Mongolia Nurtures Relations with North Korea As It Hopes for Official Future Role in Six-Party Talks

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 226

By:

Mongolia grabbed the headlines on November 15–16 by the announcement that Japan and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) were engaging in direct senior-level talks in the Mongolian capital of Ulaanbaatar about the issue of North Korea’s abduction of Japanese nationals. The presence of high-ranking diplomats from both sides, led by Shinsuke Sugiyama, director-general of the Japanese Foreign Ministry’s Asian and Oceanic Pacific Bureau, and Song Il-ho, ambassador in charge of negotiations with Japan at the DPRK Ministry of Foreign Affairs, indicated that Mongolia is an interested intermediary with a unique ability to inspire confidence. Mongolian officials emphasized that arranging this recent meeting reflected Ulaanbaatar’s “contribution to satisfy regional stability in Northeast Asia,” and how it could play a role in deepening understanding and normalizing DPRK-Japan relations (Mongol Messenger, November 16). Mongolian President Tsakhia Elbegdorj’s government staged the negotiations at the official state compound in Ikh Tenger apparently at the behest of the North Koreans. The president explained that: “…Japan, North Korea and other countries can come to discuss this issue on Mongolian soil. We would like to contribute to that. That is our only purpose” (www.newsmate.kr, November 16).

Right after the close of the discussions, the two delegation leaders met separately with Mongolian Foreign Affairs Minister Luvsanvandan Bold to thank the hosts for facilitating the dialogue. Results were positive enough for the parties to announce a second round, which was to take place in Beijing on December 6–7. Reportedly Pyongyang expressed openness to Tokyo’s proposal to set up a joint investigatory commission to determine the actual fate of Japanese abductees. (www.japantimes.co.jp, November 23). However, Japan postponed the next round after North Korea announced plans to launch a rocket later in December (Kyodo News Agency, December 2). Japanese officials and Song previously had warned that negotiations would be difficult and not lead to immediate breakthroughs (www.infomongolia.com, November 16; www.arirang.co.kr, November 19).

The last such high-level meeting had occurred in Mongolia in September 2007 when a Working Group responsible for normalizing DPRK-Japanese relations had met under the Six-Party Talks mechanism. But, unnoticed in the Western press, were secret Japanese-DPRK meetings in Mongolia on March 17–18, 2012, when Song met with Sadaki Manabe, professor at Takushoku University and director of an organization assisting citizens abducted by North Korea. Manabe was a stand-in for Japanese MP Nakai Hiroshi, who had been in charge of abductees for the Japanese government until 2009. After those March discussions, Lundeg Purevsuren, foreign policy advisor to the Mongolian president, commented on the need for secrecy by noting that Japanese and North Korean relations were complicated by misunderstandings including the abduction issue. Purevsuren indicated that the Mongolians did not participate at all in the meetings due to the fact that Mongolia was not currently involved in the Six-Party Korean Peninsula talks. But he stressed that hosting this unofficial meeting has bolstered Mongolia’s foreign policy reach and increased Ulaanbaatar’s likelihood of taking “an active part in talks being held in Northeast Asia” (Odriin Sonin Daily, March 21; Mongol Messenger, March 23). The success of the two rounds of 2012 meetings and Purevsuren’s comments indicate Mongolia would be interested in becoming more active in the Korean Peninsula talks and that China and the United States may not be able to continue to deny Mongolia a seat at the table (Alicia Campi, “Mongolia Receives Conflicting Advice on Asian Policies from U.S. at 1st Bilateral Conference,” Pac NET, May 2005).

Although Mongolian officials promote their concern for human rights and their commitment to democracy and the free market, they also are very committed to having a strong relationship with North Korea. Mongolia in 1946 was the second country after the Soviet Union to recognize the DPRK. On the death of Kim Jong-Il in 2011, the Mongolian president and prime minister were quick to send letters of condolence, and the Mongolian official government news agency Montsame named Kim’s death as one of the top ten events of that year (Mongol Messenger, December 23, 2011). Such gestures overtly appeal to the North Korean sensibility.

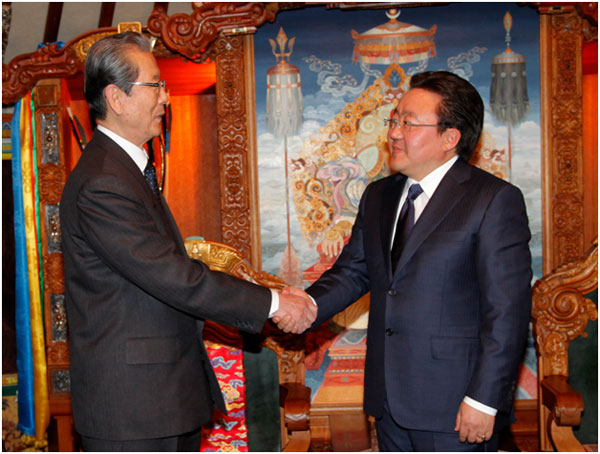

On November 18–22, a delegation led by Choe Tae Bok, Chairman of the DPRK supreme assembly, paid an official visit to Ulaanbaatar. The domestic press prominently covered the North Koreans’ meetings with Mongolian Deputy Parliament Speaker and head of the Mongolia-DPRK parliamentary group, Sangajav Bayartsogt, Parliament Speaker Zandaakhuu Enkhbold, and other parliamentary leaders, as well as with President Elbegdorj. Choe declared, “Our two countries have friendly relations from ancient times. We are satisfied with developing cooperation between the two countries. A DPRK-Japan intergovernmental talk recently held in Ulaanbaatar is proof of how these three nations have friendly relations” (Mongol Messenger, November 23).

Indeed, the two countries have sought more intensive forms of economic cooperation. As China attempts to meet its demand for coal, Mongolia and North Korea are viewed as nearby producers whose resources can be developed relatively cheaply by Chinese FDI (Global Coal Risk Assessment: Data Analysis and Market Research, World Resources Institute, November 2012). At present, both countries’ raw coal production is overwhelmingly destined for China, but now it is a priority for the Mongolian government to diversify its customers by improving rail and port connections through Russia and the DPRK. Thus, Parliamentary Speaker Enkhbold told the visiting Koreans that Mongolia wants to export products to the North, exchange labor forces, collaborate in the IT sector, and continue an agreement on renting facilities at a DPRK seaport. Choe responded: “The DPRK proposes to cooperate in economic regional development, grant access to the sea and in the coal and mining sectors” (Mongol Messenger, November 23).

The delegation also was received by President Elbegdorj who proposed that bilateral cooperation should focus on four points: 1) maintenance of high-level visits with an invitation for DPRK Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un to come to Mongolia; 2) co-exploitation of natural resources, co-establishment of the necessary infrastructure, and co-production of high-end products from raw materials; 3) consideration of providing food aid to North Korea; and 4) seeking to resolve the Korean Peninsula issue in a peaceful way, and thus Mongolia’s readiness to host more Six-Party Talks (www.infomongolia, November 19; Mongol Messenger, November 23). Ulaanbaatar’s closer relations with Pyongyang thus represent not just an economic opportunity, but also a means for Mongolia to bolster its foreign policy reach within Northeast Asia.