Terminal Authority: Assessing the CCP’s Emerging Crisis of Political Succession

Terminal Authority: Assessing the CCP’s Emerging Crisis of Political Succession

Executive Summary:

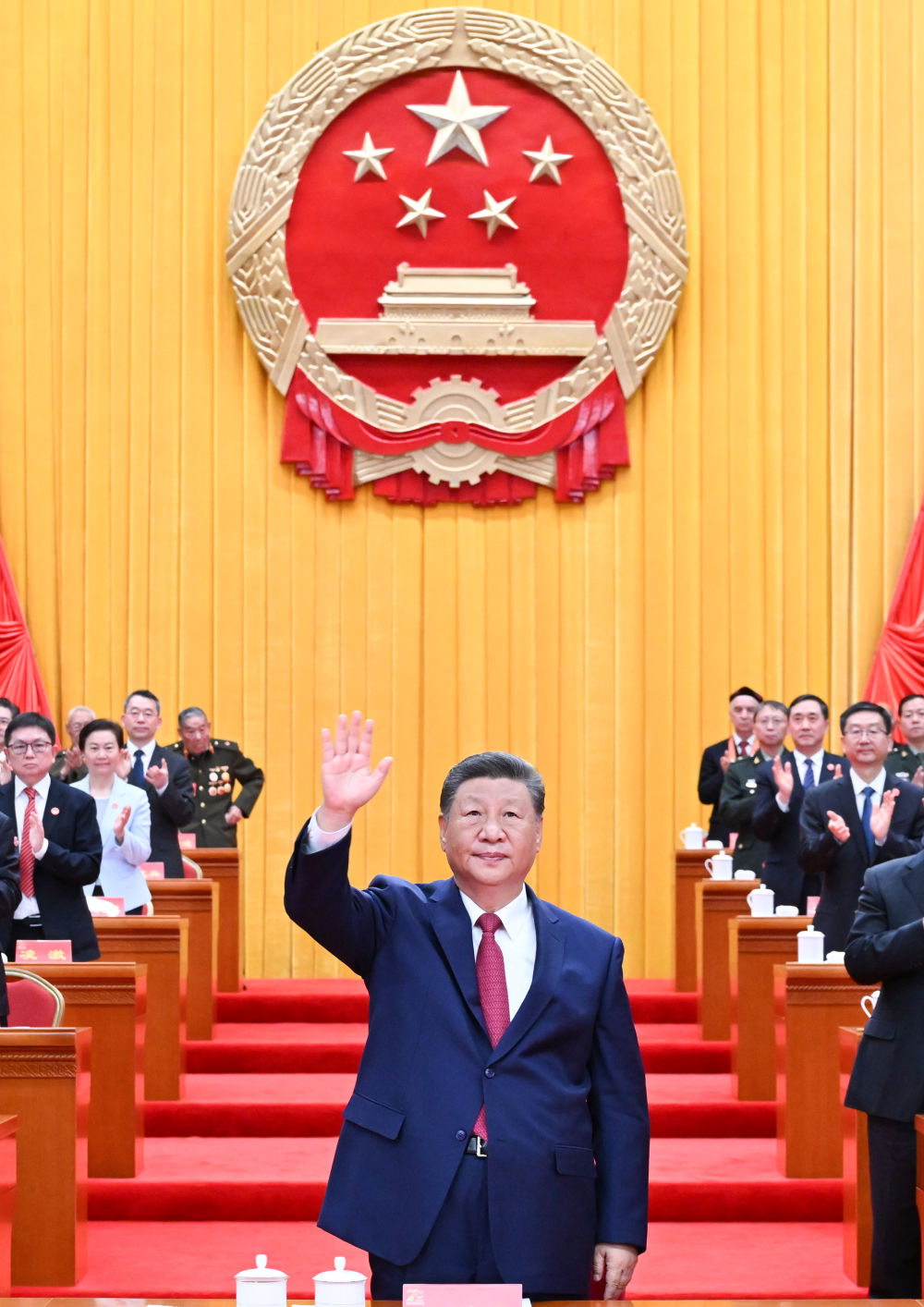

- Xi Jinping continues to dominate the Chinese Party-state system, based on an assessment of evidence from spring and summer 2025. Despite high-level purges, unusual military reshuffles, and persistent rumors of elite dissatisfaction, there is no visible indication that Xi’s personal authority has meaningfully eroded.

- Signs of rebalancing within the military-security apparatus add nuance to this assessment. Structural purges, which have halved the CMC’s size, likely constitute a systematic rebalancing of Xi’s patronage networks. While these actions do not yet amount to an overt power shift, they signal that the outwardly monolithic military-security apparatus Xi once relied upon is now visibly fractured and contested, even as he retains formal authority.

- The possibility of fragmentation and realignment within the elite can no longer be ruled out, though no fixed timetable for such a transition exists. As Xi enters what is effectively the indefinite phase of his tenure, Party elites will increasingly maneuver around the unresolved question of succession. For now, Xi appears capable of dictating terms, but as time goes on, the system will only reduce his power to do so.

Nobody knows what will happen when Xi Jinping passes from the scene. The general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has spent over twelve years at the apex of the Party-state system. This period has been transformational for the People’s Republic of China (PRC), for its place in the world, and for Xi personally. One of the most important changes has been the personalization of the regime under Xi. But it will not last forever. It may not even last beyond the current decade. As he ages, certain questions are becoming more urgent. Is the mortality of the regime tied to the mortality of the man? Or will a successor emerge whom Xi—or the system he leads—can shepherd across the transition?

