Is the Growth of Sino-Nepal Relations Reducing Nepal’s Autonomy?

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 5

By:

Introduction

Commonly held economic theory generally suggests that foreign aid benefits the recipient. But so far, China’s bilateral relations with Nepal—which are based upon generous pledges of foreign direct investment (FDI)—have created a power imbalance. China’s outsized influence in Nepal was most recently highlighted by overt Chinese involvement in a recent constitutional crisis that split the ruling Nepal Communist Party (NCP). A week after Prime Minister Khagda Prasad Sharma Oli dissolved the Parliament on December 20, a delegation led by Guo Yezhou, vice minister of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) International Liaison Department visited Kathmandu to “assess the situation” and mediate discussions between conflicting factions within the NCP (Firstpost, December 29, 2020). China’s growing influence in Nepal and across the Himalayan region more broadly is closely tied to its wider economic, security, and foreign policy priorities (China Brief, November 12, 2020). For Nepal, the unprecedented deepening of the bilateral relationship has raised serious concerns about its ability to maintain political and economic autonomy.

Beijing’s Progressive Inroads and Influence Strategies in Nepal

The Sino-Nepalese relationship has been predicated upon foreign direct investment deals, capacity-building measures and diplomatic support in international forums. A 2019 report by AidData highlighted “financial diplomacy,” including infrastructure financing, budget support, debt relief, and humanitarian assistance as being a key element of China’s public diplomacy toolkit in the South and Central Asian region.[1] China has led FDI pledges to Nepal for the last five years. In October 2019, a top U.S. diplomat warned, “As Chinese influence has grown in Nepal, so has the government of Nepal’s restrictions on the Tibetan community,” signaling growing international concerns over the China-Nepal relationship (Kathmandu Post, October 23, 2019). Just as border tensions between China and India turned violent last June, Nepal rekindled a longstanding cartographic dispute with India that some on the Indian side saw as a signal of its growing closeness with China. The Nepalese government passed a new political map that marked the Indian territories of Kalapani, Lipulekh and Limpiyadhura as Nepalese territory. One Indian government official described the act as drawing “red lines on the map to serve [Nepal’s] domestic and foreign interests” (Hindustan Times, June 10, 2020).

China and Nepal signed their first bilateral agreement on economic aid in 1956, and the Nepalese Foreign Ministry has said that Chinese financial and technical aid to Nepal dates back to the mid-1980s (Nepal Ministry of Foreign Affairs, February 2019). The Kathmandu-based political analyst Chandra Dev Bhatta has argued that China began scaling up its influence efforts in a notable way after 2008, when Nepal transitioned from a monarchy to a federal democratic republic. “Reality is such that after the political change…China has strongly positioned itself in Nepal and scaled up its engagement in more than one way. In the past, one could notice China’s involvement in the development of infrastructure but not in soft areas. Of late, China has been penetrating in[sic] Nepali politics as well as in society,” Bhatta said (The Diplomat, May 22, 2020).

China overtook India as Nepal’s largest FDI partner in 2014. Last year, Chinese state media reported that Chinese investors pledged more than $220 million worth of FDI to Nepal during the fiscal year 2019-2020, which more than doubled the previous year’s figures ($116 million) even during the Covid-19 pandemic. Chinese FDI accounted for two-thirds of Nepal’s total committed FDI during the reporting period (China Daily, September 9, 2020). Part of this growth was due to the passing of a 2019 Foreign Investment and Technology Transfer Act designed to streamline the process for approving foreign investments in key sectors such as hydropower, construction, telecommunications, agriculture and mining. Foreign analysts have observed that although Chinese state investments have generally targeted hydropower and transportation, investments from the private sector have mostly targeted micro-enterprises—with a couple of notable exceptions in the cement industry (Stimson Center, November 12, 2020).

