Implications of 2020 and 2021 Chinese Domestic Legislative Moves in the South China Sea

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 14

By:

Introduction

A new People’s Republic of China (PRC) Coast Guard Law (中华人民共和国海警法,Zhonghua renmin gongheguo haijing fa) caught regional and international attention at the beginning of the year (Vnexpress, January 30; Kyodo News, February 9; Inquirer, February 12; South China Morning Post, February 25). It is one of many notable legislative projects in the maritime and security domain that the Standing Committee of China’s 13th National People’s Congress (全国人大常委会,quanguo renda changwei hui) has deliberated and passed during the last year and a half.

Other projects include the revised People’s Armed Police (PAP) Law (人民武装警察法 (修改), renmin wuzhuang jingcha fa (xiugai)), the revised National Defense Law (国防法 (修改), guofang fa (xiugai)), the revised Maritime Traffic Safety Law (海上交通安全法(修改), haishang jiaotong anquan fa (xiugai)), and the Hainan Free Trade Port (FTP) Law (海南自由贸易港法, Hainan ziyou maoyi gang fa). Taking into account the timing of these various legislative moves, this article sheds light on Chinese leaders’ current approaches to maritime issues from a legal perspective and highlights implications for future territorial disputes between China and other stakeholder nations in the South China Sea.

Speeding Up the Building of a Maritime Superpower

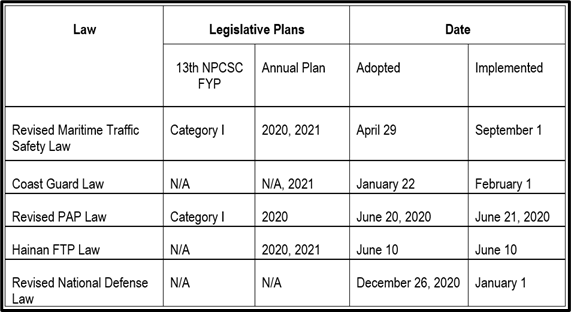

In September 2018, the 13th National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC) released its five-year legislative plan (13th NPCSC FYP) that sets the legislative agenda through 2023 (Gov.cn, September 7, 2018). Legislative projects included in this agenda are sorted into three categories of importance, with Category I projects given the most priority (see Table below). The 13th NPCSC also released its annual legislative plan for 2020 and 2021 on June 20, 2020, and April 21, respectively (Npc.gov.cn, June 20, 2020; Npc.gov.cn, April 21). The Coast Guard (CCG) Law, the revised National Defense Law and the Hainan FTP Law were not listed in the 13th NPCSC FYP, and neither the CCG Law nor the National Defense Law was included in the 2020 agenda. All were deliberated and adopted within the past year and a half.[1]

China has accelerated updates to key legislation in the security domain to “perfect” (完善, wanshan) its maritime legal system.[2] This could be the result of perceptions of rapid changes in the global and regional strategic environment, as evidenced by an “explanation” (说明,shuoming) provided by the Central Military Commission (CMC), the body that drafted and submitted the CCG Law, wherein it emphasized that China’s “struggle to protect maritime rights is facing a severe and complex situation” (Npc.gov.cn, October 13, 2020). An explanation for the revision to the National Defense Law highlighted that “the world’s strategic structure has profoundly evolved, international strategic competition is on the rise, and global and regional security issues continue to increase” (Npc.gov.cn, October 13, 2020).

Furthermore, the 14th Five-Year Plan (14th FYP) released in March includes a call for “situation study, risk prevention, and legal struggles” (Xinhua, March 13), which the international relations expert Zhu Feng (朱锋) has suggested shows China’s rising sense of crisis over the South China Sea (South China Morning Post, March 11). At the same time, as is also clearly stated in the explanations and the 14th FYP, the revision and adoption of these laws are necessary legislative moves to maintain “the internal coordination and unity of the legal system,” by enabling different agencies to work together, speeding up maritime development, and accelerating the building of a maritime power (海洋强国,haiyang qiangguo) (Npc.gov.cn, October 13, 2020; People’s Daily, March 5; Xinhua, March 13).

Maintaining and Increasing Legal Ambiguity

The CCG Law and the revised Maritime Traffic Safety Law reflect that the Chinese leadership is maintaining a policy of ambiguity with respect to maritime claims. The CCG Law applies to “the Chinese Coast Guard Organization conducting the activities of maritime rights protection and law enforcement in and above the PRC’s jurisdictional waters” (italics added) (管辖海域, guanxia haiyu) under Article 3. It is worth noting that in Article 74, item 2 of the initial draft released in November 2020, “jurisdictional waters” refers to China’s “internal seas, territorial sea, contiguous zone, exclusive economic zone, continental shelf, and other sea areas under the PRC’s jurisdiction” (italics added) (中华人民共和国管辖的其他海域,Zhonghua renmin gongheguo guanxia de qita haiyu). This clarification was removed from the final version of the CCG Law, leaving the term “jurisdictional waters” undefined.

