Kazakh Official’s Conviction Offers Hope for Combating Domestic Violence in Central Asia

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 93

By:

Executive Summary:

- The issue of domestic violence in Central Asia has increasingly gained attention since a former Kazakh economic minister tortured and killed his wife and was convicted of murder, inspiring reform movements throughout Kazakhstan.

- Corruption plays a significant role in the condoning of domestic violence in Kazakhstan, with government officials and the authorities failing to provide reliable protection for victims, leading to distrust in the government.

- The societal acceptance of domestic violence in Central Asia correlates to the normalization of violence in society, which can lead to further unrest, increased militarization, and violent repression.

On May 13, former Kazakh Economic Minister Quandyq Bishimbaev was sentenced to 24 years in prison for the murder of his wife, Saltanat Nukenova. He was found guilty of torture, murder with extreme violence, and repeatedly committing serious crimes (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, May 13). Sources close to the couple reported that this was not the first time Bishimbaev had been physical toward Nukenova. He did not face any consequences for the previous occurrences, however (Orda, November 12, 2023; Eurasianet, January 9). Nukenova’s death immediately became a national tragedy, sparking outrage across the country and bringing the issue of domestic violence against women and the leniency of law enforcement in these cases to the forefront of public debate. Domestic violence is not new to Central Asia and is rooted in deeper societal issues, including the wide acceptance of violence and corruption. Nukenova’s status as the wife of a bureaucrat elevated her story to the masses and has inspired calls for government reforms and regional cooperation in protecting against domestic violence in Kazakhstan and throughout the region.

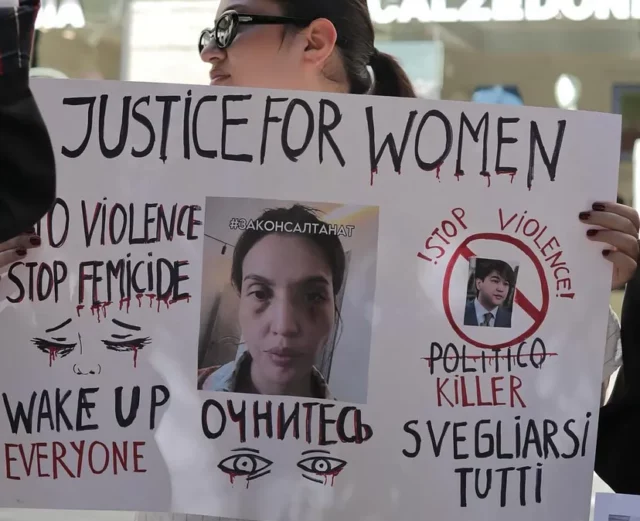

Since November when Bishimbaev’s case first came to light, women’s rights activists have protested in Kazakhstan and the wider region calling for change (Human Rights Watch, November 27, 2023; Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, March 8; Radio Azattyq, April 8). Additionally, countless women have come forward about the abuse they endured from current and former Kazakh government officials (The Times of Central Asia, June 13). The discontent and instability fueled by domestic violence often leads to societal unrest in Central Asia. In Kazakhstan, The Astana Times reported that one in six women has been subjected to domestic violence (The Astana Times, November 24, 2023). Furthermore, according to the United Nations, about 400 women are killed every year in Kazakhstan due to domestic violence (KTK.kz, March 3, 2018; Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, November 22, 2023). The Gender Social Norms Index from the UN Development Programme reports that at least 90 percent of women experience gender bias across Central Asia, including an undervaluing of women’s capabilities and rights(UN Development Programme, October 19, 2023).

Corruption plays a significant role in condoning domestic violence in Kazakhstan. In 2017, former President Nursultan Nazarbayev decriminalized domestic violence and downgraded it to an administrative offense in the name of preserving traditional family values (Online.zakon.kz, accessed June 13). In April this year, however, due to discontent over Nukenova’s death, current President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev signed a law that criminalizes domestic violence and toughens punishments (T.me/aqorda_resmi, April 15; The Times of Central Asia, April 16). Local law enforcement often do not offer proper information about what victims are entitled to when they receive reports, leaving many women ignorant of their own rights (Human Rights Watch, October 17, 2019). In addition, women’s rights groups in Kazakhstan have reported officers accepting bribes to facilitate “reconciliation” between abusers and victims (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, December 6, 2023).