Central to all of these questions is the nature of political power within the Chinese Party-state. While studied silence from the Party center has left a void filled by rumors, a framework for understanding where power lies in the system and how it functions can provide tentative answers. Such a framework, like the one we provide in this article, should be based on the specific characteristics of the CCP, which mix qualities germane to Leninist political parties with those that are unique products of the CCP’s evolution. Over the course of its history, control over five areas within the CCP has been key to consolidating power. These include the military and the security services—sources of hard power—alongside the nomenklatura/cadre system, the propaganda system, and the Party elites.

Xi Jinping spent the early acts of his tenure cementing his power over institutions and interests in all five of these critical power centers. In his third term, however, and especially over the last year, unusual developments and concerning trends have triggered speculation about Xi’s position. The number of these anomalies has now reached a critical mass and received sufficient attention that they cannot be fully ignored. Rather, by laying them out in context, we attempt to provide a structured approach to thinking about what they entail. We arrive at three possible scenarios for Xi Jinping’s status going forward. We conclude by providing our own judgment on which of the three we think is most likely and why.

The Party’s Structure of Power

“The Party leads everything: the Party itself, the government, the military, and the schools, in the east, west, south, north, and center” (党政军民学,东西南北中,党是领导一切的). This was the most notable addition to the Party Charter made at the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 2017. Other additions included Xi’s eponymous ideological pronouncements, “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era” (习近平新时代中国特色社会主义思想) and “Xi Jinping Thought on Strengthening the Military” (习近平强军思想), as well as the “China Dream of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” (中华民族伟大复兴的中国梦), the “One Belt One Road” (一带一路) initiative, and a new principal contradiction for the Party to resolve (Current Political News, October 24, 2017; People’s Daily, October 28, 2017).

These changes, followed soon after by Xi’s removal of presidential term limits from the state constitution, heralded a new era for the PRC (CSIS, May 8, 2020). They cemented Xi’s vision—as the core of the leadership of the Party—of boldly reorienting the regime to more closely align with its totalitarian roots (Xu, Institutional Genes, August 2025). This vision has been buttressed by a decade-long initiative that “rewires the Party from within and recalibrates the Party’s relationship with the state” via an increasingly potent system of “Party law” (China Journal, March 27, 2024).

Xi’s new era has seen a return to prominence of personalist dictatorship as a primary governing principle within the PRC. As a Leninist party, the CCP often leans toward personalistic rule. Such parties are hierarchical, mobilizational, and task-oriented, so having a single figure to set the agenda by articulating goals for the system to work toward and mobilizing cadres to strive to achieve is helpful (Fewsmith, Rethinking Chinese Politics, June 2021). It helps, too, if the system can find a charismatic leader around whom to construct a cult of personality. This can improve longevity in a regime type that is inherently unstable (Mao and Stalin are outlier cases in this regard—such regimes are usually much more short-lived) (Pennsylvania State University, June 2016; Oxford University DPIR, February 27, 2018).

The personalist dictator has many enemies within the system. The structure of Leninist parties is such that power struggles between individuals and factions are frequent, intense, and brutal; and their outcomes can decisively shape national policy trajectories (World Politics, July 2006). Power struggles, however, rarely lead to the ouster of the top leader. Despite facing at least one significant political crisis per political generation since 1949, the CCP has yet to see a supreme leader irrecoverably taken down. Both Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping weathered serious challenges to their power or even isolation, and both returned to the top. The same has not been true for the Party’s number two. Under Mao, both Liu Shaoqi (刘少奇) and, later, Lin Biao (林彪), were ruthlessly eliminated. In the 1980s, once Deng Xiaoping had secured power and achieved a level of stability, he eventually felt compelled to remove Hu Yaobang (胡耀邦) as General Secretary. He also purged Hu’s replacement, Zhao Ziyang (赵紫阳), who lived out his days under house arrest. An ailing Deng even helped a subsequent general secretary, Jiang Zemin (江泽民), weather a political challenge from President Yang Shangkun (杨尚昆) and his younger brother Yang Baibing (杨白冰), who together wielded significant power over the military. The passing of the CCP’s revolutionary generation did not bring reprieve from political clashes at the top. In the late 1990s, Jiang fell out with his security chief Qiao Shi (乔石), ostensibly over the Falun Gong issue. He was also reluctant to relinquish his position as the chairman of the Central Military Commission after Hu Jintao (胡锦涛) became the Party leader (Xinhua, September 19, 2024).

Xi’s own rise to power and the early years of his tenure were similarly marred by crisis and coercion. The run-up to Xi’s appointment as CCP general secretary led to the later jailing of his main rival, Bo Xilai (薄熙来), and the removal of one of his key backers, Zhou Yongkang (周永康), the Politburo Standing Committee member responsible for internal security. He also removed other officials with ties to Zhou from the internal security leadership. So prevalent has this pattern of senior leadership figures been throughout the Party’s history that, when former premier Li Keqiang (李克强) passed away in October 2023, many suspected foul play. One former Xinhua bureau chief, who dared to call publicly for an investigation into his death, was jailed (China Brief, December 1, 2023; RFA, February 11). But while the Party’s second-in-command has often posed a threat—and in Lin Biao’s case (or that of his family) attempted a coup—individual challengers are not the main source of power struggles that a leader faces.