Following the same pattern, Article 2 of the first draft revision to the Maritime Traffic Safety Law stipulated that “navigation, berthing, operations and other activities related to maritime traffic safety in the coastal waters (沿海水域,yanhai shuiyu) of the PRC shall abide by this law.” The term “coastal waters” was defined, as “internal seas, territorial sea and other sea areas under the jurisdiction of the PRC” under Article 115. The final version replaced the term “coastal waters” with “the PRC’s jurisdictional waters,” but the law provides no definition of this term.

Some Chinese writers have suggested that “jurisdictional waters” could indicate waters China claims that are controlled by other countries,[3] whereas the “other sea areas” could refer to all of the sea areas inside the “nine-dash line” (China U.S. Focus, May 15, 2012). Others argue that marine areas within China’s jurisdiction include not only the waters over which China is entitled to exercise jurisdiction under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)—namely, internal waters, territorial sea, contiguous zone, exclusive economic zone and the waters of the continental shelf—but also those over which China enjoys historic rights.[4]

A 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration concluded that China’s claim to historic rights is incompatible with UNCLOS to the extent that it exceeds the limits of China’s maritime zones (Permanent Court of Arbitration, July 12, 2016). Throughout 2020 and early 2021, 10 claimant and non-claimant countries submitted diplomatic notes to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (UNCLCS) to reaffirm their legal position that China’s claims of “historic rights” over the South China Sea lack international legal basis and do not comply with UNCLOS provisions (UN.org, January 29).

China’s use of the terms “jurisdictional waters” and “other sea areas” is not new. However, the fact that China continues to use such ambiguous terms suggests that this vague language provides China with the flexibility to modify the legal basis of its maritime claims in the South China Sea and justify its maritime claims beyond UNCLOS rules.[5] These terms have been made even vaguer in China’s new maritime domestic laws, reflecting the state’s “growing concerns over the South China Sea” (South China Morning Post, March 11), and suggesting China’s intention to perhaps exploit such ambiguity in future so-called “legal struggles” (Xinhua, March 13).

Strengthening Coordination Among Organizations

The new CCG Law and the revised PAP Law have created a legal basis to unify supervision in the maritime domain and strengthen internal coordination and cooperation following reforms to both organizations in 2018. According to Article 2 of the revised PAP Law, the PAP now sits under “the centralized and unified leadership of the Party Central Committee and the Central Military Commission.” The mission of “maritime rights protection and law enforcement” (海上维权执法,haishang weiquan zhifa) has been added to the PAP’s mandate under Article 4 and 41.

Notably, the PAP Law enables further integration of the PAP with the military (Nikkei, June 21, 2020). Article 10 stipulates that the PAP, including the CCG, can “participate jointly in non-combat military operations such as emergency rescue, maintaining stability and handling emergencies,” and even “conduct joint training exercises” with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Article 8 of the CCG Law similarly lays out the establishment of a “cooperation and coordination mechanism” (协作配合机制,xiezuo peihe jizhi) between the CCG and relevant organizations, which was absent from the initial draft. Article 53 and 58 further provide that relevant organizations are required to facilitate the CCG’s law enforcement activities through logistics support and information sharing.

PLA military officers have long called for authoritative domestic laws to enable the PLA Navy, the CCG and the maritime militia to work together to defend the country’s national interests.[6] They have argued that China’s sea services should “have the ability to leverage joint management and joint defense activities […] in order to jointly attack various types of illegal activity […].”[7] The new CCG Law and the PAP Law revision may go some way towards legalizing this.

Speeding up Maritime Development

The new Hainan FTP Law and the revised National Defense Law suggest Chinese leaders’ emphasis on speeding up maritime development (including maritime economic development) and protecting what China calls its “development interests” (发展利益,fazhan liyi).

The local government of Hainan Province is an active participant in defining and asserting China’s sovereignty and maritime rights in the South China Sea.[8] Sansha City, which was established as a prefecture-level city in Hainan Province in July 2012, has jurisdiction over several disputed “islands and reefs” and “sea areas” in the South China Sea.

Hainan’s local marine economic plans were accepted as part of the national maritime development strategy and included in the 13th FYP (2016–2020) for marine economic development (Sina.com.cn, May 5, 2015; Ndrc.gov.cn, March 16, 2016). Articles 38 and 39 of the Hainan FTP Law echoed earlier drives to emphasize tourism’s developmental potential,[9] as well as the aim to consolidate China’s position in the South China Sea through maritime economic development.

