Hainan Revises Fishing Regulations in South China Sea: New Language, Old Ambiguities

Publication: China Brief Volume: 14 Issue: 2

By:

On November 29 of last year, Hainan’s legislature approved revised measures (banfa) for implementing the PRC Fisheries Law. Unlike earlier provincial fisheries regulations, the new measures single out “foreigners and foreign fishing vessels” as requiring special permission to operate within Hainan’s jurisdiction, effective January 1 of this year (Hainan Daily, December 7, 2013). Following controversy over China’s establishment of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in the East China Sea (ECS) (see China Brief, November 27, 2013) and amid a broader pattern of Chinese “assertiveness” in prosecuting their disputed claims to islands and maritime zones in the ECS and South China Sea (SCS), this announcement elicited critical comments from several foreign governments. Such concern is not warranted from the regulations alone.

Analysis of the text of the new banfa in comparison to previous iterations of the provincial rules and the national fisheries law it implements reveals that these measures do not expand China’s claims to maritime jurisdiction, nor do they impose new restrictions on foreign fishing vessels. They may, however, signal an intention to more fully enforce existing law in areas claimed as Chinese Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs). In addition, by failing to clarify the extent of waters under Hainan’s administration—and, in fact, being less precise about restricted zones in the Paracels (xisha) and Macclesfield Bank (zhongsha)—the revised measures carry on a policy of deliberate ambiguity about China’s jurisdictional claims in the SCS.

A War of Words

The new banfa became public when Xinhua announced the new measures on December 1, 2013, and called specific attention to an article requiring State Council permission for foreigners and foreign fishing vessels to engage in fishing activities in Hainan’s area of jurisdiction, covering two million square kilometers (Xinhua, December 1, 2013). The article went on to warn of confiscations, fines, and criminal liability for violators. The regulations did not provoke international reaction until after the banfa went into effect in the new year. On January 9, a U.S. State Department spokeswoman issued a strongly worded criticism of the new law as a “provocative and potentially dangerous act” (US State Department Daily Press Briefing, January 9). The following day, the Vietnamese foreign ministry declared that the Chinese act, and related infringements on Vietnamese fishing in disputed zones, were “illegal, null and void, and represent serious infringements on Vietnam’s sovereignty” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Vietnam, January 10). A Philippine foreign ministry statement that day also expressed “grave concern” and called on China to “immediately clarify” the new law; the Philippine foreign minister pledged to raise the issue in ASEAN ministerial meetings, which began on January 15 (Department of Foreign Affairs of the Philippines, January 10; Philippine Star, January 17). Related commentary in the international press strikes similar notes, but little attention is devoted to the content of the new Hainan regulations, nor have any reports identified changes to China’s enforcement practice. The analysis below addresses both issues.

Analysis of Banfa Text

The measures at issue are the second revision (xiugai) of the original 1993 provincial banfa, first revised in 2008. [1] Each iteration represents an attempt to bring provincial practice into line with national legislation, specifically the 2004 PRC Fisheries Law. [2] As regulation rather than law, “legally, it cannot regulate more than the fisheries law prescribes,” according to Professor Zhang Xinjun of Tsinghua University Law School (Email conversation with author, January 15, 2013). The principal regulation at issue is Article 35 of the new banfa, which stipulates that: “foreigners and foreign fishing vessels entering the waters under the jurisdiction of this province to engage in fisheries production or fisheries resource surveys must obtain permission from the relevant department under the State Council …[such individuals and vessels] must abide by national laws and regulations governing fisheries, environmental protection, entry and exit administration and related regulations of the province.” Comparison with previous Hainan regulations and the national legislation they implement demonstrates that this restriction is not new. Certain omissions and rewordings, however, are reason for close attention to Hainan’s enforcement of the new measures.

The language used in Article 35 is almost identical to that used in Article 8 of the 2004 PRC Fisheries Law, the legislation that the banfa is designed to implement. Neither the 1993 nor the 2008 versions of these measures used this exact language, though they place comparable restrictions on foreign vessels. The new article is much more specific about foreigners and foreign vessels (waiguoren, waiguo yuchuan) than prior regulations, which in article 21(3) impose a similar requirements on vessels not originating from provincial ports (waishen, qu huozhe jingwai). The new article differs primarily in singling out foreign individuals as well as vessels in a separate article, though in this respect it mimics the national legislation.

