BRIEFS

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 1

By:

SOUTH SUDAN’S TRIBAL “WHITE ARMY” – PART ONE: CATTLE RAIDS AND TRIBAL RIVALRIES

Andrew McGregor

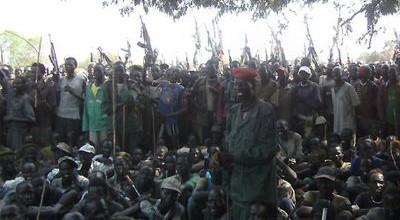

One of the most important developments in the ongoing political and tribal violence in South Sudan is the apparent re-emergence of a largely Nuer militia known as “the White Army.” More of an ad hoc assembly of tribal warriors than an organization, the White Army has a checkered history involving ethnic-based massacres of civilians and has played an important role in the breakdown of traditional order in South Sudan.

The current crisis in South Sudan began as a dispute between President Salva Kiir Mayardit (a member of the dominant Dinka tribe) and his vice-president, Riek Machar (a member of the Nuer, South Sudan’s second-largest tribe). With rumors flying of a failed coup-attempt by Machar, clashes began breaking out in mid-December in Juba, the South Sudan capital, between Dinka members of the presidential guard and members of the largely Nuer Tiger Division Special Forces unit. Over 1,000 people have been killed over the following weeks in the ongoing violence.

In late December, a UN surveillance aircraft reported large numbers of armed men marching on Bor, the capital of Jonglei state. Bor had been seized earlier by Nuer fighters but had been driven out by the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA – the former rebel movement now turned national army) after several days of heavy fighting. The SPLA then took up defensive positions in expectation of the arrival of 20,000 or more armed members of the White Army (Radio Miraya [Juba], December 30, 2013). The predominantly Dinka population of Bor was thrown into panic by news of the approaching White Army – the militia had joined members of Riek Machar’s SPLA-Nasir faction in a massacre of over 2,000 Dinka civilians in Bor in 1991. The destruction of the local cattle-based economy in the raid led to the deaths of thousands more from starvation in the following weeks and months. An SPLA spokesman claimed the White Army’s current march on Bor was being directed by Riek Machar (VOA, December 28).

On December 29, 2013, South Sudan’s Minister of Information said that Nuer elders in Jonglei had persuaded the bulk of the White Army to disband and return home (AP, December 29, 2013). However, on the same day, a spokesman for President Kiir denied these reports, saying the White Army had ignored the pleas of the Nuer elders and had clashed with government forces: “They seem to be adamant because they think that if they don’t come and fight, then the pride of their tribe has been put in great insult” (BBC, December 29, 2013). SPLA spokesman Philip Aguer said the army had used helicopter gunships to disperse the militia (al-Jazeera, December 29, 2013).

A spokesman for Riek Machar’s forces said that they “co-ordinated” with the White Army, but as the White Army is a civilian force, they did not have command over it: “We are not controlling the White Army. We are controlling our forces, Division 8, the SPLA that’s whom we know [the SPLA’s Jonglei-based Division 8 has supplied most of the military defectors to Machar’s cause]” (Radio Tamazuj, December 29, 2013).

Due to its decentralized structure and ad hoc formation, there are few documents describing the White Army’s ideology or political approach and those that do exist are often contradictory. One such statement was issued in May 2006 by the largely Nuer South Sudan Defense Force (SSDF) and its political wing, the South Sudan United Democratic Alliance (SSUDA). [1] Apparently acting as a spokesman for the militia, the statement was written by SSDF member Professor David de Chand (an American-educated Nuer). De Chand accused the SPLA’s political wing of using “Nuer oil revenue to kill Nuer” and accused its leadership of harboring a “hidden agenda of superimposing the Dinka power elite’s hegemonic tendencies.” According to the statement:

