four Mongolian newspapers that “the Mongolian people are also currently striving forward on their road of reform and development […] continuing to deepen the development of Sino-Mongolian relations and cooperation has come at the right time” (Xinhua, August 21). Explaining the link between economic cooperation and the “China Dream,” Qu Xing, president of the China Institute of International Studies, told Xinhua, “China is trying to achieve the Chinese dream. Mongolia is also at a crucial period of economic development, which indicates that there will be new contents in the economic and trade cooperation between the two countries” (Xinhua, August 19). This focus on similar reform paths as a binding part of Beijing’s relationships echoes Xi Jinping’s ongoing emphasis on “development as the key to peace” (see also China Brief, May 23).

The articles also highlight political solidarity between the two countries. Xi defended Sri Lanka from human rights criticisms by citing China’s long-standing principle of non-interference, as he wrote that China “resolutely opposes any move by any country to interfere in Sri Lanka’s internal affairs under any excuse” (Daily News, September 16). Citing France’s status as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, Xi said the two countries, “have the capability and wisdom to make good proposals and good initiatives to advance world multi-polarity and democracy in international relations” (Xinhua, March 26). Noting the world is “[moving] towards multipolarity,” Xi called on India to work with China to “make the international order more fair and reasonable, and improve the mechanism and rules of international governance, so as to make them better respond to the trend of the times and meet the common needs of the international community” (The Hindu, September 17). This was an obvious nod to their cooperation on the BRICS’ New Development Bank and increasing their influence in Western-dominated international institutions.

Xi’s op-eds appear targeted at foreign elites, despite the image of him engaging in grassroots diplomacy through a newspaper article. Xi’s efforts to extend the “China Dream” beyond its original domestic context, especially when combined with a heavy emphasis on bilateral economic cooperation, suggest a revamped soft power campaign linking foreign elites’ economic future with China’s national rejuvenation and development strategy. Both of the national dreams Xi referenced for Sri Lanka and South Korea, “Madhina Chintana”—President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s vision to revive his country’s economy after the end of the civil war—and the “Second Miracle on the Han River,” respectively, are signature policies of their leaders, enabling Xi to personally tie their government’s development strategies to his own.

Signaling Back Home

Beyond advocating his initiatives to China’s neighbors and friends, Xi’s op-eds also support his efforts to rebrand the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) at home. Xi’s articles have received regular billing on CCTV’s nightly news program and have gained traction in the state-run media. The Chinese media paid greater attention to Xi’s op-eds in South Asia than his earlier articles in Europe, with CCTV’s coverage nearly doubling in length on average. One headline asked “What Signal Did Xi Jinping’s Signed Article in the Sri Lankan Media Send?,” and other articles noted his use of Deng Xiaoping’s concept of the “Asian century” and Xi’s fondness for classical Chinese phrases, which are included in every article (People’s Daily Online, September 16; Beijing Times, September 18; People’s Daily Online, September 14). The Chinese media also reported extensively on the op-eds’ reception abroad, noting the leaders of Mongolia, Belgium and the Maldives read and supported the article, as well as the “high praise” Xi’s article received in South Korea (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, August 21; Xinhua, July 3). Xi’s efforts to extend the “China Dream” abroad are intended to demonstrate its global influence and reaffirm to the Chinese people that their quest for national rejuvenation resonates with other nations, especially in Asia. This, in turn, may restore some people’s faith that the Party can pursue equally successful economic reforms at home.

Notes

- Other senior Chinese leaders have written in foreign newspapers without visiting the host country, including Vice Premier Wang Yang’s July 2013 article on the U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue in the Wall Street Journal (Wall Street Journal, July 8, 2013).

- On his way to South America, Xi Jinping also made a technical stop in Greece, where he met with Greek President Karolos Papoulias over lunch. He did not publish an op-ed in Greece, likely because the visit was announced last minute and Li Keqiang had just visited and published an op-ed in June (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, June 18).

- Xi Jinping also did not mention the “China Dream” in his article during his visit to Tajikistan, where he attended the Shanghai Cooperation Organization meeting. This is likely because the focus of the visit was multilateral cooperation on security issues (Xinhua, September 10).