More frequently, the biggest struggle is between the leader and what might be called the “machine”—the organizations, actors, and networks that constitute the institutional bedrock of the ruling party. In this framing, the “man” and the “machine”—in other words, the leader and the party-state system—maintain a codependent relationship. Effective governance relies on an equilibrium between the two. But the balance is constantly in flux as the context and the dynamics of the relationship evolve over time. At various moments, one or the other might have the upper hand (Jiang, Man versus Machine, June 2024). The “machine” that the supreme leader sits atop is a complicated matrix of various subsystems that interact and overlap in myriad ways. Or, as the Research Center for Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era of the Central Party School explains in an article published in Qiushi, the CCP functions as the operational “axis” (轴心) for a national governance “tixi” system composed of many “xitong” systems (中国特色国家治理体系是由多个系统构成的) that have a “clear hierarchy” (层次清楚) between them (Qiushi, November 28, 2019).

Xi has sought to improve the mechanisms through which this system-of-systems functions. For instance, he emphasized the importance of “strengthening system integration” (强化系统集成) and “adhering to the system concept” (坚持系统观念) in the Decision document that emerged from the Third Plenary Session of the CCP Central Committee in July 2024 (Beijing Daily, March 17). He has done this—along with other centralizing efforts—to enhance his executive power and drive the system in his preferred direction. But the system has frequently resisted, albeit in oblique ways. The phenomenon of officials “lying flat” (躺平), by pursuing superficial compliance or active inaction in response to central policy directions, is one example of such resistance. Another is the various forms of corruption that officials engage in, which can undermine governance institutions. Further evidence of the supreme leader failing to implement his will can be seen in people voting with their feet—fleeing the country, shifting capital and business assets overseas, delaying starting families, or engaging in various forms of contentious politics.

Analyzing the Party-state by considering the constituent systems through which it exerts power—as the Party itself does—can help observers assess where power lies and monitor the leader’s ability to wield it effectively. Such an analysis reveals five systems that matter as the main loci of power, including two hard and three soft. [1] The first and second are the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)—here referred to as the “gun”—and the security and intelligence services—here referred to as the “knife.” Control over the Party’s army has been a constant preoccupation of the CCP, from Mao’s utterance of the oft-repeated aphorism that “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun” (枪杆子里面出政权) to new provisions released by the CMC this week focused on “restoring and promoting the Party and the military’s glorious traditions and fine work styles, and firmly establishing the authority of political work” (恢复和弘扬我党我军光荣传统和优良作风,把政治工作威信牢固立起来) (Party Members Net, December 20, 2023; PLA Daily, July 21). The PLA has frequently saved the Party at key historical junctures, such as restoring order during the Cultural Revolution and suppressing protestors in and around Tiananmen Square in 1989. It also played a vital role in the power transition following Mao’s death and during Deng Xiaoping’s ascension to power. The “knife,” meanwhile, has been no less critical to securing the Party’s power. Mao in particular benefited from his henchmen Zhou Enlai (周恩来) and Kang Sheng (康生), who used domestic intelligence against their opponents. More recently, the politicization of domestic security elements by Bo Xilai and Zhou Yongkang helped to make Bo a competitor to Xi in the leadership transition of 2012.

The three softer elements of CCP power are essential for running the Party’s day-to-day affairs. Of these, the first is the propaganda system, here referred to as the “pen.” Beyond constructing and managing the media and cyberspace, the Propaganda Department controls theory and doctrine, and every long-serving CCP leader has relied on trusted officials to craft his preferred narratives and package his policies within an appropriate framework of communist orthodoxy. The second element is the central Party bureaucracy, or the nomenklatura system, hereafter referred to as the “paper.” Within this system, the General Office of the Central Committee and the Secretariat manage paper flow, while the Organization Department and the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) maintain dossiers, evaluate cadres, and, in the latter’s case, investigate Party officials. The requirement that all meetings be recorded and communicated ensures that leaders do not convene outside the setting of a formal meeting, something that would arouse suspicions of factionalism. The final element is the red families—the “blood.” These consist of the top Party families that were present at the creation of the PRC (essentially those represented at the first CCP Central Committee after 1949). Not only do these individuals possess power and wealth, they also grew up in military and leadership compounds with peers who would rise to similar levels. Family heritage remains a criteria for vetting Party members and deciding who will lead Party institutions. Back in 2012, both Xi and Bo were the sons of Party “Immortals,” and despite having a limited network and little central experience, Xi’s heritage enabled him to win support from important revolutionary families. It also allowed him to take forceful actions against the Party “machine” (Jiang, Man versus Machine, June 2024).

Anomalies Across Five Pillars of Power

Xi’s monopoly on power appears impervious. He retains the three highest-level appointments across the Party-state system—CCP general secretary, chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), and state president. Over more than a decade in power, he has diminished the state, rescinding constraints on his presidency; effected enormous reforms to the military, where he continues to purge high-level officers; and has woven his thoughts and words into the regulatory fabric of the Party, driving his personal agenda and corralling the system to support his objectives. To some, the idea that Xi Jinping’s power might be diminishing seems heretical. From an official perspective within the PRC, the idea is indeed heresy. But a failure to consider the possibility that Xi might be navigating a turbulent environment is a failure of imagination—one that both Xi and the system he bestrides have carefully cultivated.