However, there are reasons to question the legitimacy of this document as an authentic statement of White Army beliefs. The pro-Khartoum SSDF had at times acted as a sponsor of the White Army, but though the SSDF obtained some influence over its activities, the White Army never came under its direct command. De Chand was better known at the time as a Khartoum-based politician firmly in the camp of the ruling Omar al-Bashir regime than a Nuer militia leader. Even as the statement was issued, most of the SSDF, including its leader Paulino Matip Nhial, was being integrated into the SPLA in accordance with the 2006 Juba Declaration that called for former pro-Khartoum militias to be integrated into a broader SPLA that would represent all of South Sudan’s tribal groups. De Chand remained with a rump SSDF faction that continued to oppose Juba. This statement and its accusations of planned genocide by the Dinkas must be viewed in the light of Khartoum’s campaign to spread political dissension in advance of the 2011 referendum on South Sudanese independence.

A more legitimate media statement released in 2012 under the name of the “Nuer and Dinka White Army” asked for Dinka cooperation against cattle raiders of the Murle tribe and emphasized the membership of the Twic Dinka (a Dinka clan traditionally allied with its Nuer neighbors that has also suffered from Murle cattle raids) in the White Army, along with elements of the Lou, Jikany and Gawaar Nuer. The group was meeting at the time with Nuer groups living in south-west Ethiopia that had also been subject to Murle cattle raids. [2] In December 2011, a Nuer Youth/White Army statement claimed the movement had decided the only way to guarantee the security of Nuer cattle was to “wipe out the entire Murle tribe on the face of the earth” (Upper Nile Times, December 26, 2011).

The militia has support and fundraisers amongst the Nuer diaspora community in the United States, which is centered in Seattle. The White Army’s U.S. fundraising wing is called the Nuer Youth in North America, headed by a Seattle-based Nuer refugee, Gai Bol Thong. The Nuer Youth runs a fundraising network extending to other cities in the United States and Canada hosting Nuer communities. Gai Bol came under criticism in early 2012 when he told a reporter: “We mean what we say. We kill everybody. We are tired of [the Murle]” (New York Times, January 12, 2012). The fundraiser toned down his remarks the following day, saying that “killing everybody” did not include children (Seattle Weekly, January 13, 2012).

Notes

1. David de Chand, “White Army declares protracted confrontation against SPLM/A,” South Sudan United Democratic Alliance/ South Sudan Defense Force Press Release, May 23, 2006, https://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article15813.

2. “Nuer and Dinka White Army to Launch ‘Operation Savannah Storm’ against Murle Armed Youth,” Leadership of the Nuer and Dinka White Army Media Release, Uror County, Jonglei State, South Sudan, February 4, 2012, https://www.southsudannewsagency.com/news/press-releases/nuer-and-dinka-white-army-to-launch-operation-savannah-storm-against-murle-armed-youth.

COMMANDER OF IRAQ’S JAYSH AL-MUKHTAR MILITANTS ARRESTED

Andrew McGregor

Following attacks on a U.S.-supported Iranian dissident group based in Iraq and a Saudi border post as well as public threats to hit targets in Kuwait, Jaysh al-Mukhtar (Army of the Chosen) leader Wathiq al-Battat was arrested at a Baghdad checkpoint on January 2.

The stated intention of Jaysh al-Mukhtar at its founding was to protect Iraq’s Shia population and aid the national government in fighting Sunni extremist groups such as al-Qaeda and the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Al-Battat told AP in February 2013 that Jaysh al-Islam was armed by Iran, though Iranian authorities have strongly denied such claims (AP, February 26, 2013). Ahmad Abu Risha, leader of the Sunni Awakening National Council in Iraq, has accused the Shiite-dominated Iraqi government of sponsoring and protecting Jaysh al-Mukhtar (al-Arabiya, February 27, 2013). Prior to forming Jaysh al-Mukhtar in February 2013, al-Battat was a senior figure in Iraq’s Hezbollah Brigades. Al-Battat claims to operate with the approval of all the senior Shia religious authorities in the holy city of Najaf and regards Iranian Ayatollah Seyed Ali Hosseini Khamenei as the leader of Jaysh al-Mukhtar (al-Hayat, February 24, 2013).

