Buying Silence: The Price of Internet Censorship in China

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 1

By:

Introduction

On Monday, November 12, 2018, the recently-appointed director of China’s Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission (CAC) Zhuang Rongwen (庄荣文) summoned senior executives from WeChat and Sina Weibo for a “discussion” (Central CAC, November 16, 2018). While there is no transcript of the meeting available to the public, one thing is certain: It did not go well. For months, Zhuang had been telegraphing his discontent with the state of censorship in China—and specifically, the role that social media giants had played in undermining it (New America, September 24, 2018). His official statement about the meeting, which was uploaded to the CAC’s website a few days later, accused China’s largest internet companies of “breeding chaos in the media” and “endangering social stability and the interests of the masses.” Under his watch, he vowed that the Central CAC would “strictly investigate and deal with the enterprises that lack responsibility and have serious problems” (Central CAC, November 20, 2018). Rarely do Party officials offer such scathing public admonitions.

The November 12 dressing-down heralded a fundamental change in the mechanisms of censorship in China’s New Era. Over the next two years, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) committees at lower echelons of government would stand up their own CACs to absorb the day-to-day censorship responsibilities previously headed up by Propaganda Departments. Recent studies have laid bare the bureaucratic and technical methods by which the Chinese government and Communist Party surveil and censor social media platforms, and the cost such censorship exacts on Chinese netizens.[1] What has been less clear is the literal cost—in yuan and fen—of systematically collecting, analyzing, and deleting web posts from the country’s 900 million internet users.

This article synthesizes information from more than 85 budget and expense reports and dozens of supplemental documents from Chinese government and Party offices involved in internet censorship.[2] It finds that these offices were authorized to spend more than $6.6 billion on tasks related to monitoring and guiding online public opinion (网络舆情, wangluo yuqing) in 2020, demonstrating that web censorship is one of the CCP’s top priorities.[3]

Meet the Censors

Until 2018, a myriad of Chinese government and CCP offices shared responsibility for internet censorship, resulting in a delicate and often inefficient balance of power (New America, March 26, 2018). But after the Party’s reorganization that year, two organizations absorbed the lion’s share of internet surveillance and content moderation responsibilities.[4]

- Cyberspace Affairs Commissions (CACs; 网络安全和信息化委员会, wangluo anquan he xinxihua weiyuanhui) are CCP organizations that double as government offices. The national-level Central CAC runs China’s national Online Public Opinion Information Center (网络舆情信息中心, wangluo yiqing xinxi zhongxin), which coordinates with local branches and state-owned media to monitor the valence and spread of information on the Chinese internet (S.-China Business Council, December 28, 2018). In their own words, CACs’ chief responsibilities include “organizing the ecological governance of online public opinion” and “coordinating the disposal of harmful online information” (Guangzhou Provincial CAC, 2019). To do so, they monitor posts on platforms such as WeChat and Weibo, as well as foreign social media, including Facebook and Twitter (Central CAC, April 19, 2019). CACs also employ teams of network commentators (网络评论员, wangluo pinglun yuan)—internet trolls collectively referred to as the “50 Cent Party,” (五毛党, wumao dang)—to “guide the trend of public opinion” inside and outside the country (New York Times, January 2, 2019).

- Network Security Bureaus (网络安全保卫局, wangluo anquan baowei ju) within Public Security Bureaus (PSBs;公安局, gongan ju) are government offices responsible for police work. They mete out punishments to netizens found in violation of Chinese internet law, and report to the 11th Bureau of the Ministry of Public Security. PSBs have adopted what they refer to as “slap on the shoulder” internet policing, whereby officers monitor activity on web platforms and can issue warnings to offenders by messaging them directly. In case there were any doubts, the Central CAC clarifies: “The cyber police are right by your side. The eyes of the supervisor are watching you. You will tighten a string, and you will have the necessary scruples. You will exercise restraint and rationality when you post and write messages.” Netizens are advised to consider “what should be said and what should not be said” on the internet (Central CAC, September 28, 2015).

