Tajik-Iranian Ties Flourish

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 8 Issue: 66

By:

Iran has steadily expanded its economic position in Tajikistan since the start of 2011. In February, a private Iranian company signed an agreement with the Tajik Ministry of Energy and Industry (MEI), pledging to build a large cement plant in Tajikistan’s southern Khatlon province. When completed, the coal-driven plant is expected to produce two million metric tons of cement annually, using local limestone reserves. The company will also build a coal power plant to supply energy to the cement producing facility. According to the MEI, Iranian investment in the project will total $500 million (www.avesta.tj, February 9, 18).

Iran’s hitherto largest investment project in the country aims to help Tajikistan meet its steadily growing demand for cement. Boosted by large-scale energy and infrastructure projects, the demand is presently estimated at 1 million to 1.5 million tons per year and continues to increase. With domestic production standing at only 290,000 tons in 2010, Dushanbe has heavily relied on cement imports from Pakistan and Iran to meet its needs (www.cacianalyst.org, February 2, 2011). The Iranian-built plant is expected to provide Tajikistan with surplus cement output that can be used in new infrastructure projects or exported.

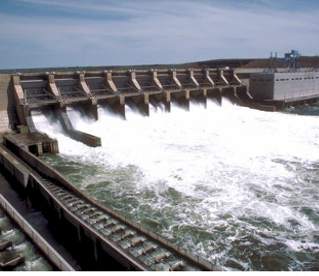

Tehran’s embassy in Dushanbe also announced in February that Iran will continue investing in the Tajik energy sector. Iran has already invested about $180 million in the construction of the Sangtuda-2 hydropower plant (HPP) on the Vakhsh River in central Tajikistan. The final cost of the plant will increase markedly because, following the Tashkent-imposed ban on the transportation of materials for Tajik energy projects through the Uzbek railway, Tehran has to deliver critical supplies for the plant by air (www.ozodi.tj, March 10, 2011). The Sangtuda-2 HPP which is expected to begin operating this year will produce 220 megawatts of electricity annually, helping Dushanbe tackle its energy deficits.

The plant appears to be the first among several hydropower projects that Tehran intends to pursue in Tajikistan. After commissioning the facility, Iran will build the 170-megawatt Ayni HPP on the Zarafshon River in northern Tajikistan. Moreover, according to the Iranian embassy in Dushanbe, Tehran is currently reviewing the Tajik government’s proposal to build two larger hydropower plants on the Obi Khingob River in Tajikistan’s Rasht Valley. If completed, these plants will each produce an estimated 350 megawatts of electricity annually (www.news.tj, February 9).

While it remains unclear at the moment whether Tehran will have the resources and will be willing to build the three additional power plants in Tajikistan, these projects might help Iran become a major player in the country that has been its principal ally in Central Asia. Iran is among Tajikistan’s major economic partners. Trade between the two countries stood at $400 million in 2010, up from $250 million in the previous year. According to the Tajik investment committee, Tehran was the largest investor in the Tajik economy in 2010, contributing $65.5 million in foreign direct investment (FDI) (www.news.tj, February 9, 2011).

In addition to increasing Iran’s economic clout in Tajikistan, the energy projects will give Tehran additional political leverage in the country. Dushanbe has long viewed hydropower projects as the backbone for the country’s development. The Tajik government views Tehran’s intention to build the power plants on the Zarafshon and Obi Khingob rivers with particular appreciation because Uzbekistan’s opposition to the plant had previously forced Chinese and Russian companies to abandon these projects (www.dw-world.de, February 28).

During his visit to Iran in March, Tajik President Emomali Rahmon also invited Iranian businesses to set up joint ventures with Tajik companies in the country’s free economic zones. According to the Tajik president, the two countries are discussing the creation of such ventures in Tajikistan that will process fruit and vegetables, and produce energy saving light bulbs, solar panels and power transformers (www.regnum.ru, March 27).

Iran has also steadily increased its cooperation with Tajikistan’s state geological agency, Geologiyai Tojik, which is responsible for the exploration and mining of minerals in the country. Iranian experts have been actively engaged in the exploration of gas and limestone reserves in Tajikistan. This cooperation has fueled speculation in the Russian media that Tehran sought to map out Tajikistan’s uranium deposits as part of its global search for uranium for the country’s allegedly peaceful nuclear program (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, January 11, February 11).

There is little reliable data about economically viable uranium reserves in Tajikistan, partly because this information has been classified since the Soviet period. President Rahmon claimed in 2008 that Tajikistan was home to 14 percent of the world’s uranium reserves. Subsequently, amendments were introduced to the national legislation, allowing foreign companies to mine uranium in Tajikistan (www.cacianalyst.com, September 16, 2009). It is currently impossible to verify the validity of claims by the Russian media about Tehran’s interest in Tajik uranium.

Flourishing economic ties with Dushanbe look certain to expand Iran’s political and strategic position in Tajikistan and the Central Asian region at a time when Tehran faces increasing international pressure over its nuclear program.