The Sino-French Relationship At 60: China’s Losing Bet On A Reset

Publication: China Brief Volume: 23 Issue: 22

By:

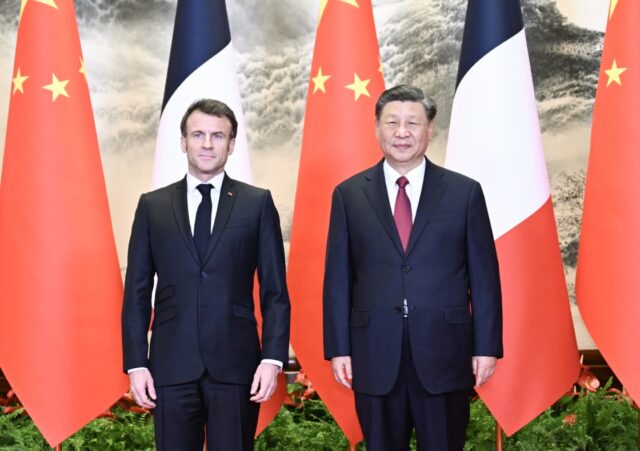

Against a background of increasingly fraught relations with the European Commission, China has been doubling down on its outreach to member states, with France chief among them. The two countries have been gearing up to the 60th anniversary of their bilateral relationship in January 2024 with a flurry of diplomatic exchanges. These have included high-level visits by President Emmanuel Macron in April, Economic Minister Bruno Le Maire in July, diplomatic adviser Emmanuel Bonne in late October, and most recently Foreign Affairs Minister Catherine Colonna (FMPRC, November 22). On the Chinese side, Premier Li Qiang traveled to Paris in June to take part in the Summit for a New Global Financing Pact. However, this year also saw Paris deal some blows to China’s economic ambitions, with Macron being one of the driving forces behind Brussels’ ongoing anti-subsidy investigation into China-made electric vehicles and revamping its own EV purchase credits to exclude Chinese-made models (Service Public, October 10).

During Bonne’s visit, Wang Yi framed his expectations for the anniversary in no uncertain terms, calling on China and France to “revisit the original intention (重温建交初衷)” of their bilateral ties and “consolidate and reset (巩固和再出发) the relationship” (FMPRC, October 30). Paris’ appetite for meeting Beijing halfway in “resetting” the relationship is far less certain. Most likely, China’s lofty ambitions for a reset will be met with more ambiguity from France, continuing its diplomatic outreach to safeguard economic opportunities in China, all the while pushing for more assertive policies within Brussels to achieve its vision of “strategic autonomy.” While some scholars are not entirely immune to the “dual-faced (两面性)” nature of French diplomacy (Fudan Development Institute, March 2), a prevalent view—or hope—among officials in Beijing is that Macron’s vision of strategic autonomy is primarily about asserting an independent foreign policy from the United States. However, in reality, strategic autonomy also informs France’s own de-risking agenda toward China.

France as a “major independent country”

France’s commercial linkages play a key role in France’s strategic importance to Beijing. While France’s trade ties with China are not as large as Germany’s, the country is still is a top exporter of industrial products in strategic fields, principally aeronautics. French firm Safran, for example, provides engines for COMAC’s C919, China’s answer to the Boeing 737, as well as a majority of its helicopters (Safran website, accessed November 28). Airbus has jointly developed helicopters with the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC) and has most recently sold 50 multi-role H160 models to Chinese lessor GDAT (Airbus, March 26, 2014; Airbus, April 7). In terms of investment, France is part of the “chosen few” countries—which include the four European states alongside Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK—that constitute more than 80 percent of EU foreign direct investment into China (Rhodium Group, September 14, 2022).

Beyond commercial ties, France’s importance to Beijing also rests on its geopolitical positioning as a “major independent country (独立自主大国),” a term used quasi-systematically in recent diplomatic readouts. In January 1964, famously guided by “the weight of evidence and reason,” President Charles de Gaulle made France the first major Western country to recognize China, nearly a decade before the People’s Republic of China (PRC) would gain its seat at the United Nations. De Gaulle is reported to have said “there is something abnormal in the fact that we do not have relations with the most populous country in the world on the pretext that its regime does not please the Americans” (L’Obs, January 28, 2013). From the outset of the relationship, Beijing has held expectations for Paris to serve as a powerful troisième voie against deeper alignment with the United States.

Macron borrows from de Gaulle’s pragmatism, has a heavy dose of skepticism towards the United States, and has influence within the EU. Chinese policymakers and shapers thus see in Macron an attractive partner for engagement. The cornerstone of France’s appeal to Beijing’s diplomatic agenda is Macron’s desire for “strategic autonomy.” While the concept of “strategic autonomy” entered Brussels parlance in 2013, Macron elevated its importance during a 2017 speech at the Sorbonne (Elysee, December 26, 2017).

Although intended as a vision of a more capable and independent EU able to act autonomously in important policy areas, the concept of strategic autonomy has largely—and somewhat mistakenly—been framed by some Chinese academics and think tankers as a shield against deeper alignment with the United States. For example, Cui Hongjian (崔洪建), the director of the Department for European Studies at Peking University’s China Institute for International Studies, sees the EU as being divided between an “Atlantic faction” and a “strategic autonomy faction,” with Macron leading the latter (People’s Daily, May 27).

