PRC Fertilizer Export Controls Provoke Derisking Abroad

Publication: China Brief Volume: 24 Issue: 19

By:

Executive Summary:

- In June 2024, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) introduced additional restrictions on fertilizer exports, sharply reducing urea exports by 83 percent compared to the previous year. This move aims to stabilize domestic prices and safeguard food security, but has disrupted global fertilizer supplies, prompting countries like India and South Korea to seek alternative suppliers.

- The PRC’s export controls exacerbate an already strained global fertilizer market, which has been impacted by geopolitical tensions, including sanctions on Russia and Belarus, and logistical challenges like disrupted shipping routes. These issues have increased global food security risks, making stable fertilizer supplies a priority in international forums like the G7.

- PRC regulations are transforming its fertilizer industry to reduce carbon emissions and enhance sustainability. This has led to a reduction in overall fertilizer production, though PRC firms continue to invest in research and development to increase efficiency. Strategic overseas investments in fertilizer production, such as in India and Zambia, also reflect the PRC’s commitment to diversifying supply and reducing environmental impact.

- As the PRC reduces its fertilizer exports and focuses on self-sufficiency, countries are diversifying their fertilizer sources. Regions such as Africa, West Asia, and Russia are expected to increase fertilizer production, reshaping the global market and enhancing resilience in agricultural supply chains amid ongoing uncertainties.

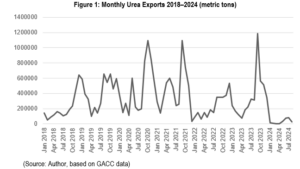

In June 2024, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) introduced fresh restrictions on its fertilizer exports, impacting global food and fertilizer supply (Bloomberg, June 24, Sina.com.cn, July 12). PRC Customs data show that urea fertilizer exports, which have been particularly low all year, dropped sharply following the imposition of controls. Only 105,000 metric tons were exported in July and August, down from 637,000 metric tons in the same period last year (General Administration of the PRC [GACC], accessed October 1). Urea exports are seasonal and usually increase in August and peak in September. The government’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) has taken the decision to restrict exports several times since 2021 to stabilize domestic prices and safeguard the country’s domestic food security (NDRC, July 30, 2021; GACC, October 11 2021; Reuters, September 8, 2023).

The PRC plays an outsized role in the global fertilizer market. In 2023, it accounted for 24 percent of worldwide consumption and 75 percent in East Asia (International Fertilizer Association [IFA], August 20). This means that the PRC’s decisions as a key producer of urea and phosphate-based fertilizer can have a major impact on international trade. As a result, many of its Asian trade partners—including South Korea and India—have reconsidered their reliance on PRC fertilizers, turning instead to alternative suppliers (Business Korea, September 11; Reuters, December 18, 2023).

Geopolitical Risks Have Enhanced Food Security Focus

The PRC’s export controls have been introduced during a period in which the global fertilizer market is increasingly strained by a host of geopolitical and logistical issues. The war in Ukraine has had a profound impact, as Russia and Belarus, two key exporters of fertilizers as well as the oil and gas that is essential for energy-intensive fertilizer production, have faced sanctions and disrupted export routes (IFA, August 20). Global shipping has also been hampered by conflict in the Red Sea and low water levels in the Panama Canal, making it increasingly difficult for countries to secure reliable fertilizer supplies (IFA, August 20; IFPRI, March 21). [1]

Stable fertilizer supply has been prominent in several international policy discussions, as has broader food security. Both were on the agenda of the two most recent G7 summits, held in Italy and Japan, indicating the importance G7 leaders accord to the critical role fertilizers play in maintaining global agricultural productivity (G7, June 14; G7, May 20 2023). While some of these issues have been partially resolved in recent months, traders remain wary due to elevated risks and rising insurance costs (IFA, August 20).