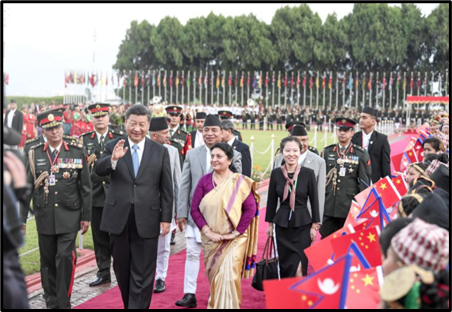

Following Nepal’s official joining of China’s ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI) in 2017, the BRI has also emerged as a new instrument for deepening bilateral ties between Beijing and Kathmandu. Initial agreements for a Trans-Himalayan Multi-Dimensional Connectivity Network—to encompass both infrastructure projects and cultural exchanges—were signed. (Nepal Ministry of Foreign Affairs, June 21, 2018). In 2019, Xi Jinping paid a state visit to Nepal, marking the first time that a Chinese president visited the country in 23 years. During Xi’s visit, the two countries elevated their relationship to a “strategic partnership,” creating the impetus to prepare work on projects such as a cross-border railway linking the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) with Kathmandu and a China-Nepal Friendship Industrial Park in Jhapa, eastern Nepal (China Daily, December 24, 2020).

Expanding railway ties between China and Nepal would promote trade and increase Nepal’s economic capacity (see image below). China has promised to allow Nepal access to six dedicated border transit points—Rasuwagadhi, Kodari, Yari, Kimathanka, Olangchungola and Nechung—and access to sea ports in Tianjin, Shenzhen, Lianyungang and Zhanjiang and land ports in Lanzhou, Lhasa and Shigatse, which could help to balance landlocked Nepal’s economic reliance on India (My República, March 7). In 2015, the Nepalese blamed trade disruptions that impacted food and energy supplies on an Indian “blockade,” which had later influenced the leadership’s shift towards China (The Diplomat, February 1, 2017). Local analysts have also observed that, alongside the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), such investments could also aid in either increasing access to or circumventing the massive Indian economy, depending on how bilateral China-India relations develop (Kathmandu Post, August 6, 2020).

Nepal and China have also increased security cooperation, with China opening up a training academy for the Armed Police Force (APF) that guards border districts with Tibet in 2014 and holding counterterrorism drills between the Nepal Army and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in for the first time in 2016 (Reuters, December 26, 2014; My República, December 29, 2016).

Bilateral cooperation in fields such as construction, education, agriculture and hydropower has chipped away at India’s traditional sphere of influence in Tibet as ongoing border and water disputes have also soured the India-Nepal relationship. In light of this, Nepal has prioritized developing economic ties with China (ORF, October 3, 2018). But closer China-Nepal ties have also had benefits in the international realm. For the past two years, Nepal has supported China’s position on Xinjiang at the United Nations Human Rights Council (China Brief, December 31, 2019; The Diplomat, October 9, 2020). Nepal also supported China on the status of Hong Kong last year (PRC Embassy in Nepal, June 20, 2020).

China’s Geo-Strategic Goals in Nepal

Weaken Indian Influence

China seeks to fade away India’s traditional close ties with Nepal. This strategy has received some pushback inside Nepal. Most recently, the former Nepalese Prime Minister Baburam Bhattarai told Indian media “we have historical relations, closest economic interactions, cultural and social affinity, [and] geographically also our people’s movement is towards India [rather] than China. So, in that sense, China can never be a replacement of India for Nepal” (The Print, March 3). This is reflected in trade numbers: Nepal imports more than two-thirds of its trade goods from India, and only around 14 percent from China. India also receives 60 percent of total exports from Nepal, compared to China’s 2 percent. (Economic Times, June 16, 2020).

The revitalization of border tensions between China and India last year also prompted Beijing’s interest in Nepal’s historic military ties with India: a legacy of colonialism has meant that around 30,000 Nepalese Gurkha troops currently serve in the Indian army and are often deployed to frontline positions along the border. More than one million Gurkha veterans live in Nepal. Last year, Indian intelligence reported that Beijing allegedly funded a report from the China Study Center in Nepal, which one former Indian army officer called an “attempt by China to fish in troubled waters” (India Today, August 17, 2020). Nepalese media noted that China has not lodged any formal objection to India’s use of Gurkha soldiers (The Annapurna Express, June 23, 2020).