A wide array of other organizations, including internet service providers, data analytics companies, and social media websites also contribute to internet censorship in China—to say nothing of the related work carried out by the CCP’s massive propaganda apparatus (MacroPolo, September 12, 2018; China Brief, May 15, 2020). This article focuses narrowly on spending by the Chinese government and CCP entities responsible for monitoring, removing, and amplifying web content. It therefore reflects only a portion of the resources China spends carefully crafting its online media environment.

Estimating Nationwide Spending on Internet Censorship

This study estimates nationwide censorship spending by examining 85 budget documents from a sample of CACs and PSBs in provinces, municipalities, and counties across China.[5] Specifically, it considers these organizations’ spending on two line items most closely related to censorship: “cyberspace affairs” (网信事务, wang xin shiwu) and “informatization construction” (信息化建设, xinxihua jianshe).[6]

Several limitations constrain to this approach. It is not possible to locate the budget reports of every CAC and PSB in China, and the most important organization involved in censorship—the Central CAC—does not disclose its budget. Moreover, several PSBs classify part or all of their budgets, and therefore may spend more on censorship than their publicly available “informatization construction” line items would indicate. Despite these constraints, this paper arrives at a rough estimate: In recent years, Chinese government and CCP offices engaged in internet censorship likely spent more than $6.6 billion (nominal USD) annually on related activities. Accounting for purchasing power parity, the number is likely closer to $13 billion.

Table: Estimated Value of Budget Items Related to Internet Censorship in China (2020 USD)

| Level of Governance | Avg. CAC Spending on “Cyberspace Affairs” | Avg. PSB Spending on “Informatization Construction” | Number of Administrative Units (Sealand Securities, January 26, 2016) | Estimated Total Censorship Spending in 2020 |

| Central (中央) | Unknown | $55,474,326 | 1 | $55,474,326 |

| Provincial (省/自治区) | $12,216,436 | $14,141,075 | 31 | $817,082,839 |

| Municipal (市/州) | $964,373 | $3,440,023 | 400 | $1,761,758,428 |

| County (县/区) | $276,101 | $1,053,847 | 3,000 | $3,989,845,011 |

| Estimated Nationwide Spending on Internet Censorship | $6.6 billion | |||

Statistics compiled by author.

How China’s Censors Spend Their Money

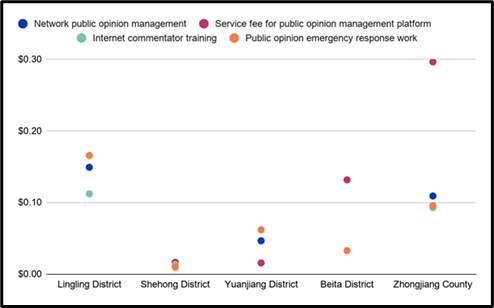

Broadly speaking, the Party’s censorship activities fall into one of two categories: first, silencing netizens that stand against its interests—including “‘democracy activists,’ ‘rights lawyers,’ and ‘dissidents’ at home and abroad” (Central United Front Work Department, September 29, 2018)—and second, generating noise to crowd out online discussions of sensitive topics. Because the names and descriptions of censorship tasks do not map perfectly across organizations, it is difficult to calculate how much money the CCP writ large may spend on specific activities, such as deleting web posts. After examining line-by-line expenditures in a few districts, however, it is evident that CACs fund similar projects and share basically the same set of priorities. These include paying subscription fees to social media sentiment analysis companies, training batches of new internet trolls, and paying the salaries of system administrators and web content moderators.[7] The following graph showcases specific line items that appear across multiple county-level CAC budget documents:

CACs’ chief responsibility is to remove content from social media platforms. In the Fengrun district of Tangshan, Hebei Province, for example, the local CAC states its goal clearly: “Delete bad information” (Fengrun District CAC, 2020). One of its performance targets last year was to report at least 600 “pieces of negative public opinion” to the municipal party committee. In Jincheng, Shanxi, the municipal CAC enumerated 25 responsibilities that variously included “public opinion response and disposal,” “online propaganda work,” “network civilization construction,” and “overseas network public opinion monitoring” (Jincheng Municipal CAC, 2019). A key goal for most CACs is to keep the rate of major online public opinion incidents (重大网络舆情发生率, zhongda wangluo yuqing fashenglü) as low as possible (Midu County Propaganda Department, 2020; Luanzhou Municipal CAC, 2020). Nearly every CAC budget document reviewed in this study mentioned “guiding,” “managing,” or “disposing of” public opinion in some fashion.