Across the region, corruption and bribery are rampant in the police system (Development Asia, January 17; Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, January 30). Over the past two decades, Central Asian governments have organized their police forces to ensure that they would be able to “disperse any outbreaks of non-state violence” through increased repression. Aculture of bribery also contributes to a reluctance to go through bureaucratic procedures, such as arrests (Erica Marat, Policing Public Protest in Central Asia, 2014; Central Asian Analytical Network, March 2, 2021).

The systematic acceptance of domestic violence in the police system also comes in subtler forms. Only a third of women who experience domestic violence in Kazakhstan seek police intervention, and the punishment for domestic violence is often a fine of 25,250 tenge–101,000 tenge ($65–$260). One woman who filed a case against her husband questioned, “Why [does he have to pay] the state? … Turns out it is profitable for the government.” Additionally, the money used to pay the fine is often taken from the family budget, thus also negatively affecting the woman and rest of the family, not just the perpetrator . The corrupt system for “combating” domestic violence “effectively permits an abuser to pay for the right to abuse” and provides the government with an incentive to continue to condone domestic violence (Human Rights Watch, October 17, 2019; The Astana Times, November 24, 2023).

The limited number of women in Kazakhstan’s government means they often do not have the opportunity to advocate for themselves. Women comprise less than 20 percent of Kazakhstan’s parliament, with only 30 representatives. At the Dialogue of Women of Central Asia in June 2023, representatives discussed the region’s unique gender disparities, their deep roots in patriarchal norms, and how they contribute to the low number of women in politics. This disparity is directly related to the continuation of limited government support for victims of gender-based violence (The Astana Times, June 22, 2023; Vlast, November 16, 2023). Many conservative members of the government reduce domestic violence to “traditional family values,” blame women for “inappropriate behavior,” and seemingly do not understand the importance of addressing the issue (Vlast, November 16, 2023).

Societal acceptance of domestic violence as part of “traditional family values” often influences legislative decisions. In September 2023, Minister of Parliament Amantay Zharkynbek stated that the wives of men sentenced for domestic violence should also face the consequences of “provocation”—namely, that women must take responsibility for domestic violence committed against them (Kursive.media, September 27, 2023). In November 2023, Almaty Children’s Rights Commissioner Khalida Azhigulova, when speaking on how rampant domestic violence is in Kazakhstan, wrote on her Facebook page, “Rapists are in positions of high power: they beat their wives, children [and] sexually harass against their female colleagues” (Facebook.com/kazhigulova, November 9, 2023).

The normalization of violence against women within a culture often fuels societal unrest. (For how the war in Ukraine is influencing the normalization of violence in Russian society, see EDM, February 29.) Acceptance of domestic violence as part of life works in tandem with a heightened acceptance of societal violence in general. In Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, researchers have found a correlation between young people who experience domestic violence and those that join gangs or criminal organizations (Saferworld, March 2019; International Alert, March 2021). Societal distrust in the government’s ability to punish offenders, connected to their distrust in the efficacy of law enforcement, also leads to attempts to punish offenders through acts of “vigilante justice” (Marat, Policing Public Protest in Central Asia, 2014; Central Asian Analytical Network, March 2, 2021; Central Asia Program, April 23, 2021). In a society where domestic violence goes unchecked, taking the law into one’s own hands becomes a popular solution—exacerbating the overall levels of violence.

Domestic violence flourishes in societies with high levels of corruption, impunity, bureaucracy, and nepotism, all of which are present in Central Asian governments (Central Asia Program, April 23, 2021). Initiatives to tackle the issue across Central Asia—both governmental and non-governmental—have increased in recent years. For example, the Organization for Security Co-operation in Europe’s (OSCE) Regional Networking and Capacity Building Conference in Almaty in May provided a platform for advocacy groups and facilitated discussions about women’s rights and domestic violence in Central Asia (OSCE, May 29). The calls for reform following Nukenova’s death have led to some legislative changes, with more hopefully on the way in transforming societal norms and values. Increased collaboration between the Central Asian states in their fight against domestic violence will likely lead to further partnership in the region and a reframing of how each population perceives and responds to cases of domestic violence.