The term “development interests” was included in the revised National Defense Law for the first time and appears in four important provisions. First, Article 2 states that development interests are to be protected by military activities. Second, the building of strong national defense capabilities is required to meet the demands of China’s development interests according to Article 4. Similarly, the size of China’s armed forces must be “compatible with the need to safeguard China’s sovereignty, security, and development interests” under Article 25. Finally, Article 47 adds “development interests” as a legitimate reason for the mobilization of China’s armed forces.

Despite the inclusion of “development interests” to the law’s key contents, the term is undefined. The term “development interests” remains legally undefined, but could feasibly include territorial disputes in the South China Sea and China’s so-called “maritime rights and interests” within its scope. Understood this way, any perceived threat to China’s maritime development interests could be used to justify military action.

Conclusion

The implementation of the abovementioned maritime and security laws in the South China Sea, as well as the extent to which they might challenge regional and global legal norms, remains to be seen. Some preliminary conclusions can be drawn based on the above analysis. First, the new CCG Law, the revised Maritime Traffic Safety Law and the anticipated Ocean Basic Law will continue to adopt the strategic use of ambiguous terms as an instrument of legal warfare to bolster the legitimacy of Chinese maritime claims in the South China Sea.[10] Second, the domestic legislative project of perfecting the maritime legal system promotes coordination and cooperation among law enforcement agencies and the PLA. Such actions serve to legalize unilateral maritime law enforcement activities at least under China’s own legal system, as well as providing the means to conduct such activities more effectively. Third, the Chinese leadership has taken steps to speed up maritime development and safeguard so-called “development interests” since the passing of the 2018-2023 NPCSC legislative agenda. These moves also indicate the development of a more comprehensive legal, economic and military framework to accelerate the building of China as a maritime power. In the context of rising tensions in the South China Sea and strategic competition between China and the U.S., the building and implementation of maritime power are seen as both ends and means in the process of expanding China’s normative and physical control in the South China Sea.

Lan Anh Nguyen Dang is a doctoral candidate at the Graduate School, Faculty of Business, Economics and Social Sciences (WiSo), at the University of Hamburg. She is also a researcher at the Institute for Chinese Studies, Vietnamese Academy of Social Sciences.

Notes

[1] Full-texts (of the initial drafts and final versions) as well as explanations are posted on the website NPC Observer. For the revised People’s Armed Police Law, see at https://npcobserver.com/legislation/peoples-armed-police-law/; the revised National Defense Law, see at https://npcobserver.com/legislation/national-defense-law/; the CCG Law, see at https://npcobserver.com/legislation/coast-guard-law/; the revised Maritime Traffic Safety Law, see at https://npcobserver.com/legislation/maritime-traffic-safety-law/; the Hainan FTP Law, see at https://npcobserver.com/legislation/hainan-free-trade-port-law/.

[2] See: Isaac Kardon, “China’s maritime interests and the law of the sea: Domesticating public international law”, in John Garrick and Yan Bennett (eds.), China’s socialist rule of law reforms under Xi Jinping, London: Routledge (2016), pp.179-180.

[3] See: Academy of Military Science [军事科学院], “The Science of Military Strategy [战略学2013],” Beijing: Military Science Press, (2013), p.210.

[4] See: Ma Xinmin, “China and the UNCLOS: Practices and policies”, The Chinese Journal of Global Governance, vol. 5, no. 1 (2019), pp.12-13.

[5] See: Sarah Lohschelder, “Chinese domestic law in the South China Sea”, New Perspectives in Foreign Policy, Issue 13 (Summer 2017), p.34; Gregory Poling, The South China Sea in focus: Clarifying the limits of maritime dispute, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, (2013), p.2.

[6] See: Wu Jianhong (吴建红), Huang Chunyu (黄春宇), and Liu Changlong (刘昌龙), “Thoughts on advancing ocean defense construction work in the new situation [新形势下推进海防建设工作的思考],” National Defense [国防], no. 12 (2015), p. 71.

[7] Ibid., p.72.

[8] See: Li Mingjiang, “Hainan Province in China’s South China Sea policy: What role does the local government play?”, Asian Politics & Policy, vol. 11, no. 4 (2019), pp. 623-642.

[9] See: China National Democratic Construction Association, Hainan Provincial Committee, The United Front Work Department of CPC Central Committee, “Recommendations to guarantee the safety of Sansha Tourism [关于加强三沙旅游安全保障的建议]”, quoted and translated by Rowen I. (2018) “Tourism as a territorial strategy in the South China Sea”, in Spangler J., Karalekas D., Lopes de Souza M. (eds) Enterprises, localities, people, and policy in the South China Sea, Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, (2018), p.65.

[10] See: Douglas Guilfoyle, “The rule of law and maritime security: Understanding lawfare in the South China Sea”, International Affairs, vol. 95, no. 5 (2019), p.1015.