DeepSeek Use in PRC Military and Public Security Systems

By:

Executive Summary:

- Military procurement documents show that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is adopting homegrown artificial intelligence (AI) systems like DeepSeek to accelerate its shift toward “intelligentized warfare.”

- PLA experts describe DeepSeek not as a single product but as an evolving system architecture. They envision integrating this system across the PLA’s entire command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) chain.

- Debate is ongoing as to DeepSeek’s utility for PLA purposes. Some powerful institutions back its deployment, while others remain sceptical.

- Public security and policing are two areas also exploring the use of DeepSeek, especially for enhancing surveillance and data analysis, as well as for assisting with report writing and other processes.

- The model’s success is framed as both a technological breakthrough and a political achievement in “algorithmic sovereignty.”

On October 21, the Chinese artificial intelligence (AI) company DeepSeek (深度求索) announced the release of a new tool to converts large text datasets into compact image-based formats: DeepSeek-OCR (DeepSeek, October 21). While not the long-awaited R2 large language model (LLM), the firm’s latest release shows that it is continuing to innovate, even as it moves deeper into the orbit of the Party-state. DeepSeek’s success, however, has brought it to the attention of not just the government in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), but also the military.

A procurement platform run by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) shows that a number of defense companies have won contracts to develop AI tools for the Chinese armed forces. Across the past six months, dozens of distinct procurement documents have explicitly called for tools based on AI models created by DeepSeek. Although the number of procurement notices for military AI are relatively small (the platform posts around 25,000 notices every day), the focus on DeepSeek in the notices that are publicly available is still significant.

DeepSeek’s adoption by the PLA and, to a lesser extent, in the public security domain, is evident beyond this dataset. Research published by military institutions frequently discusses how DeepSeek and other models could be deployed across a range of application scenarios. In some cases, pilots of these systems are already underway. DeepSeek’s models have also been deployed widely across the public and private sectors over the course of 2025, and have become increasingly aligned with state interests (China Brief, March 28, April 25). Given the PRC’s policy of military-civil fusion, PLA deployment of DeepSeek was only ever a matter of time.

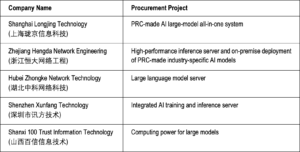

Private Firms Top PLA Procurement of DeepSeek Tools

Private companies, rather than state-owned enterprises (SOEs), have won a majority of contracts to build DeepSeek-integrated tools for the PLA. This could reflect the greater capacity of private firms to respond quickly to shifting market dynamics. SOEs tend to be more cautious and slower to adapt to technological advances (Zhou et al., 2017).

Among these, Shanxi 100 Trust Information Technology (100 Trust; 山西百信信息技术) has won one of the biggest PLA contracts. The company, based in a less prosperous coal-mining region in North China, is the only wholly privately-owned firm included in the PRC’s “information technology application innovation” (信息技术应用创新/“信创”) framework. This framework was created by the China Electronics Standardization Association (CESA; 中国电子工业标准化技术协会/中电标协) to promote the domestic production of information technology products, software, and infrastructure, and to reduce reliance on foreign systems. The company also is eligible to work on classified projects, enabling it to compete with SOEs for military contracts (China News, August 25, 2023; Sohu News, August 1). On its product page, 100 Trust highlights “domestically produced core components” (核心部件国产化) as a key selling point. Its computing infrastructure (算力底座) is based primarily on Huawei’s Kunpeng (鲲鹏) processors and Ascend (昇腾) AI chips. It also has large-scale contracts with state-owned finance firms for domestically produced hardware (Zhiliao Bidding Information).

A significant share of the company’s revenues appear to come from defense contracts worth tens of millions of renminbi. These contracts, all for AI hardware, have been procured by the PLA and other defense-related entities such as the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC; 中国航天科技集团). (CASC operates the Taiyuan Satellite Launch Center, which is also in Shanxi (CASC, accessed October 10).) This suggests that demand for domestically produced AI hardware in the PRC’s defense sector is already substantial. The awarding of high-value military procurement orders to a privately-owned enterprise conversely suggests that traditional suppliers are unable to meet this demand.