Several changes to the banfa are still notable. First, it does not mention an annual moratorium on fishing in protected areas around the Paracel Islands and Macclesfield Bank, as the previous regulations did in Article 31. Second, it is less precise about the “relevant organs under the State Council” who could, in principle, authorize foreign fishing activity in areas under Hainan’s jurisdiction; both prior measures indicate the competent office (fisheries and ports) under the Ministry of Agriculture (also Article 31). Third, Article 39 in both previous banfa specify penalties for violating provincial fisheries regulations, including confiscation of catches, fishing gear, and illegal income, as well as fines and possible prosecution in accord with Chinese criminal law; similar provisions are found in Article 46 of the national fisheries law. Article 9 of the new law gives fisheries officials authority to inspect vessels, their equipment, and cargo, but makes no mention of confiscation. Only interference with fisheries law enforcement is indicated as a cause for initiating criminal procedures. The Xinhua announcement cites penalties (seizure, fines, criminal prosecution, etc.) drawn from the national legislation, which requires local implementation measures as stipulated in previous versions of the banfa. Their omission is another unexplained ambiguity in the new document, and will need to be judged according to subsequent enforcement practice.

These relatively minor differences do not warrant expectations of drastically revised fisheries law enforcement. The thrust of the measures is to better regulate the vast but still undefined maritime zone under Hainan’s jurisdiction on issues ranging from the size of allowable catch to the types of outboard motors permitted in protected areas. Depleted fish stocks, environmental degradation, marine pollution, rampant overfishing, and national plans to develop deep-water fisheries production are all factors that plausibly justify further reform and rationalization of Hainan’s fisheries law enforcement. The technical and precise language intended to guide provincial authorities in implementing national policy does not, however, provide any greater clarity on where and to what extent these regulations are to be enacted.

Hainan’s Maritime Jurisdiction: Unclear Boundaries

However unimportant the new regulations may be, Chinese responses to the wave of criticism concerning the Hainan regulations do not address the crucial question of where those rules (or any other domestic maritime law enforcement) are to be effective. The Chinese foreign ministry stresses the continuity of its fisheries law enforcement with respect to foreign vessels, and accused critics of “ulterior motives” in lodging complaints against the new measures (Chinese Foreign Ministry Press Briefing, January 10). The bulk of PRC media commentary evinces the same attitude (First Financial Online (Yicai Wang), January 14; China News Online, January 14; Xinhua, January 10). Despite the validity of the basic claim that there is no substantive change to China’s law regarding foreign activity in waters under its claimed jurisdiction, there remains a glaring omission: China has still not clarified the geographical scope of those waters and their status under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

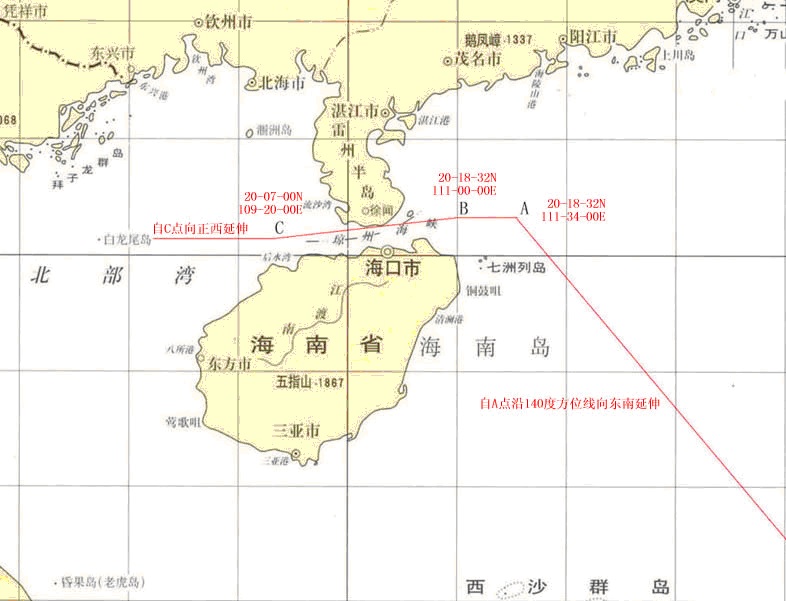

The Xinhua press release announcing the new banfa asserts that Hainan is responsible for some 2 million square kilometers of relevant maritime area (xiangguan haiyu). The only official document citing this figure is the relatively obscure Twelfth Five-Year Plan of the Hainan Maritime Safety Administration (MSA) (Hainan Maritime Safety Administration, July 7, 2012). The Hainan MSA document claims that the province administers roughly two thirds of China’s overall maritime space (woguo haiyu), sets basepoints for the northern tier of waters under Hainan’s administration, and extends a line south-east at 140 degrees from the Qiongzhou Straight as the north-eastern boundary of that zone (see Figure 1 below). By inference, this line encloses the Macclesfield Bank, and then intersects the now-infamous U-shaped, or “nine-dashed,” line, thus including the disputed Spratly and Paracel Islands as well as areas claimed as the EEZ of Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei and the Philippines. In short, the new measures make negligible revisions to China’s restrictions on foreign activities while missing another opportunity to remove ambiguity about the precise extent of the PRC claim to maritime jurisdiction.