The PRC faces growing domestic challenges to its food security, despite its substantial food reserves. Soil degradation, pollution, and issues with freshwater supplies have contributed to a decline in arable land, which shrank to 1.28 million square kilometers by 2019, a nearly 6 percent decrease from 2009 (China Brief, March 2, 2017; Reuters, August 27, 2021; China Brief, January 19). Although the trend has slowed in recent years, the PRC has intensified its focus on achieving grain self-sufficiency by enacting a new food security law (Gov.cn, June 25, 2023; Gov.cn, December 29, 2023). The law requires local governments to include food security in their economic and development plans, which will increase efforts to bolster food production and grain insurance cover for farmers to protect their income. This clarifies the logic behind the NDRC’s export controls, as the availability of fertilizer will remain vital to improving the PRC’s food security.

Recognizing the need for stability of supply, the PRC has implemented measures to ensure reliable access to fertilizers (NDRC August 22, 2022). Since the ’00s, the government has maintained a strategic fertilizer reserve, recognizing its importance by referring to it in official documents as the “food” of grain (化肥是粮食的 “粮食”). To support stable production, supply, distribution, and pricing, the government issues guarantees at the start of each year (NDRC, February 6). These guarantees call on local governments to ensure the supply of necessary electricity and gas, as well as logistical support to facilitate fertilizer production and delivery.

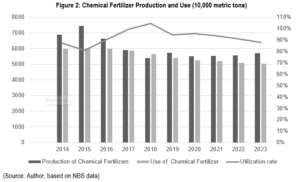

Maintaining a level of self-sufficiency and affordability has been a key priority, but the PRC has also actively pursued policies to increase efficiency and curb the overuse of fertilizers, particularly nitrogen. This is done to improve the sustainability of the domestic agricultural sector. In 2015, the PRC committed to an “Action Plan for Zero Growth in Fertilizer Use by 2020” (Ministry of Agriculture [MOA], May 5, 2015). Between 2014 and 2021, the PRC steadily reduced its nitrogen fertilizer use by an average of 4 percent annually, with total use of chemical fertilizer dropping from around 60.2 million metric tons in 2015 to 50.2 million metric tons in 2023, according to data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) (IFA, August 20; NBS, accessed October 1). [2] During this time, overall chemical fertilizer production also decreased from 70.3 million tons to 57.1 million tons (NBS, accessed October 1). [3] Despite these reductions, the PRC has consistently maintained a slight surplus in production of chemical fertilizers. Between 2014 and 2023, the PRC used 93 percent of its supply on average, exporting the excess.

PRC Regulations Push Production Overseas

The primary motivations for the PRC’s strategy of placing export controls on fertilizer are short-term domestic concerns. Despite the surplus in its fertilizer reserves, the government aims to stabilize domestic fertilizer availability and, consequently, keep food prices in check amid rising global costs. Beijing’s dedication to protecting its food supply and ensuring affordability—an essential component of its national security strategy—reflects its commitment to guaranteeing price stability for domestic consumers and signals its reliability in addressing economic challenges (Gov.cn, April 8, 2021). The sustainability of the PRC fertilizer industry in the medium and long terms is another motivating factor. The domestic industry is currently undergoing a significant transformation. This has manifested in substantial government investments in research and development to promote more efficient fertilizer use. Production in the PRC is set to undergo significant changes as part of a long-term strategy to reduce carbon emissions.

Fertilizer production currently depends heavily on coal and gas. This is particularly the case for nitrogen, where the PRC is a global leader. Electricity shortages in recent years have even led to the shutting down of fertilizer production and other energy-intensive sectors, as the government has been forced to set priorities for energy distribution (Reuters, September 9, 2021; thepaper.cn, August 18, 2022; Caixin, August 24, 2022; Xinhua, July 3, 2023; Asia Nikkei, August 29). Shortages are seasonal, typically occurring when capacity at hydropower plants is reduced due to extreme heat and drought, but they still contribute to unreliable conditions for fertilizer production. The impact of electricity shortages may fall in the future as the PRC continues to enhance its grid capacity and energy storage solutions, but for now, it remains a concerning issue for the country’s leadership.

Several policies have been designed to shift the sector away from its reliance on fossil fuels. For instance, the “Action Plan for Carbon Dioxide Peaking Before 2030” and related industry-specific initiatives emphasize energy efficiency and innovation in chemical processes, which indirectly impact fertilizer production by imposing stricter environmental regulations. These policies also aim to “curb the blind development of high-energy-consuming and high-emissions projects (坚决遏制高耗能高排放项目盲目发展)” (Xinhua, October 24, 2021). The “1+N” framework is an indicator of additional regulations on fertilizer production, which is highly energy intensive. It outlines carbon reduction measures for all major emitting sectors, including agriculture and petrochemicals (NDRC, September 23, 2022).