Table 1: Key Private Companies Awarded PLA Procurement Contracts on DeepSeek

Deep Support for DeepSeek Integration

The PLA’s use of DeepSeek is part of a push to anchor the next phase of “intelligentized warfare” (智能化战争) on domestically controlled, low-cost AI infrastructure. Across official and academic publications, PLA experts describe DeepSeek not as a single product but as an evolving system architecture that combines a large-scale reasoning core with modular and domain-specific layers. They envision integrating this system across the PLA’s entire command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) chain.

PLA researchers credit DeepSeek with reducing the need for vast amounts of computing power, allowing advanced reasoning functions to run on Ascend and Kirin processors that are less advanced than cutting edge alternatives. This indigenization is framed as a breakthrough in technological sovereignty, reducing dependence on Western supply chains and enabling widespread AI deployment throughout the military apparatus.

Benchmarks from the National University of Defense Technology (NUDT; 国防科技大学)—a military institution—and related institutes make impressive claims about the abilities of DeepSeek models. According to one paper, DeepSeek’s optimized architecture can reduce energy consumption during training runs by roughly 40 percent compared with GPT-4-class systems while maintaining equivalent inference accuracy. [1] These capabilities are described as essential for edge-level deployment—that is, running AI models close to where data is generated rather than depending on centralized cloud or data center infrastructures. This is critical for continuing functionality in environments where platforms lose connection, for instance due to electronic jamming. Other studies have found similar results. DeepSeek uses a smart “attention-pruning” (注意力权重剪裁) system that helps it focus only on the most important information as situations change on the battlefield. This makes it faster, as it involves less work. Its smaller size—about one-eighth of GPT-4—means it can run on smaller platforms, such as drones. [2]

DeepSeek is well-suited for use cases such as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), autonomous surface vessels, and forward fire-control nodes where limited power and communications bandwidth have historically restricted AI use. According to NUDT experts, it is particularly useful for electronic warfare. DeepSeek can integrate radar, satellite, and UAV inputs to deliver real-time electromagnetic awareness and actionable insights, which allows commanders to adjust tactics and deploy countermeasures within much shorter timeframes than if relying on other technologies. [3]

The PLA’s adoption of DeepSeek has the backing of critical groups within the system. Established defense research organizations with expertise in weapons design, aircraft and unmanned systems, and groups experienced in supercomputing and mission-oriented AI have advocated for its deployment. These include the Chengdu Aircraft Design Research Institute (CADI; 成都飞机设计研究所), which is under the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC; 中航工业), and groups affiliated with NUDT. Experts affiliated with each of these institutions have authored articles in support of DeepSeek’s adoption. [4]

Top engineers are already using the technology. Earlier this year, the director of AVIC’s Shenyang Aircraft Design Institute Science and Technology Committee, who was involved in the development of the PLA’s J-15 and J-35 fighter jets, said that his team was using DeepSeek, which he praised for its potential to provide new methods for aeronautical research (China News, May 2). This kind of support matters rhetorically inside PLA decision cycles. It lets proponents claim both technical rigor and operational relevance when recommending where and how to field DeepSeek variants.

These same institutions typically remain cautious, noting that DeepSeek’s utility is predicated on its ability to provide meaningful operational leverage. This means that its claimed cost, latency, and interpretability benefits must survive PLA-grade verification and should be paired with oversight measures that preserve human authority and system resilience. Some analysts expand on these concerns, acknowledging structural weaknesses and unresolved risks in DeepSeek models. Different models are suited to different application scenarios. The enormous scale of R1, for instance, precludes field deployment of small autonomous platforms, according to experts from the PLA Army Artillery and Air Defense Academy (陆军炮兵防空兵学院). The more compact V3 variant is better suited for such scenarios, but has inferior depth of reasoning skills and sometimes generates unstable or high-risk tactical outputs, such as over-aggressive target assignments. Evaluations from defense research institutes note latency fluctuations, limited reproducibility under network stress, and small-sample testing that undermines statistical confidence. [5]