A recent spate of periodic rumors and speculation allege that Xi Jinping’s red star is waning. Most of these are provably false. For instance, the claim that Xi’s position in central media has declined—as measured by appearances—does not fit with the data (China Media Project, June 26). Similarly, claims that he is embattled do not appear to have affected his schedule, which continues to be filled with chairing meetings and delivering speeches, such as the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission and multiple Politburo study sessions. He has also conducted high-level engagements with foreign leaders, including leading the Central Asia Summit in Astana (June 16–18) and meeting with Brazilian president Lula (May 13), Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov (July 15), and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen (People’s Daily, May 14; June 18; MFA, July 15; July 24). The same remains true for the overall policy trajectory. There have been no signs of reversal in the core political trends that have defined the Party’s evolution under Xi’s rule. If anything, those trends—centralized control, disciplined struggle, and the subordination of institutions to personal authority—have only intensified in 2025. No other figure in the Party or military apparatus approaches anything like Xi’s status.

At the same time, the context of the current moment makes it difficult to dismiss these rumors completely. The main contextual point is the question of succession, which looms ever larger, as it does for any aging autocrat. At 72 years old, Xi is no longer young. Rumors about his health notwithstanding, certain indicators suggest that Xi’s mode of governance has shifted in his third term, which could be related to waning physical stamina. For instance, the frequency of his travel has reduced, with Premier Li Qiang now going overseas more than his general secretary does (China Brief, November 15, 2024). Xi has shown other signs that he is delegating his authority and responsibilities now, too. He is convening meetings of certain central commissions less frequently, or is sending written instructions rather than attending in person (South China Morning Post, August 21, 2023; The Economist, July 20).

Anomalies such as these may be accounted for by a transition in Xi’s leadership style—which does not entail any loss in his authority. Other anomalies, however, do not yield simple explanations. We cannot yet know what the system has not divulged, and any echoes from internal machinations cannot easily be deciphered. But the recent emergence of speculation in both diaspora media and anglophone discourse nevertheless provides an opportunity to reflect critically on the nature of Xi’s power, the way in which power operates throughout the Party-state system, and how to assess the relative rise and fall of its key players (China Brief, July 2).

The Gun

The military is the country’s most formidable bastion of hard power. Xi made consolidating his control over the PLA a priority after taking office, launching an anti-corruption campaign and an unprecedented number of personnel moves and promotions (China Brief, February 4, 2015). Having cemented his command, he has spent the last decade overseeing sweeping and ambitious reforms to the military’s organizational structure and encouraged it to perform an increasingly active series of drills and exercises, most notably around Taiwan.

Xi’s power over the PLA nevertheless has clear limits. He himself has no military credentials to speak of. He also had to make concessions in his efforts at reform, maintaining the predominance of the ground forces within the system and deciding against imposing external checks and balances (China Leadership Monitor, February 27). In addition, he appears to remain heavily reliant on his first CMC vice-chairman, Zhang Youxia (张又侠), who is now 75—unusually old for a CMC member (China Brief, January 17). (He is not the oldest, however. Secretary of the CMC Discipline Inspection Commission, Zhang Shengmin (张升民), is 79. Incidentally, Zhang Shengmin’s position was only added to the CMC in 2017. His retention likely indicates Xi’s trust in him—or at least Xi’s lack of trustworthy alternatives—at a time in which purges in the PLA are ongoing.)

While purges within the PLA have been relatively constant under Xi’s rule, the current state of affairs has departed in some ways from recent history. First, the CMC is currently at its smallest size in decades. Beyond Xi Jinping, Zhang Youxia, and Zhang Shengmin, only Liu Zhenli (刘振立) remains. This follows the dismissal of head of the CMC’s Political Work Department Miao Hua (苗华) in June—one of the highest-level military removals since the Mao era—and the unacknowledged disappearance of He Weidong (何卫东) in March. Vice Admiral Li Hanjun (李汉军) was also stripped of his status in June. Earlier purges include two defense ministers and dozens of commanders across key branches. From 2023 to the present day, the PLA and parts of the military-industrial complex in the PRC have experienced the purging of at least 45 officials, including 17 operational commanders, 8 logistics and procurement officers, and 9 political commissars (see Appendix). The high number of operational commanders purged is unusual—logistics and procurement officers, as well as political commissars, have more opportunities to engage in corruption.

In another anomaly, the Beijing Garrison (中国人民解放军北京卫戍区) has been without a commander since March, when Major General Fu Wenhua (付文化) was transferred to the People’s Armed Police. The current stretch—four months and counting—is the longest the Beijing Garrison has gone without a commander since Major General Wu Lie (吴烈), who left the position in April 1962. (Major General Zeng Mei (曾美) was promoted to commander 19 months later, in November 1963.) The garrison’s political commissar, Zhu Jun (朱军), has been in the role since June 2024, though he was only appointed following an eight-month period during which the role was vacant. Previously, the garrison had never gone without a political commissar for any length of time. Next to the Central Guards Bureau that protects CCP leaders, the Beijing Garrison is the most important PLA unit for coup-proofing the capital.