While additional regulation may accelerate the transition toward more sustainable and efficient practices within the PRC, it may have also incentivized Chinese companies to invest outside the country to diversify production and supply. For example, in recent years, China National Chemical Engineering (中国化学工程; CNCEC) has invested $1.1 billion in Talcher Fertilizer in India (2019) and $460 million in United Capital Fertilizer in Zambia (2022) (AEI, July). In 2021, a subsidiary of the PRC company Asia-Potash International announced a $4.1 billion investment in a potash mining venture in Laos (AEI, July; RFA, June 15). [4] Fertilizer investments abroad could supply increased agricultural investments (MOA, June 20). Demand for fertilizer for agriculture projects overseas in which PRC entities are involved is likely to continue to grow, following the recent Forum on China-Africa Cooperation and the BRICS Agricultural Ministers Meeting (Ministry of Foreign Affairs [MFA], September 5; MOA, June 30). PRC companies shifting production to less regulated markets overseas could diversify production, secure supply, and still support the PRC’s decarbonization efforts, without necessarily reducing their reliance on fossil fuels.

The PRC’s domestic commitment to minimizing its environmental impact and meeting its carbon emissions goals while maintaining the productivity and self-sufficiency of its agricultural sector has additional implications for the global fertilizer market. As the PRC is expected to gradually decrease fertilizer production while ensuring sufficient domestic supply, the exports of its excess production are carefully managed to shield domestic prices from global instability. Other nations are therefore being forced to reconsider their dependence on fertilizers from the PRC. This trend is particularly evident in Asia, where countries such as South Korea, India, and Malaysia have traditionally relied heavily on the PRC to meet their agricultural input needs. The shift away from overreliance on the PRC, coupled with global market changes, is unlocking new capacities in other regions. For example, nitrogen use is expected to be replaced by new ammonia capacity emerging in Russia, Uzbekistan, the United States, Egypt, Nigeria, Iran, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, India, and Australia (IFA, August 20). Similarly, phosphate production is expected to grow by 11 percent, with Africa and West Asia leading this expansion. Overall, the restructuring of the fertilizer landscape reflects strategic moves toward greater resilience and sustainability in global agricultural supply chains.

Conclusion

The PRC’s strategy for its fertilizer industry focuses on stabilizing domestic prices and agricultural output while reducing long-term carbon emissions. Although food security remains a priority, the PRC is set to gradually reduce its fertilizer use and production, maintaining surplus capacity to handle future uncertainties. As one of the world’s largest agricultural players, the PRC’s focus on self-sufficiency in fertilizer production reduces the risk of major disruptions for others, such as sudden surges in domestic demand draining global supply. By prioritizing domestic supply, the PRC minimizes its dependence on foreign sources, enhancing its ability to manage supply fluctuations arising from geopolitical tensions or market volatility. This makes it a more reliable and predictable player for international stakeholders.

The continued imposition of export restrictions when necessary to stabilize domestic prices adds to global market uncertainty, however. Consequently, the global fertilizer landscape is beginning to undergo changes as countries seek alternative suppliers.

Notes

[1] The Israel-Hamas conflict and escalating tensions in the Middle East have resulted in shipping delays in the Red Sea, fueling worries about possible price increases.

[2] See Indicator “农用化肥施用折纯量(万吨)” / of “Effective Component of Chemical Fertilizer (10,000 tons)” under “农业” / “Agriculture” and “有效灌溉面积、化肥施用量 (…)” / “Irrigated Area, Consumption of Chemical Fertilizer (…)” in annual data.

[3] See indicator “农用氮、磷、钾化肥产量 (万吨)” / “Output of Industrial Products, Chemical Fertilizers (10,000 tons)” under “工业” / “Industry” and “工业产品产量” / “Output of Industrial Products” in annual data.

[4] The AEI data is based on 2024 Q2 numbers. These are not currently publicly available and were acquired through a request by the author.