An Assessment of the Audit of Volkswagen’s Controversial Factory in Xinjiang

Publication: China Brief Volume: 24 Issue: 18

By:

Executive Summary:

- A recently leaked copy of the audit of Volkswagen’s much-criticized joint-venture factory in Xinjiang indicates that claims made by Volkswagen inside the report are misleading or false. These include suggestions that the audit applied the SA8000 social accountability standard, followed International Labor Organization standards, and was conducted by a firm with experience carrying out social audits.

- The audit shows that the factory organizes staff activities promoting “harmony” of all ethnic groups. Such activities are associated with forced assimilation, which raises severe ethical concerns over Volkswagen’s continued presence in the region.

- Liangma Law, a Shenzhen firm with ties to the Chinese Communist Party contracted for the audit, possesses no discernable experience in conducting social audits and does not advertise related services. Clive Greenwood, who joined Liangma shortly before the audit to participate in it, has publicly stated that SA8000 audits are worthless in the People’s Republic of China.

- Auditors did not ask general staff about forced labor. Interviews with Uyghur and other staff were remotely monitored via live video link, permitting direct state surveillance. Interviewees’ anonymity was not preserved. In short, SA8000 guidelines for worker interviews were grossly violated.

Editor’s Note: The screenshots of the Liangma Audit Report included in this article are strictly prohibited from being copied, reproduced, or distributed in any form without prior written consent.

A PDF version of this report can be read here. Readers are advised to view the PDF, as it contains higher resolution images of the Audit Report screenshots.

The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) operates the world’s largest contemporary system of forced labor, with up to 2.5 million ethnic persons at risk of coerced work through so-called “labor transfers,” a form of state-mandated work (Central Asian Survey, 2023; China Brief, February 14). This follows government policies that interned an estimated 1–2 million Uyghurs and other ethnic group members in re-education camps starting in 2017 (ChinaFile, 2022). In 2024, the International Labour Organization (ILO) updated its measurement guidelines, defining “labor transfer schemes” targeting ethnic minorities as a form of state-imposed forced labor (China Brief, April 14).

Since 2013, Germany’s Volkswagen Group has operated a joint venture factory in Urumqi, the region’s capital, together with Shanghai-based SAIC Motor Corporation (上汽集团). Following criticism over its continued presence in a region witnessing mass arbitrary detention and mass forced labor, in June 2023, Volkswagen promised an independent audit of the factory (Financial Times, June 21, 2023). The company did not publish the audit report, however. In a one-page statement published in December 2023, it claimed instead that the audit found “no indication of any human rights violations or wider issues around working conditions” (Volkswagen, December 5, 2023).

In August 2024, the advocacy organization Campaign for Uyghurs (CFU) received anonymous mail containing a copy of the full audit report prepared by the Chinese law firm Liangma Law (广东良马律师事务所) (Liangma, accessed August 20). Analysis of the audit report finds that:

- Volkswagen’s statements about the audit are misleading or false.

- Liangma’s claim that the audit “assessed compliance with the Social Accountability 8000 (SA8000) standard” is contradicted by the report itself.

- Publicly available information suggests that the persons in Liangma’s auditing team had no substantial prior expertise in conducting a social audit or an SA8000.

- The audit’s methodology and scope are unsuited to meaningfully assess the presence or absence of forced labor at the factory.

All entities and persons named in this report received a detailed list of questions about the audit, their roles in it, and their personal backgrounds. None replied except Volkswagen, which told me that it did not want to answer questions. In short, none of them chose to dispute the authenticity of the audit document or the veracity of key arguments made in this report. Shortly before publication of this report, Mr. Greenwood, the audit team’s most senior member, removed all references to Liangma from his LinkedIn profile and deleted his biography.

This report discusses Volkswagen’s presence in Xinjiang, reviews the authenticity of the leaked Liangma audit document, assesses Liangma’s connections to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), scrutinizes the identities and expertise of the individuals involved in the Liangma audit, and reviews the audit’s methodology, validity, and deviations from the SA8000 standard. It is supported by an expert assessment prepared for the author by Judy Gearhart, a professor at American University (AU), who also peer-reviewed this report (AU, accessed August 20). She served for twelve years as programs director at Social Accountability International (SAI), the entity behind the SA8000 standard, and was involved in developing the SA8000. Professor Gearhart points out that the standard itself was not designed to assess state-imposed forced labor. Experts have testified that factory audits are generally unable to identify this form of coerced work (see, e.g., CECC, April 30).

SAIC Volkswagen Joint Venture Linked to Coercive Labor Practices

The XUAR’s SAIC Volkswagen joint venture factory was established in 2013 (BBC, November 12, 2020). At the end of 2023, it employed 197 staff, 47 of them ethnic minorities (Associated Press, December 6, 2023). SAIC Volkswagen also operates a test track in the Uyghur region of Turpan. The track was built by the China Railway Engineering Corporation’s (CREC; 中国铁工) Fourth Bureau between 2015 and 2019 (CRGL, August 5, 2019). The track’s construction was overseen by the so-called Xinjiang Test Track Project (XTTP), a joint entity of SAIC Volkswagen and CREC.