Other anomalies have been rumored too. These include the suggestion last year that Xi’s wife, the renowned PLA singer Peng Liyuan (彭丽媛), had been appointed to the position of a senior staff member in an organization known as the CMC Cadre Assessment Committee (中央军委干部考评委员会) (China Brief, May 24, 2024). This rumor has not been corroborated, but it aligns with the idea that Xi is low on trust and continues to feel the need to assert his control.

The sheer scale and opacity of the crackdown have raised new questions—not about whether a struggle is underway, but whether Xi is still directing it or instead is responding to it. The loss of Miao Hua and his associated political commissars at lower levels almost certainly reduces Xi’s ability to shape and direct the PLA as an institution, if not as a political player in CCP politics.

The Knife

A defining characteristic of the Xi Jinping era is the steady rise of national security, which now encompasses almost all aspects of governance. This is clear from Xi’s “comprehensive national security concept” (总体国家安全观) and its integration with development (China Brief, May 23). As with the “gun,” Xi has advanced a series of deep reforms to the Ministry of State Security (MSS) that one analyst characterizes as the most important development in the PRC’s civilian intelligence system since its establishment in 1983 (China Brief, November 15, 2024). These efforts have sought both to enhance central Party control over the MSS system and to ensure that the “party center has supreme authority over state security” (国家安全大权在党中央) (Qiushi, April 15, 2024). For much of the MSS’s history, the ministry was decentralized and its leadership chosen, in part, to keep it weak (China Brief, January 14, 2011).

At the top of the MPS, meanwhile, a reshuffle appears to have taken place in recent weeks. In late May, Hu Binchen (胡彬郴) left his role as assistant minister (部长助理) in Beijing to become head of the public security department and vice governor of Jiangsu Province (People’s Daily Online, May 30). Hu, an official with experience working in the PRC embassy in Washington, D.C., and on international police work with the United States, had only served in the role of assistant minister for one year. This suggests that his transfer to Jiangsu could be politically motivated—a theory that is perhaps supported by the subsequent dismissal of two vice ministers (副部长), Chen Siyuan (陈思源) and Sun Maoli (孙茂利), in early July (Ministry of Human Resources, July 9). To replace them, Yang Weilin (杨维林) has been pulled up from the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region to be appointed as a new vice minister (Baidu Baike/杨维林, accessed July 24). Yang has been tied to the Communist Youth League (CYL) faction due to his connections with Bayanqolu (巴音朝鲁), who was in leadership positions within the CYL Central Committee over the period 1993–2001 (Jilin People’s Government, October 29, 2014). The two overlapped in Jilin Province, where Yang worked in multiple roles in the political-legal system while Bayanqolu worked as the Jilin Party Secretary (Department of Public Security of Jilin Province, August 31, 2017; Siping Chang’an Net, January 24, 2019; HKCD, January 23). The CYL faction is closely associated with Hu Jintao’s leadership. Overinterpreting such factional ties is ill-advised, but when viewed alongside these other high-level reshuffles, Yang’s appointment could support an interpretation that the MPS has experienced some political turbulence in recent months. [2]

The knife may be one area where Xi is relatively weaker than he is elsewhere—at least in terms of the duration and depth of his direct influence. When Xi first became general secretary, he faced an internal security apparatus that had been politicized by his opponents and required significant organizational and personnel reforms to neutralize the knife as a political danger (China Brief, June 22, 2012; War on the Rocks, July 18, 2016). Of all the elements, the political-legal apparatus, including the MSS and MPS, was the last to face Xi’s rectification campaigns, which finally arrived in 2020—well into his second term. This was much later than similar efforts to bind the military, propaganda, or central bureaucracy systems (iFeng, July 8, 2020). Even then, only around the 20th Party Congress in 2022 was Xi able to get his people into the leadership roles across the key ministries and the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission (China Leadership Monitor, November 30, 2023).

The Paper

The Party-state bureaucracy continues to be governed by a tightly knit circle of Party elites whose legitimacy and authority are closely tied to Xi Jinping. These include senior figures on the politburo standing committee like Wang Huning (王沪宁), the CCP’s chief ideologue and architect of “Xi Jinping Thought,” Cai Qi (蔡奇), Xi’s longtime chief of staff, Zhao Leji (赵乐际), the head of the CCDI who led past anti-corruption purges, and Ding Xuexiang (丁薛祥), Xi’s former general office director now serving as vice premier. No group that could be seen as a rival faction or figure has surfaced. That said, loyalty remains fluid. For example, some rumors suggest that Cai Qi may be cultivating ties with CMC Vice Chairman Zhang Youxia, who is framed as the most plausible challenger to Xi (YouTube/老灯, June 12). On July 7, state media showed that Cai Qi led the ceremony in Beijing of the 88th anniversary of the beginning of the “entire nation’s war of resistance” (全民族抗战) with Zhang Youxia and other senior CCP officials present, while Xi was in Shanxi paying tribute to the martyrs alone (Xinhua, July 7; People’s Daily, July 7).

Several officials have been removed or transferred from key organs in the bureaucracy in recent months, though none of these changes suggest that Xi is losing his power over the nomenklatura. These have included the unusual switch of Li Ganjie (李干杰), who led the department for just two years, with former director of the United Front Work Department Shi Taifeng (石泰峰). Although this was framed as a lateral transfer, in practical terms this constitutes a demotion for Li (China Brief, April 23). The moves have also included former head of the CCDI’s discipline inspection and supervision office (纪检监察组) Li Gang (李刚), who was expelled from the Party in April on corruption charges (Global Times, April 7). Li Gang and Li Ganjie both allegedly have ties to Chen Xi (陈希)—a former Tsinghua University roommate of Xi Jinping’s and a possible close ally (Aboluwang, October 2, 2024; Nikkei Asia, April 10). It is unclear, however, what the nature of these ties are, or whether Li Gang’s dismissal is in any way connected with Li Ganjie’s transfer. Overall, beyond the unusual switch between Li and Shi, there is little evidence that Xi’s grip on the knife is slipping.