Jaysh al-Mukhtar claimed responsibility for firing 20 Katyusha rockets and several mortar rounds at the Mujahideen-e-Khalq (MeK – People’s Mujahideen Organization of Iran) compound in the former U.S. “Camp Liberty” (re-named Camp Hurriya) in Baghdad on December 26, 2013, killing three MeK members and wounding several others. Al-Battat justified the attack by saying his movement had repeatedly asked the Iraqi government to expel the MeK, “but they are still here.” The MeK saw the hand of the Maliki government behind the attack, while the United States called for the perpetrators to be found and held accountable (Reuters, December 27, 2013). The MeK is a former Marxist group best known for its terrorist attacks against the Iranian regime and an often bizarre personality cult built around its Paris-based leaders. The group enforces isolation from the outside world and bans personal relationships between its male and female members.

Once closely allied to Saddam Hussein, the MeK was a U.S.- and EU-designated terrorist group until both these bodies abandoned the designation following a well-funded lobbying campaign, which fortuitously coincided with a Western desire to pressure Iran in the confrontation over the Islamic State’s nuclear ambitions. The turnabout ignored widespread reports of the movement’s cult-like activities under the leadership of Maryam and Massoud Rajavi (the latter has not been seen in public since 2003). The U.S. Department of State revoked the terrorist designation in September 2012, allowing the group access to frozen assets, but also noted that “the Department [of State] does not overlook or forget the MEK’s past acts of terrorism, including its involvement in the killing of U.S. citizens in Iran in the 1970s and an attack on U.S. soil [against the Iranian UN Mission in New York] in 1992. The Department also has serious concerns about the MEK as an organization, particularly with regard to allegations of abuse committed against its own members.” [1] Both Iraq and Iran continue to designate the MeK as a terrorist group despite its renunciation of violence in 2001.

Al-Battat may have felt he had a free hand to act against the MeK at Camp Hurriya after 52 members of the MeK were slain in a September 1, 2013 raid by Iraqi security forces against another MeK compound at Camp Ashraf, north of Baghdad (BBC, September 1, 2013). The raid was just one of many clashes between Iraqi security forces and the MeK since 2009, including a July 29, 2009 raid that killed 11 members of the MeK and injured over 500 others at Camp Ashraf.

Al-Battat’s group had previously launched rockets and mortar rounds at the MeK compound in Camp Hurriya on February 9, 2013, killing eight and wounding nearly 100 without any serious government response, despite calls from Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki for his arrest. Shortly after the first strike on Camp Hurriya, al-Battat vowed to target the camp again, saying his movement regarded “striking and killing [MeK members] as an honor as well as a religious and moral duty” (al-Hayat, February 24, 2013).

Jaysh al-Mukhtar also claimed responsibility for a November 2013 mortar attack on an uninhabited area near a Saudi Arabian border post, which al-Battat described as a warning to the kingdom to end its involvement in Iraqi affairs (Reuters, November 21, 2013). Reflecting the strength of Shia eschatological beliefs, al-Battat has sworn to “annihilate the infidel, atheist Saudi regime” and all the regimes that support Israel and America by marching on Saudi Arabia with the Hidden Imam upon the latter’s return (Sharqiya TV, February 5, 2013). Twelver Shia Muslims believe the 12th Imam (Muhammad ibn Hasan al-Mahdi) has been in hiding in a cave underneath a Samarra mosque since the late ninth century and will return to battle the forces of evil shortly before the Day of Judgment. When it briefly appeared a U.S.-led strike on Syria was imminent in September 2013, al-Battat promised to “cut the West’s economic artery” by attacking Saudi Arabia’s oil facilities and ports in retaliation (Fars News Agency [Tehran], September 11, 2013). Al-Battat’s threats to Kuwait, however, were based on the latter’s decision to build a new port that would compete with the nearby Iraqi port of Umm Qasr (al-Siyasah [Kuwait], February 25, 2013; al-Arabiya, February 27, 2013).

Note

1. “Delisting of the Mujahedin-e Khalq,” U.S. Department of State Media Note, Office of the Spokesperson, Washington D.C., September 28, 2012, https://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2012/09/198443.htm.