Other analysts fear that the open-source nature of parts of the ecosystem could lead to problems, such as code exposure, adversarial manipulation, and potential data leaks. As with all large models, reliance on automated reasoning introduces the risk of “black-box” decision chains that could erode human oversight and complicate accountability in lethal operations. Proponents of broad-based deployment of DeepSeek recommend a three-layer regime to ensure model security in response. This would include federated verification, watermark tracing, and multifactor authentication. [6]

For some PLA theorists, these drawbacks do not diminish DeepSeek’s significance. They instead define the contours of a managed transformation. The PLA increasingly treats DeepSeek as both a technological accelerator and a doctrinal experiment. Its strengths, such as computational efficiency, domestic hardware integration, and cross-domain reasoning, align with a push for resilient, self-reliant combat networks. Its shortcomings highlight the persistent need for rigorous testing and layered human-in-the-loop control.

AI-Backed Public Security, Policing, and Surveillance

Beyond the military, the PRC’s public security and policing sector is also embracing DeepSeek, embedding its multimodal capabilities into video surveillance systems to analyze faces, vehicles, and crowd behavior in real time. Akin to a “Minority Report”–style of preemptive control, this is transforming monitoring from passive data collection into proactive risk identification and anomaly prediction (China Brief, December 6, 2024; Li, 2025). [7] Police are also piloting DeepSeek as a tool to integrate case data, generate incident reports, and provide decision support to officers on the ground, reducing reliance on manpower while promising greater efficiency (Liu and He, 2025). [8] Most of these applications are still in their pilot stages. Local public security bureaus continue to be extraordinarily labor-intensive, relying heavily on manpower for daily operations. DeepSeek is mostly used for drafting documents and other basic tasks (Pei, 2024). [9]

Public security literature also frames DeepSeek as a tool for intelligence-led governance. One article praises its ability to identify emerging security hotspots by integrating and analyzing data on traffic flows, online behavior, and demographic information. This is a key part of a growing shift in police work from post-incident response to pre-emptive prevention (China Brief, December 6, 2024; Li, 2025). [10] Official discourse further elevates DeepSeek as critical to “new-type public security combat power” (新质公安战斗力). An article from the Journal of Guangzhou Police College, for instance, describes DeepSeek as an institutionalized instrument under the CCP’s total national security framework to strengthen data-driven policing and stability maintenance (Fu and Cheng, 2025). [11] PRC sources acknowledge concerns over data security, algorithmic bias, and transparency, but the broader trajectory is clear. DeepSeek is being localized and integrated into the country’s public security and policing systems, enhancing law enforcement and supporting regime stability.

Conclusion

Beijing’s adoption of DeepSeek across the military and public security sectors is part of a broader convergence between military modernization and techno-nationalist self-reliance. For a state focused on AI applications and diffusion, open-source systems fit naturally into its strategy. In Beijing’s hands, open-source technologies become an instrument of fostering a dynamic domestic ecosystem and projecting influence over international standards. Adoption of DeepSeek remains nascent and much of the technology continues to evolve. PLA experts are not uncritically supportive of DeepSeek’s adoption. Some continue to warn that DeepSeek also introduce new risks. Structural hurdles like limited compute and training chips await resolution (Baidu, September 15; Bilibili, October 10). But the direction of travel is clear, as the PRC now treats AI as critical infrastructure that is essential for national strength.

The Party-state’s deployment of DeepSeek in military systems poses a challenge to the world. Without norms, safeguards and deterrence, AI models will continue to be stronger and exploited by Beijing to support the emergence of an intelligentized security state that fuses data governance with combat readiness under a single logic of computational sovereignty.

Notes

[1] 李为 [Li Wei]、刘宏程 [Liu Hongcheng]、高晓宽 [Gao Xiaokuan]、罗双泉 [Luo Shuangquan],《基于DeepSeek大模型的军事指挥能力提升路径研究:技术优势与战场应用展望》[Research on the Pathways to Enhance Military Command Capability Based on the DeepSeek Large Model: Technical Advantages and Battlefield Application Prospects],国防科技大学信息通信学院 [College of Information and Communication, National University of Defense Technology],第十三届中国指挥控制大会 [The 13th China Command and Control Conference], (2025).