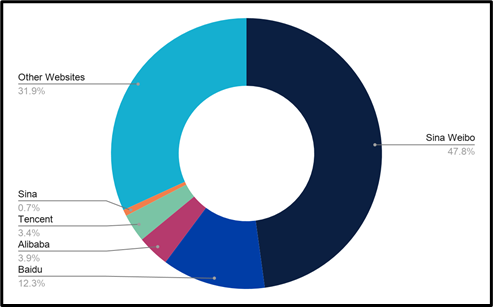

“Guiding public opinion” in a country as large as China is an onerous and expensive task. In addition to proactive censorship, CACs across the country solicit reports from Chinese netizens and collectively accepted more than 138 million reports of “illegal and bad information” in 2020.[8] Based on statistics from major cities like Beijing and Guangzhou, the vast majority of deleted content likely consists of spam, fraud, or pornography (Central CAC, September 28, 2015; Xinhua News, May 20, 2019). But an unknown portion comprises what can only be described as political censorship—suppressing outbursts of criticism or emotion while maintaining a steady supply of positive messages about China, its government, and the Communist Party.[9] With the ascendancy of CACs, the CCP has cracked down on “internet rumors”—a euphemism for messages that are sensitive or damaging to its interests; posts that inappropriately feature China’s national anthem or the likenesses of Party officials; and those that promote “non-mainstream views on marriage and love” (New York Times, January 2, 2019; Xinhua News, January 10, 2019).[10] As the following figure indicates, the majority of “illegal and harmful” posts reported to CACs are from Sina Weibo and Baidu.

Public Security Bureaus also play a major role in deleting web content. For most of the early 2000s, PSBs nationwide worked to construct the “Golden Shield” project (金盾工程, jinmao gongcheng), a public opinion monitoring system designed to provide internet police maximum visibility into the habits of China’s netizens (Human Rights Watch, August 18, 2017). Although most work on the project was completed by 2008, some budget documents indicate that PSBs are still purchasing and upgrading Golden Shield equipment in a “Third Phase” of the project designed to merge users’ social media history with other information, such as license plate databases, CCTV camera feeds, and financial records (Shenzhen Municipal PSB, May 18, 2017; Jianli County PSB, June 11, 2020). In 2017, for example, the PSB in Shenzhen planned to spend more than $6 million on various types of Golden Shield network equipment, including packet switching devices and data storage servers (Shenzhen Municipal PSB, May 18, 2017). Due to increased demand, the value of China’s nationwide market for public security network monitoring equipment has only grown after the completion of Golden Shield, and may now exceed $12.8 billion (Sealand Securities, January 26, 2016). The Ministry of Public Security budgeted more than $52 million for “informatization construction” in 2019 alone (MPS, 2019).

Conclusion

Although the Communist Party is working to leverage big data and artificial intelligence to streamline its public opinion monitoring (State Information Center, 2016; China Brief: May 15, 2020, October 16, 2020), China’s censorship apparatus is primarily sustained by an extensive network of Cyberspace Affairs Commissions, Public Security Bureaus, and increasingly, content reviewers employed directly by social media platforms (CitizenLab, May 7, 2020). Many Party committees today consider online public opinion to be “the top priority of propaganda and ideological work,” and collectively provided their CACs and PSBs with at least $6.6 billion in 2020 (Zhejiang University, January 1, 2017). Moving forward, those looking to better understand Chinese censorship should pay special attention to the role of Cyberspace Affairs Commissions, as well as efforts by Chinese internet companies to step up proactive censorship on their platforms.