The Pen

The propaganda system is one area in which Xi’s power has remained the strongest. His confidence in this part of the Party-state bureaucracy is perhaps reflected in the lack of senior personnel changes over the last year. His control is also reflected in the frequency of his appearances in state media, including on the front page of the People’s Daily (人民日报) (China Media Project, June 26). In his first term, Xi toured state media organizations, delivering speeches as part of his “Propaganda Thought Work” (宣传思想工作), which emphasizes loyalty to the Party and the importance of guiding public opinion (China Brief, February 23, 2016). These tours also allowed Xi to diminish Liu Yunshun (刘云山), one of Jiang Zemin’s men who headed the Propaganda Department from 2012–2017, laying the groundwork to place his own man in charge (China Brief, February 23, 2016). After sidelining Liu, Xi selected Wang Huning (王沪宁), a member of the Politburo Standing Committee, to oversee propaganda.

Part of Wang’s mission has been to help build a cult of personality around Xi. It is possible that Xi could be dissatisfied with this system for its lack of success in creating such a cult, despite continuous attempts over the last twelve years (China Brief, March 6, 2015). Some analysts observe an emerging cult that emboldens and empowers Xi, making continuous purges feasible (Asia Society, February 26). Others, meanwhile, see the attempts to cultivate an image of Xi as a charismatic and visionary leader as “clumsy” and “counterproductive” (Xu, Institutional Genes, August 2025). Indeed, others still suspect that parts of the system have intentionally leaned into the personality cult as a form of resistance, using excessive and nauseating praise of Xi to remind the public and other elites of the traumatic experience of the Maoist era, thus delegitimizing Xi (Jiang, Man versus Machine, June 2024). Additional evidence of potential backlash against Xi’s burgeoning personality cult emerged in the form of a series of articles in the PLA Daily, published in the second half of 2024. These emphasized the importance of “adhering to collective leadership” (坚持集体领导), which could be seen as pushback to Xi’s governing style (China Brief, March 15).

In recent months, indicators of additional issues within the propaganda system have emerged. In terms of personnel, two officials have been recently purged from the People’s Daily, with another reportedly under investigation. Hu Guo (胡果), the paper’s first female vice president, and Yu Jijun (余继军), a member of the editorial committee, disappeared from the “leadership” section of the paper’s website sometime between December 2024 and June 2025 (People’s Daily, accessed December 18, 2024, accessed June 20; Lianhe Zaobao, June 9). Meanwhile, rumors are circulating that the president of the organization, Yu Shaoliang (于绍良), has been taken away for questioning. This is unconfirmed, however, and his name is still listed on the leadership page (YouTube/@yuege-nanfanglang, June 10). Yu was only promoted to president last September, so his removal would be unusual. Li Muyang, a U.S.-based commentator, argues that his removal could mean Xi Jinping “is in a bad way” (Epoch Times, June 9; Watch China, June 12). Some analysts believe that the removal of Yu Shaoliang, as a full ministerial leader, and Hu Guo, as a vice-ministerial leader, both of whom were mouthpieces for Xi Jinping Thought, could indicate that Xi is losing power (Watch China, June 12). The Propaganda Department has not been entirely without its own issues either. In June 2024, Vice Minister Zhang Jianchun (张建春) was placed under investigation by the CCDI before being indicted in April on suspicion of accepting bribes (CCDI, June 21, 2024; Xinhua, April 18).

Despite these developments and apparent limited success in forging a personality cult, the propaganda system remains widely regarded as one of Xi’s key strongholds. If Xi were involved in a power struggle, the propaganda system probably would be the last place for indicators to appear. Any appearance of such indicators, however, should be a tripwire signaling impending change to the structure of CCP politics.

The Blood

Perhaps the most opaque of all the Party’s power centers, the position of the red families and “princelings” is difficult to discern. In the absence of evidence, rumors of discontent among retired senior CCP officials—and of their alleged efforts to collectively or individually challenge Xi Jinping’s leadership—have circulated since 2017. The latest iteration of these claims surfaced in mid-2023, when reports alleged that three Party elders aligned with Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao (温家宝) criticized Xi’s policies during a closed-door discussion at the annual Beidaihe retreat (China Brief, June 24; The Bureau, June 25). The speculation quickly evolved, with some outlets claiming that Hu, Wen, Li Ruihuan (李瑞环), and Zeng Qinghong (曾庆红) had begun coordinating efforts to unseat Xi. Astonishingly, these rumors claim that the elders had succeeded, with Xi’s resignation said to be inevitable, though these lack credible supporting evidence (YouTube/墙内普通人, June 28). The initial claim that Xi Jinping was criticized during the 2023 Beidaihe retreat originated from a report by Nikkei Asia, which cited an anonymous Party insider. It carries at least a small degree of plausibility. If such a meeting did occur, however, the intent may have been much more benign, such as well-meaning advice from senior figures in the spirit of the “intra-Party democracy” (党内民主) that some retired cadres are still nominally entitled to. All four of the individuals are over 80 years old, and Hu in particular appeared frail and disoriented when he was escorted out of the 20th Party Congress in 2022. This makes it hard to believe they could remain capable of sustained political engagement. Nor do they appear to have any significant political leverage over the key power institutions, especially with the “gun” and the “knife.”

