North Caucasus’ Ethnic Russian Population Shrinks as Indigenous Populations Grow

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 6 Issue: 210

By:

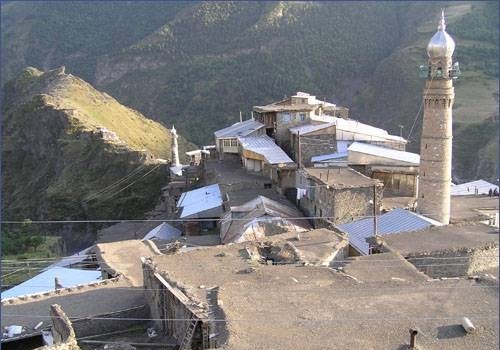

On November 3, Dagestani President Mukhu Aliev held a special meeting of the commission dedicated to the problems of ethnic Russians living in the republic. Despite the optimistic tone of the officials, it appears that ethnic Russians are still leaving Dagestan, although in fewer numbers than immediately after the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991. According to President Aliev, Russians comprised 20 percent of Dagestan’s population, and were the second largest ethnic group in this ethnically diverse republic in 1959. However, by 1989, the ethnic Russian population had decreased to 9 percent of the republic’s total and in the following years to less than 5 percent. Today, ethnic Russians rank sixth among numerous ethnicities of Dagestan; the Avars, Dargins, Kumyks, Lezgins and Laks each number more than the Russians. In the period between two Russian censuses in 1989 and 2002, the Russian population in Dagestan declined –according to the official figures, by 27 percent, down to 120,000 (www.riadagestan.ru, November 3).

Dagestan is the largest of the seven North Caucasian republics, with an estimated population of 2.7 million as of January 1, 2009. It has also the largest natural growth in absolute numbers: in 2008, its population added over 30,000 people. The population of the Russian Federation declined by over 300,000 in the same year (Russia’s state statistical service, www.gks.ru).

The same trend of a declining ethnic Russian population can be seen in other republics of North Caucasus. Chechnya saw the most dramatic reduction of the Russian population due to two bloody wars and the ensuing period of lawlessness and low grade warfare. It is estimated that the Russian population of Chechnya dropped by 250,000 in the period between 1989 and 2002. According to the official numbers, the Russian population across all the republics of the North Caucasus declined by 364,000 people during the same period. However, the real numbers are likely to have been higher: experts estimate that the Russian population dropped by 415,000-420,000 or 31 percent of the ethnic Russian population of the North Caucasian republics, which brought the number of Russians in the region from 1.36 million in 1989 down to 940,000 to 945,000 in 2002. By way of comparison, in the previous statistical period 1979-1989, the ethnic Russian population in the North Caucasus decreased only by 53,000 or 4 percent (www.valerytishkov.ru).

The discrepancy between the official numbers and the expert estimates is explained by counting some Slavic groups (Belarusians) as ethnic Russians in the 2002 census data, as well as counting the newly deployed Russian troops as part of the permanent local population. From 1989-2002, the percentage of the ethnic Russian population in the overall population of North Caucasian republics decreased from 26 percent down to 12-15 percent, while the indigenous populations grew from 66 percent up to 80 percent –or, in absolute numbers, from 3.5 million to 5.3 million (www.valerytishkov.ru).

The issue of the declining Russian population in the republics of North Caucasus has been politically sensitive for the Kremlin and the general Russian public, as the retreat of ethnic Russians from this region has been equated with losing control over it. So the state statistical service has tried to improve the picture by downplaying the decrease of the ethnic Russian population in the region. With the general population of the North Caucasian republics nearing 7 million and the constant decline in the ethnic Russian population, this may be an understandable fear. However, it can also be explained by the historical legacy of the Russian empire, which increased its territory in concentric circles and heavily relied on ethnic Russian settlers’ numerical prevalence over the local population and its eventual assimilation.

War and personal insecurity have been cited as the main causes of the ethnic Russians’ outflow from the Northern Caucasus. Indeed, the two largest shedders of Russian population have been Chechnya and Ingushetia, which currently have almost no Russians living in them except for members of the Russian military. The region’s rapid economic decline is thought to be another important factor that has fueled the outflow of ethnic Russians. This also looks like a viable explanation, given that not only ethnic Russians, but also indigenous peoples of the North Caucasus leave the region in search of better economic opportunities. Currently, the majority of the migrants from the North Caucasus to inner Russian regions and abroad are members of non-Russian ethnic groups.

With the exodus of the Russian population from the North Caucasus, the Russian language also appears to be in retreat –to the extent that some republics, like Dagestan, are creating special government programs to support the Russian language. A Russian language council has been created under the president of Dagestan and a special program to support the Russian language has been adopted, that strives, according to an official website, “to support, develop and spread the Russian language in Dagestan” (www.riadagestan.ru, November 3). While the local elites habitually try to appease Moscow by creating similar “pro-Russian” programs, it is still symptomatic that Russian, the lingua franca of the Russian Federation, would need any support at all from a provincial government.

One of the most fundamental causes of the depletion of the North Caucasus’ Russian population is often overlooked. As the indigenous peoples’ self-consciousness has grown and their educational level practically equaled the levels in the rest of Russia, no social niche has been left for ethnic Russians to fill. This effectively means that regardless of developments in the near future, whether the security or economic situation improves in the North Caucasus or not, the trend of the outflow of ethnic Russians will hardly be reversed. The only way of reversing this trend, which is so negative for Moscow, would be to effectively pacify the region and make huge investments to provide incentives for ethnic Russians to resettle in the region en masse. Even if Moscow succeeded in calming the Caucasus, it would have so many other economic priorities to address that the North Caucasus would hardly be among them