The Proof is in the Practice

Nothing in the text of the banfa implies any necessary change to China’s fisheries law enforcement, but comments from knowledgeable Chinese commentators hint at possible reasons for the new measures and likely implications for how and where the regulations will be enforced in disputed waters. In general, the expectation is that the regulations signal ramped-up enforcement moving forward. Shen Shishun, director of the department of Asia-Pacific security and co-operation at the China Institute of International Studies, argues that “our navy and law enforcement forces have not patrolled the disputed areas often enough. Now, given the strengthening of their capabilities, they will step up surveillance … That’s why we now require foreign fishing vessels to get permission” (South China Morning Post, January 10). Such comments validate foreign concerns that these measures represent one more in what appears to be a series of steps to consolidate Chinese effective control in disputed zones. The emphasis on requirements and punishment for foreign vessels in the original Xinhua announcement reinforces this interpretation. Still, enforcement will bear close monitoring moving forward to judge whether the regulations will practically affect what has been an irregular pattern of arrests of foreign fishermen and confiscations of foreign fishing catch and vessels. [3]

The measures may also mean only more targeted law enforcement in critical areas close to disputed territory. Wu Shicun, a delegate to the Hainan National People’s Congress and also President of the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, suggested that the new measures are intended to sharpen enforcement around the Paracels. “The goal is to make them not dare to come back…If you violate the rules, you will pay a high price” (Wall Street Journal, January 10). He added that enforcement activity would be focused on China’s territorial seas, which which extend only 12 nautical miles from coastal baselines. China has not officially stated which features in the SCS are entitled to the full complement of maritime zones (i.e., EEZ and continental shelf), but in drawing straight baselines around the Paracels in 1996, they controversially elected to treat the area as though it were an archipelago and therefore accessible only to foreign vessels engaged in "innocent passage" and no other navigational or operational activity. The omission of the protected area around the Paracels in the new measures makes this prediction somewhat confusing, but the trend towards enhanced effective control of this area in particular is established and may be expected to continue.

Another possibility is that the banfa will further complicate the already difficult balance of responsibilities shared by the several state and provincial agencies responsible for administering China’s maritime periphery, maritime law enforcement entities. These are: the State Oceanic Adminstration, under the Land and Resources Ministry; the China Coast Guard, under the Public Security Ministry; the Transport Ministry’s MSA; Fisheries Law Enforcement Command (FLEC) under the Ministry of Agriculture; and the General Administration of Customs (GAC). According to Lin Yun, director of legal affairs for the Hainan Department of Ocean and Fisheries, the recent reshuffle of China’s civilian maritime bureaucracy is not yet complete, meaning Fisheries Law Enforcement Command and China Marine Surveillance vessels would continue do work ultimately intended for a unified coast guard under the State Oceanic Administration (South China Morning Post, January 11). Such an interpretation is consistent with last year’s similarly-scrutinized revision to Hainan’s Regulations for the Management of Coastal Border Security and Public Order, the 2012 upgrade of Sansha City’s administrative status from county- to prefecture-level, and broader national priorities to enhance the development of China’s maritime economy. [4]

Lin also noted that the ambiguity over the scope of the waters under Hainan’s administration cannot be determined by provincial regulations—only an act of national legislation could delimit the area in question. China’s 1998 Law on the EEZ and Continental Shelf announces China’s intention to claim the maximal entitlement (200nm) from its coastal baselines, but none have been fixed in the Spratlys to date, and the U-shaped line lacks precise coordinates. [5] If the new banfa leads to heightened activity from any or all of China’s maritime law enforcement agencies, it may well clarify the content of the Chinese claim to jurisdiction by providing further evidence of what activities it will restrict in which areas. This incremental, “creeping jurisdiction” may not establish the exact parameters of the Chinese claim but will place growing obstacles in front of claimants seeking to assert their sovereign rights in zones increasingly regulated by Chinese domestic agencies.

Notes

- 1993 text available at < https://www.law-lib.com/law/law_view.asp?id=23536 >; 2008 revision at < https://www.hainan.gov.cn/data/law/2008/08/1157/ >.

- This law was promulgated in 1986, and amended in 2000 and 2004. Full text at: < https://www.gov.cn/flfg/2005-07/18/content_15802.htm >

- M. Taylor Fravel, “China’s Strategy in the South China Sea,” Contemporary Southeast Asia, 33(3) (2011), p. 305.

- See M. Taylor Fravel, “Hainan’s New Maritime Regulations: An Update,” The Diplomat, January 3,” and Dennis Blasko and M. Taylor Fravel, “Much Ado About The Sansha Garrison,” The Diplomat, August 23, 2012.

- Text of law available in English at < https://www.un.org/depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/chn_1998_eez_act.pdf >.

This article was revised on January 23, 2014, to provide additional information.