Russia’s Interests in Belarus: Ends and Means (Part Two)

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 17 Issue: 145

By:

*To read Part One, please click here.

Regime change via constitutional reform is Moscow’s chosen avenue toward its goal in Belarus: turning the country into a satellite of Russia, stopping short of outright incorporation (see Part One in EDM, October 15).

At this stage, however, Moscow finds itself in the unforeseen position of pursuing that goal without local Belarusian allies. Notwithstanding the country’s friendly disposition toward Russia at all levels of society, and the weak sense of national differentiation from Russia (again, uniquely Belarusian features), Russia currently lacks any identifiable bridgeheads or footholds within Belarus’s governmental nomenklatura, economic interest groups, the intelligentsia, or civil society associations. The authoritarian President Alyaksandr Lukashenka effectively foreclosed any such openings to Russia in Belarus during his long rule. The authorities have also impeded “Russian World” (“Russkiy Mir”)–oriented activities at the grass roots level, as exemplified by activists Elvira Mirsalimova and Siarhei Tsikhanouski (prior to his sudden rise from obscurity last year) or the just-retired Russophile politician Siarhei Gaidukevich, forever nailed to the reserve bench.

Moreover, the absence of a multi-party system and parliamentary government in Belarus meant that Moscow could not use pro-Russia parties to dominate this otherwise Russia-friendly country. This is why Russia (itself an autocracy) now favors a Belarusian constitutional reform that would create a parliamentary republic with a multi-party system, open to Russian manipulation.

The presidential candidacies of Valery Tsepkalo, Viktar Babarika and Siarhei Tsikhanouski were not designed to win the election but, in all probability, to morph into leaders of political organizations or movements following the presidential election, with a view to destabilizing Lukashenka in his sixth term. Indeed, in the election’s aftermath, Babarika’s team announced the launch of a political party under his leadership; his own video-recorded announcement was dated in June, and his team duly aired it after the August election, by which time Babarika and Tsikhanouski were in jail and Tsepkalo abroad. Tsikhanouski’s short-lived campaign (upon his arrest, his wife, Sviatlana, stepped in to run in his place) also hinted at a post-election movement. Moscow’s plans for post-election Belarus in all probability envisaged a controlled, calibrated instability—Moscow’s tried-and-tested method.

Unexpectedly to all concerned, however, Lukashenka’s blunders (exaggerating his victory margin over the runner-up, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, and then employing disproportionate force against protesters) triggered massive instability beyond any actor’s control, including the Coordination Council hastily formed by the former candidates’ teams. The Coordination Council found itself catapulted to the top of a popular movement with the optics of a “color revolution,” framed as such both by friendly international media and by hostile Belarusian authorities. This turn of events canceled any utility value of the three former candidates and the Coordination Council as Moscow’s potential allies. Moscow could not align with a “color”-type movement against established authority in a neighboring country. The Coordination Council, moreover, could not control the spontaneous protests and was, therefore, useless to Moscow from that standpoint also. Consequently, Moscow quickly distanced itself from this opposition body (see EDM, September 10, 16, 30, October 1, 7, 8).

Lacking any identifiable Belarusian allies at this stage, Russia is undoubtedly casting about to recruit groups and individual personalities as allies or fellow-travelers (see EDM, October 15). One early possibility is Andrei Savinykh, the chair of the international affairs commission of Belarus’s House of Representatives (lower house of parliament), now demonstratively positioning himself in favor of closer ties with Russia. He is said to aim at replacing the incumbent minister of foreign affairs, Uladzimir Makei, an architect—alongside Lukashenka himself—of Belarus’s normalization of relations with the West prior to these events. Any such replacement would be seen as an instance of Moscow prevailing over Lukashenka. For now, as always, Lukashenka stands in the way of Russia’s recruitment of allies and fellow-travelers, as long as he remains in control. If, however, perceptions take hold that Russia is gaining the upper hand on Lukashenka, there would be no shortage of Belarusian groups and personalities bandwagoning with Moscow and facilitating its satellization of Belarus.

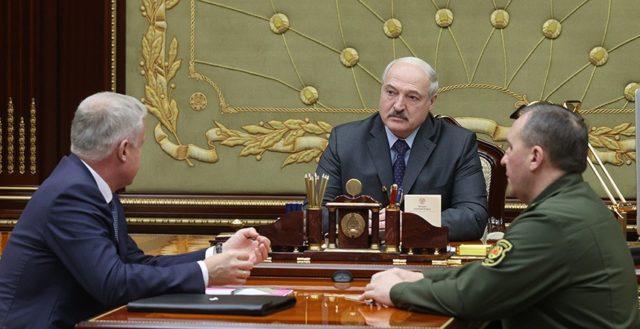

Moscow’s current priority is to use Lukashenka for stabilizing the situation and formally shepherding the constitutional reform, before easing him out through that same constitutional reform. This necessitates tiding Lukashenka’s government over a transitional period with its economic and political challenges. Moscow would not—and probably cannot—move openly toward satellization of Belarus as long as Lukashenka remains in control. For his part, Lukashenka is gaining time and will try to shape the transition process in accordance with Belarusian, not Russian views of Belarus’s interests. Minsk’s overarching goal remains that of preserving real sovereignty as against satellization.

Russia’s interests in Belarus at this stage may be categorized as status quo–oriented interests and those going beyond the status quo, the latter category clearly prevailing.

In the economic sphere, Russia’s status quo–oriented interests include: reimbursement by Belarus of its debt arrears to Russia (even at the cost of Russian refinancing of Belarusian past debt, as agreed by Presidents Lukashenka and Vladimir Putin in Sochi, on September 14); unperturbed transit of Russian oil and natural gas via Belarus to European consumer countries (Gazprom’s latest note to its Eurobond creditors cautioned them about a hypothetical force majeure on the Yamal gas pipeline via Belarus to Poland and onward to Germany—TASS, October 6); and continuing deliveries of Belarusian industrial products to Russia via government-level as well as oblast-level contracts, a raft of which were signed at the recent Forum of Regions in Minsk (BelTA, September 29).

Beyond the status quo in the economic sphere, the Russian government and associated industrial groups undoubtedly envisage takeovers of flagship Belarusian industrial plants, the foundation of Belarus’s economy and export revenue generation. This could be attempted either by Russian business directly or in partnership with local Belarusian counterparts, yet to be identified. This could lay the foundation for an economic and political Russian clientele, which Lukashenka’s government and local managerial class has never accepted in Belarus thus far.