Strategic Autonomy, But En Même Temps… [1]

The best characterization of France’s China policy is not the pursuit of strategic autonomy, but rather the diplomacy of “en même temps.” Paris has continuously balanced economic and symbolic tilts towards China to serve its commercial interests, while also pushing policies in Brussels which clearly go against Chinese interest. During its Presidency of the Council, France formalized the European Commission’s International Procurement Instrument—a regulation it had fought for a decade to concretize (MEAE, June 22, 2022)- championed the beginning of talks on the Anti-Coercion Instrument (MEAE, March 28) and was a strong backer of the Foreign Subsidies Regulation. All three regulations are seen as the bedrock of the EU’s new toolkit to address China’s market-distortive practices. The blurriness of this approach, combined with the lack of a document clarifying the government’s China strategy, has led to repeated irritants with other diplomatic partners.

Macron’s “en même temps” diplomacy can be seen across recent developments. On the one hand, Macron’s visit in April saw a lengthy Joint Statement and a raft of economic agreements, notably in the aeronautical field, as well as highly controversial interview called on Europe not to be a “follower of the United States” (Les Echos, April 9). Framed under the auspices of strategic autonomy, the visit was perceived as a rousing success in Chinese diplomatic circles and fed into the Chinese narrative of France’s strategic autonomy pushing back against deeper US alignment (Global Times, April 8). Former prime minister Jean-Pierre Raffarin attended China’s Belt and Road Forum in Beijing in October, despite most other EU member states avoiding the summit (Xinhua, October 19). This constituted, in Beijing’s eyes, a powerful show of support. At the same time, Paris was one of the main backers of the EU Commission’s push for the anti-subsidy probe into China-made EVs and has also revamped its tax credit policy to exclude China-made models.

While the EU’s anti-subsidy probe will not be concluded for several months, most China-made models risk being excluded from France’s purchase credit for new EV purchases, starting from January 2024. Under the new policy, qualifying models will have to obtain sufficient points against a newly designed environmental framework. This framework considers not only the characteristics of the battery and model themselves but also the environmental impact of the materials used, the vehicle’s assembly, and the transportation process. This scoring system paves the way for broader adoption among member states, with Italy reportedly considering taking action next (Reuters, 2 October 2023). Country-agnostic in its design, the framework could also discourage purchases of EV exports from other trade partners like South Korea, the United States, or Japan. It may also discriminate against American and European models that are manufactured in China, like the popular Dacia Spring. But to Beijing, this may read as Paris following in the footsteps of the United States’ Inflation Reduction Act, which makes EV credits conditional on United States-manufactured content. At a time when China’s overall economy and trade activity are slowing, its EV sector has stood out as a relative bright spot, making France’s trade defense action appear as a tough blow on to its export-driven model.

Macron’s pushback against Chinese EV exports is couched in the same language of “strategic autonomy” that Chinese officials typically welcome and see as a positive item in the bilateral relationship. While creating barriers to exports, France hopes to attract more investment from Chinese battery manufacturers in order to build up its strategic autonomy in the green transition. The Northern “Battery Valley” (Economy Ministry, May; Hauts-de-France, accessed November 27) already counts announced plants by Shanghai-headquartered Envision AESC and a joint venture between XTC New Energy Materials Xiamen Co. and Orano. However, some Chinese commentors are beginning to take note and raise concerns. Some are suggesting Chinese firms should not follow through with investment plans, as the “hostile policies” of France may bring increasing scrutiny of Chinese firms (Auto Magazine, September 27).

For now, Beijing has responded by announcing restrictions (which take effect in December) on graphite products—key inputs to EV batteries—sending a clear signal it can leverage its dominance in the critical minerals and raw materials supply chain to thwart western industrialization plans by withholding upstream exports (MOFCOM, October 20). Despite scholars acknowledging France’s role in the EU’s turn against Chinese EVs (Shijie Zhishi, October 26), China has avoided direct retaliation against French actors for now. French luxury and cosmetics retailers—which are usually on the frontlines when tensions do arise in the bilateral relationship—have not raised alarm bells thus far. A Global Times article commenting on Colonna’s visit to Beijing noted, “Although the European anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese electric vehicles (EVs) is considered a negative move in China-EU trade cooperation, it won’t fundamentally affect the development of the bilateral ties between China and France” (Global Times, 23 November). This suggests Beijing may be trying to preserve the relationship ahead of the 60th anniversary in January and beyond.

Somewhat ironically, in the recent Chinese readout of Li Qiang’s meeting with Colonna, the Chinese side expressed hope Paris would help temper the EU’s China policy and “actively encourage the European side to uphold the spirit of free trade” (FMPRC, 24 November). For Paris, Beijing’s export controls will be perceived as an affront to its ambitions for strategic autonomy—especially as it tries to build its “Battery Valley” in its northern regions. It will also serve to quicken the pace of de-risking and other trade-defense-related policies in Europe.

Looking towards the future

Come January 2024, Paris may celebrate the 60th anniversary of bilateral ties with pomp and circumstance—and a potential visit by President Xi Jinping at some point during the year—but Beijing’s hoped “return to the original intention” of the relationship is unlikely to happen. Beijing might wish to turn back the clock to a time where EU-China relations were not as fraught, but tapping Paris to do so is a false bet. Paris will continue its diplomatic engagement with Beijing to seek its cooperation on global challenges like climate change and international crises like the Ukraine-Russia and Israel-Hamas conflicts, while also trying to preserve the economic interests of French firms in China for as long as possible. At the same time, guided by Macron’s vision for strategic autonomy, and its attendant ambiguity, Paris will be equally active within Brussels to build up new defensive mechanisms targeting China’s growing footprint in critical sectors.

Notes

[1] At the risk of explaining the joke, the phrase “en même temps” (at the same time) has become a common derisory epithet for Macron, who frequently uses it to argue for and then against a case (See for instance: Institut Montaigne, April 21; France 24, October 19, 2022).