The author is especially grateful to Dakota Cary, Andrew Imbrie, Ben Murphy, Igor Mikolic-Torreira, and Lynne Weil for their suggestions on style and content.

Ryan Fedasiuk is a Research Analyst at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET). His work focuses on military applications of emerging technologies, and on China’s efforts to acquire foreign technical information.

Notes

[1] See: Yik Chan Chin, “Internet Governance in China: The Network Governance Approach,” in Wang, Z. & Pavlićević, Dragan (eds) China into the New Era, Routledge Press, January 17, 2019, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3310921; Gary King, Jennifer Pan, and Margaret E. Roberts, “How Censorship in China Allows Government Criticism but Silences Collective Expression,” American Political Science Review May 2013, https://gking.harvard.edu/files/censored.pdf; and Dahlia Peterson, “Designing Alternatives to China’s Repressive Surveillance State,” Georgetown University Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET), October 2020, https://cset.georgetown.edu/research/designing-alternatives-to-chinas-repressive-surveillance-state/.

[2] For a related, previous report auditing the Communist Party’s budget for United Front work, see Ryan Fedasiuk, “Putting Money in the Party’s Mouth: How China Mobilizes Funding for United Front Work,” China Brief, the Jamestown Foundation, September 16, 2020, https://jamestown.org/program/putting-money-in-the-partys-mouth-how-china-mobilizes-funding-for-united-front-work/.

[3] Budget documents were collected for 2020 or the last year available. About three-quarters of budget figures were from 2020, and all others from 2019. All dollar values are in nominal USD as of December 1, 2020.

[4] The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology’s Cyber Security (19th) Bureau (网络安全管理局) is primarily concerned with detecting network vulnerabilities and cyberattacks, but part of its mission is technically still also concerned with monitoring China’s “internet ecology.” It operates a national internet reporting center, which is being gradually phased out in favor of one operated by the Central CAC.

[5] More than three-quarters of budget documents are from 2020; all others were published in 2019. For further details about the documents reviewed for this analysis, please reach out to the author directly.

[6] These line items are the most granular units of analysis afforded by CCP budget documents. While it is unclear how funds are distributed within, for example, “cyberspace affairs,” some localities offer enough detail to confirm that “public opinion guidance” is a key priority.

[7] KnowleSys (乐思) is one of the largest internet surveillance and sentiment analysis companies in China, and holds contracts with the Ministry of Public Security, the Central Propaganda Department of the CCP, the People’s Armed Police, and major state-owned enterprises and internet service providers.

[8] Statistics compiled by author, based on monthly “Acceptance of National Online Reports” (全国网络举报受理情况) announcements from the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission, January–October 2020. This figure is surely an underestimate, as it excludes posts removed proactively. See also: Jason Q. Ng, “Politics, Rumors, and Ambiguity: Tracking Censorship on WeChat’s Public Accounts Platform,” University of Toronto CitizenLab, July 20, 2015, https://citizenlab.ca/2015/07/tracking-censorship-on-wechat-public-accounts-platform/.

[9] See: Jason Q. Ng, Blocked on Weibo: What Gets Suppressed on China’s Version of Twitter (And Why), The New Press, August 27, 2013, https://www.amazon.com/Blocked-Weibo-Suppressed-China%C2%92s-Version/dp/159558871X.

[10] Recent reporting has similarly underscored how the CCP censored content related to the spread of COVID-19 as part of a broader campaign to downplay the threat of the virus. See: Raymond Zhong, Paul Mozur, Jeff Kao and Aaron Krolik, “No ‘Negative’ News: How China Censored COVID-19,” New York Times, December 19, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/19/technology/china-coronavirus-censorship.html; Jessica Batke and Mareike Ohlberg, “Message Control: How A New For-Profit Industry Helps China’s Leaders ‘Manage Public Opinion,’” ChinaFile, December 20, 2020, https://www.chinafile.com/reporting-opinion/features/message-control-china.