Today’s retired Party elders lack the institutional mechanisms once available to influence policymaking or intra-Party deliberations. The Central Advisory Commission (中央顾问委员会) that existed under Deng Xiaoping provided a formal channel for senior cadres to remain engaged in elite politics, yet no such counterpart exists today (Institute of Party History and Literature, May 18, 2017). Even if that commission served as a polite fiction, Deng’s peers shared his decades-long connection to leaders across the elements of CCP power and could exercise considerable influence outside formal channels. Since coming to power, though, Xi has made it clear that he does not want retired cadres to interfere. A commentary that ran in the People’s Daily in 2015 used the phrase “tea getting cold after people have left” (人走茶凉)—meaning that people cease to care about those no longer in positions of power—and railed against unnamed leaders who “refuse to stay out of major decision-making of their original offices, even after stepping down for many years” (退下多年后,对原单位的重大问题还是不愿撒手) (People’s Daily, August 10, 2015). This directive was widely interpreted as part of Xi’s broader effort to marginalize the influence of elders and enforce his own set of “political rules” (政治规矩) (China Brief, August 18, 2015).

Yet it is worth asking why such rumors—of retired Party elders rising to challenge Xi Jinping—persist, and why they tend to proliferate whenever Xi disappears from public view for an extended period. At the core lies a form of political imagination shared by many PRC citizens, especially among elite circles disillusioned with Xi’s policies and autocratic leadership style. For these individuals, the Jiang-Hu era represents a kind of “golden age”: a time of rapid economic growth, expanding urban wealth, and relatively greater economic freedom for private entrepreneurs—a stark contrast from Xi’s preference for the advance of the state and the retreat of the private sector (国进民退). Within the Party-state system, many officials benefited from a more balanced power structure and limited but meaningful “intra-Party democracy” during the Jiang and Hu administrations. In contrast, Xi’s rule has been marked by strict centralization, “one-man authority” (定于一尊的权威), and prohibitions against expressing dissent toward the central leadership (不得妄议中央). The nostalgia for the Jiang-Hu era, particularly its norms of collective leadership and relative openness, has therefore become a vehicle for passive resistance to Xi’s governance.

This may explain why the protagonists in these anti-Xi rumors are invariably retired Jiang–Hu era leaders, rather than rising political challengers or reform-minded younger officials. From a practical standpoint, a younger challenger would be far more likely to pose a credible threat. Yet popular political imagination tends to favor the symbolic return of a bygone era over the emergence of an unknown alternative. In this sense, such rumors function less as accurate political forecasts and more as expressions of longing for a past that now appears irretrievably lost.

Throughout China’s political history, rumors have often served as tactical instruments for reshaping power structures. In many episodes of dynastic succession and regime transition, political challengers first circulated rumors to test the ground before taking concrete action. In highly repressive environments where open dissent is dangerous, anonymous dissemination of rumors offers a low-risk means of probing whether their content resonates, either among regime insiders or among the broader populace. If the rumor finds traction, its originators may identify potential allies within the system or detect pockets of social discontent that can be mobilized. If the rumor fails to elicit a response, it still serves the purpose of venting frustration and testing the “political temperature” without direct exposure. Although today’s anti-Xi rumors lack the metaphysical dimension of the “Mandate of Heaven” (天命) or “prophetic texts” (谶纬), the logic of their production and dissemination closely mirrors that of historical power struggles: to challenge centralized authority indirectly through anonymous, deniable signals when direct confrontation is not viable.

From this perspective, even if the content of these rumors is implausible, the fact that such narratives circulate at all may indicate undercurrents of discontent beneath the surface of Party unity. Under Xi’s tightly controlled leadership, the CCP presents a highly centralized image of discipline and stability. Yet the persistent circulation of rumors suggests that beneath this facade lie latent political tensions. These tensions are occasionally brought to light by outspoken insiders. For instance, retired Central Party School professor Cai Xia (蔡霞), in a leaked 2020 address at a conference organized by princelings, denounced Xi’s CCP as a “political zombie” (政治僵尸) and described him as a “mafia boss” (黑帮老大) who has turned 90 million Party members into tools for personal power (China Digital Times, June 4, 2020). These undercurrents could resurface at a critical inflection point, such as if Xi, in his later years, is compelled to designate a successor, either publicly or in secret. At that moment, actors currently feigning loyalty may shift their allegiances and coalesce around the successor as a new, semi-autonomous center of power, potentially beyond Xi’s control.

Scenarios

Power struggles are the norm, not the exception, in CCP politics. But uncovering them is a considerable analytical challenge. As Xi ages and the absence of a designated successor becomes more conspicuous, elite actors are inevitably maneuvering around the question of who—or what—comes next. The following three scenarios outline possible paths of political evolution, ordered by degree of disruption.