Protect the Communist Establishment

Beijing’s overt involvement in the Nepalese political crisis which began last spring has not gone without notice. The Chinese Ambassador acted as a mediator in an intra-party rift of the Nepal Communist Party after senior party leaders confronted Prime Minister Oli in April 2020. After Oli moved to dissolve parliament and call for fresh elections in April and May, a high-level team from Beijing was dispatched to meet with Nepal’s fractured leadership and reportedly the opposition as well (The Diplomat, December 28, 2020). While an official spokesperson from China’s foreign ministry said only that China wanted the relevant parties to “properly handl[e] internal differences and [work] towards political stability and the country’s development,” one European diplomat put it more bluntly: “they are clearly concerned about the massive investments they have pledged…they are shocked as to how Oli could make a bold political move without prior consultations” (Reuters, December 31, 2020).

Maintain the Geopolitical Imperative of the BRI

After partnering with Pakistan, President Xi Jinping is keen to utilize the strategic location of Kathmandu to serve BRI objectives, which range from developing infrastructure to creating deeper cultural and political connections. Newer BRI-linked programs such as the Health Silk Road and the Digital Silk Road could expand China-Nepal ties even more in the future; Beijing has been active in expanding its vaccine aid to Nepal even as land trade between the two countries has been effectively halted by the ongoing pandemic (My República, March 2; Kathmandu Post, February 1). It is clear that Beijing intends to make the best use of Nepal’s geostrategic position to reach out to other parts of the region. Developments including Nepal’s dispute with India over the redrawing of political maps and the halting of repair work on the Gandak dam are seemingly a part of Nepal’s effort to woo China.

Cement Regional Strength

Following the U.S. signing of the Tibetan Policy and Support Act of 2020 under President Donald Trump and the recent announcement that the Joseph Biden administration is committed to deepening relations with South Asian countries to maintain a “free and open” Indo-Pacific, geopolitical superpowers are increasingly focusing their attention on Nepal (SCMP, January 13; My República, March 11). In light of this, China may seek to press its advantage against its weaker neighbor. According to a report by the Nepalese government, China has encroached at 11 different locations –marking a total of approximately 33 hectares of land—belonging to Nepal as it builds up border infrastructure in the TAR and diverts river borders which have historically acted as a natural boundary (Times of India, June 24, 2020).

Conclusion

In December 2019 undercover Chinese agents led by Wang Xiaohong, the Director of the Ministry of Public Security, cooperated with Nepalese police forces to arrest and extradite 122 Chinese nationals from Kathmandu to Beijing. The Nepalese side was reportedly sidelined during the joint action and not even given access to any seized evidence—and the alleged criminals, whom the Chinese side said were suspected of having committed cybercrimes, were deported without a formal investigation. One legal advocate complained that the incident made a “mockery of Nepal’s legal system,” and another analyst worried that it could preface or even signal the de facto implementation of a highly controversial extradition treaty that would endanger Tibetan refugees in Nepal (Central Tibetan Administration, January 31, 2020). China’s well-publicized investments in Nepalese infrastructure and energy sectors have been paralleled by an increasingly awkward silence from the Nepalese government on sensitive topics such as infrastructure build-ups and territorial transgressions or questions surrounding Tibet.

Despite regular criticisms of Beijing at the hands of local media, academics and economists, China’s unchecked encroachment in the geopolitical affairs of Kathmandu has seemingly led to the gradual decline of Nepal’s political and economic autonomy. Nepal has so far avoided coming under the sway of foreign domination. Now the country’s leaders must decide on whether they aspire to uphold this history or dismantle it.

Dr. Dhanwati Yadav currently teaches Political Science at Dyal Singh College, Delhi University. She earned her PhD from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi.

Notes

[1] See: Custer, S., Sethi, T., Solis, J., Lin, J., Ghose, S., Gupta, A., Knight, R., and A. Baehr, “Silk Road Diplomacy: Deconstructing Beijing’s toolkit to influence South and Central Asia,” AidData at William & Mary, December 10, 2019, accessed from https://docs.aiddata.org/ad4/pdfs/Silk_Road_Diplomacy_Report.pdf.