[2] 麻玥瑄 [Ma Yuexuan]、齐家悦 [Qi Jiayue]、朱威禹 [Zhu Weiyu],《大模型赋能无人机博弈对抗研究》[Large Models Empower Research on UAV Game Confrontation],《空天技术》[Aerospace Technology], (2025年第3期): 79–96.

[3] 王本昆 [Wang Benkun]、房明星 [Fang Mingxing]、丁锋 [Ding Feng]、孟令杰 [Meng Lingjie],《DeepSeek对电磁态势感知未来发展的影响》[The Impact of DeepSeek on the Future Development of Electromagnetic Situation Awareness],国防科技大学电子对抗学院 [College of Electronic Countermeasures, National University of Defense Technology],第十三届中国指挥控制大会 [The 13th China Command and Control Conference], (2025).

[4] 邹通 [Zou Tong]、丁学良 [Ding Xueliang]、戴瀚苏 [Dai Hansu]、李超勇 [Li Chaoyong],《基于大语言模型的集群作战决策研究》[Research on Swarm Operations Decision-Making Based on Large Language Models],《南京航空航天大学学报》[Journal of Nanjing University of Aeronautics & Astronautics], (2025年六月) [June 2025].

[5] 王鹏飞 [Wang Pengfei]、刘红琴 [Liu Hongqin]、陈向春 [Chen Xiangchun],《具身智能驱动下的无人作战系统展望》 [Prospects for Unmanned Combat Systems Driven by Embodied Intelligence],陆军炮兵防空兵学院 [Army Artillery and Air Defense Academy],《航空兵器》 [Aero Weaponry],第 32 卷 (2025 年 6 月) [Vol. 32, June 2025]; 麻玥瑄 [Ma Yuxuan]、齐家悦 [Qi Jiayue]、朱威禹 [Zhu Weiyu],《大模型赋能无人机博弈对抗研究》 [Large Models Empower Research on UAV Game Confrontation],《空天技术》 [Aerospace Technology],第 3 期 (2025 年 6 月) [No. 3, June 2025].

[6] 李为 [Li Wei]、刘宏程 [Liu Hongcheng]、高晓宽 [Gao Xiaokuan]、罗双泉 [Luo Shuangquan],《基于DeepSeek大模型的军事指挥能力提升路径研究:技术优势与战场应用展望》[Research on the Pathways to Enhance Military Command Capability Based on the DeepSeek Large Model: Technical Advantages and Battlefield Application Prospects],国防科技大学信息通信学院 [College of Information and Communication, National University of Defense Technology],第十三届中国指挥控制大会 [The 13th China Command and Control Conference], (2025).

[7] 李荣泉 [Li Rongquan], 《人工智能在公安视频监控赋能市域社会治理中的作用探析——以DeepSeek为例》 [To Analyze the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Enabling Urban Social Governance through Public Security Video Surveillance], 公安研究 [Policing Study], 2025年第7期 (No.7 2025).

[8] 刘畅 [Liu Chang] 、何伏刚 [He Fugang], 《大模型赋能警察现场执法的应用研究》[On the Application of Large Models Empowering Police On-Site Law Enforcement], 政法学刊 [Journal of Political Science and Law], 2025年第42卷第3期 (Vol. 42, No. 3, 2025).

[9] Pei, Minxin. The Sentinel State. Harvard University Press, 2024.

[10] 李红莲 [Li Honglian], 《DeepSeek给安防行业带来的机遇与变革》[Opportunities and Transformations Brought by DeepSeek to the Security Industry], 中国安防 [China Security & Protection], 2025年第5期 (No.5 2025).

[11] 付琳 [Fu Ling] 、程有序 [Cheng Youxu], 《DeepSeek 赋能新质公安战斗力的理论证成》[A Study on Theoretical Evidencing New Quality Policing Combat Capacity Empowered by DeepSeek], 广州市公安管理干部学院学报 [Journal of Guangzhou Police College], 2025年第1期 (No.1, 2025).