Scenario 1: Xi Jinping in Charge

In this scenario, Xi remains dominant and above the fray, even as elite competition intensifies beneath him. The leadership refrains from naming a successor, and Politburo Standing Committee members like Wang Huning, Cai Qi, and Zhao Leji continue to serve as loyal executors of Xi’s agenda rather than rivals in waiting. Xi maintains control over key mechanisms of Party governance—particularly the Central Military Commission, the Politburo, and the central commissions that steer policy formation. Party messaging continues to elevate Xi as the Party’s core leader, with ideological campaigns reinforcing his authority. Purges and personnel reshuffles persist, especially in the military and tech sectors, signaling that control is being maintained through disciplinary enforcement. Under this scenario, infighting may intensify, but it remains constrained within the system Xi built, with no alternative power center gaining real traction.

Scenario 2: Xi Jinping Diminished

In this scenario, the Party-military “center” becomes fragmented. Xi’s authority remains intact but is increasingly contested. Elite infighting spills into visible institutional dysfunction, evidenced by prolonged vacancies in key roles, unusual personnel turnover, or divergent policy signals between Party organs. Xi’s close allies, such as Cai Qi or Ding Xuexiang, may be drawn into factional disputes or begin cultivating patronage ties with other factional “mountaintops” (山头) (such as Cai’s rumored alignment with Zhang Youxia). Parallel centers of influence may form around powerful actors in the military, primary economic nodes (e.g. energy), or provincial Party apparatuses. Xi’s ability to dominate central commissions and Politburo processes weakens, and the system reasserts its power through more transactional elite coordination. Purges may become riskier and more destabilizing, as all factions treat them as moments of existential crisis rather than political recalibration. This scenario does not imply a coup or collapse, but it does suggest the re-emergence of real horizontal contestation, breaking the top-down coherence of Xi’s first 13 years in power.

Scenario 3: Xi Jinping Finished

This, the most disruptive and least probable scenario, would see Xi abruptly sidelined, reduced to a figurehead, or removed entirely. Triggers could include a sudden health crisis, an engineered Party plenum to strip Xi of real authority, or a coordinated institutional realignment initiated by top-level officials—most likely from within the CMC or Politburo Standing Committee. Signals for this kind of development would include sharp discontinuities: the rapid elevation of a successor figure, a dramatic shift in state media tone, or sweeping changes in policy language disavowing aspects of Xi’s governance model. Key allies such as Wang Huning or Ding Xuexiang would likely disappear from public view, replaced by more conciliatory or transitional technocrats. Though unlikely, this scenario cannot be entirely ruled out, especially given the historical precedents of sudden shifts at moments of perceived overreach or vulnerability (e.g. Mao’s death and subsequent fall of the Gang of Four). The decisive feature would be that the system no longer merely “contains” struggle—but that struggle spills over into open political conflict.

Conclusion

We assess that “Scenario 1”—that is, Xi Jinping continues to dominate—remains the most likely description of the current political status quo, based on the weight of evidence from spring and summer 2025. If a challenge had emerged over succession-related issues, the state of the economy, and the U.S.-PRC trade war, then Xi successfully dealt with that challenge by the time of publication.

Despite high-level purges, unusual military reshuffles, and persistent rumors of elite dissatisfaction, there is no visible indication that Xi’s personal authority has meaningfully eroded. He continues to chair Politburo meetings, oversee the work of key commissions, and dominate state media coverage. Xi’s closest allies—Wang Huning, Cai Qi, Zhao Leji, and Ding Xuexiang—remain firmly embedded across the Party’s institutional core. No rival faction or potential successor has emerged with the political standing or organizational base to challenge him. While signs of elite maneuvering suggest the system is becoming more fluid, it still functions through the structures and personnel Xi built, not in defiance of them.

A note of caution is warranted, however. Recent developments also indicate signs of rebalancing within the military-security apparatus, adding nuance to our assessment of a still-intact Xi power center. June’s Politburo meeting, which reviewed new internal regulations for Party decision-making bodies, spoke to growing institutional awareness of the need to formalize procedures and curb unchecked command, even as it underscored Xi-era priorities (China Brief, July 2). Simultaneously, sweeping turnover in the military and security services has taken shape this year. June 2025 alone saw Admiral Miao Hua—the head of the CMC’s Political Work Department and once a close Xi appointee—removed from the Central Military Commission and expelled from the NPC, alongside the sidelining of Vice Admiral Li Hanjun and the disappearance of General He Weidong from public duties. The structural purges, which have halved the CMC’s size, are widely understood not only as anti-corruption efforts but also as a systematic rebalancing of Xi’s patronage networks. While these actions do not yet amount to an overt power shift, they signal that the outwardly monolithic military-security apparatus Xi once relied upon is now visibly fractured and contested, even as he retains formal authority.

Early signs of tension suggest that a transition to “Scenario 2”—fragmentation and realignment within the elite—can no longer be ruled out. There is no fixed timetable for such transitions. Scenario 2 may endure for years, or it could quickly spill into open power struggle if elite competition spirals. Although the Party once developed norms to manage succession and prevent destabilizing uncertainty, Xi’s dismantling of those rules has reintroduced precisely the kinds of internal tensions those norms were meant to contain. If anything, those tensions are likely to intensify. As Xi enters what is effectively the indefinite phase of his tenure, Party elites will increasingly maneuver around the unresolved question of succession. Biological fact ensures that the core will not hold forever. For now, Xi appears capable of dictating terms, but as time goes on, the system will only reduce his power to do so.