Evidence from company and state media sources shows that the XTTP joined government work teams monitoring Uyghur families, arranging assimilatory “ethnic unity” activities, and facilitating the transfer of Uyghur surplus laborers as part of the well-known forced labor program (CREC, May 21, 2018; CREC Unions, March 9, 2017). CREC reports openly state that the project itself employed transferred Uyghur surplus laborers during the peak of the mass internments in 2017 and 2018 (CTCE, September 19, 2018; CREC, May 10, 2017). PRC media websites published photos showing Uyghur laborers employed by the project in military drill uniforms (the state uses military drilling to boost the discipline and obedience of transferred Uyghur workers) (CREC, December 25, 2018). In May 2017, right when the mass internments started, the XTTP drastically intensified the surveillance and supervision of employees (CREC, May 10, 2017). The project collected iris scans of employees and passed their information to the security services.

In sum, Volkswagen’s presence in Xinjiang is linked to well-documented coercive labor practices, and at least indirectly connected to activities related to surveillance, mass internment, and assimilation (Central Asian Survey, 2023).

The Liangma Law Audit Report

On August 2, the CFU office in Washington, D.C. received an anonymous package containing a copy of the Liangma Law audit report of the SAIC Volkswagen factory in Urumqi. The report was mailed from an unknown address in Germany. CFU then forwarded the report to the author. CFU contacted an entity that was able to confirm that the document sent to CFU was indeed the original audit report that Liangma had prepared for Volkswagen in late 2023.

The audit was conducted by three persons affiliated with Liangma Law whose identities can be independently corroborated: Mr. Simon Choi (蔡汉强), general counsel at Liangma and a lawyer who has held lectureships at different PRC universities; Ms. Wen (Jessica) Xu (徐雯), a corporate law partner and former PRC government employee; and Liangma’s Mr. Clive Greenwood, whose background is discussed

Figure 2: Cover page of the leaked Liangma audit report. (Source: Liangma Audit Report)

In March 2024, Ms. Xu posted an article on Liangma Law’s Weixin social media website. The bottom of the article features her portrait, which is identical to that posted on the Liangma Law website, and her biography. There, Ms. Xu boasts: “Recently, [Ms. Xu] provided an SA8000 social responsibility audit of the highest international standard for the domestic [i.e., PRC-based] automobile factory of a well-known German car company” (Weixin, March 20). This wording evidently refers to the November 2023 audit of the SAIC Volkswagen factory in Urumqi. Moreover, on a local Shenzhen website, Liangma states that Volkswagen has been among its clients (Now Shenzhen, August 1).

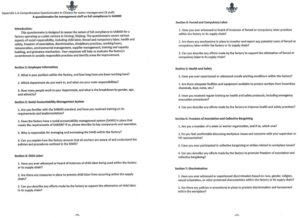

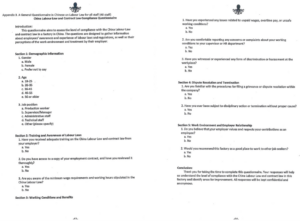

The Liangma audit report is marked “private and confidential.” It is dated November 20, 2023, about two weeks before Volkswagen announced the audit’s results on December 5. The report contains 37 A4-sized sheets displaying 71 numbered pages containing the main report (p.1–38), three appendices with the full staff questionnaires in English, Chinese, and Uyghur (p.39–69), two illustrations of the SAIC VW shareholder structure and overview of the Xinjiang factory (p.70), and a legal disclaimer (p.71). Page numbers are partially clipped, suggesting that it is a copy or printed scan of the original report.

The report contains 13 color photographs depicting an office with the factory’s name and logo, employee canteens, kiosks, entertainment facilities, factory halls, trilingual factory signs (in English, Chinese, and Uyghur), notice boards related to union and promotional activities for employees, and settings related to health and safety. Given that such images are not publicly available supports the report’s claim that they were taken by the factory photographer on behalf of the Liangma team (p.20).

The authenticity of the report is further corroborated by its similarity to other Liangma documents. Edgar Choi, head of the law firm’s International Department, operates a YouTube channel advertising Liangma’s services. In one video from February 2024, Choi interacts with a client over a Liangma-issued document (YouTube/Law In A Minute, February 8). A comparison with the audit report shows nearly identical page layouts, featuring the Liangma horse logo on the top-left and as a watermark in page centers (in the audit, this excluded the pages showing interview and survey questions).

The audit report itself suffers from numerous grammatical errors and awkward wording, suggesting that it was written by Liangma’s Chinese staff. It also uses three different ways to spell the word “Uyghur” (Uyghur, Uighur, and Uygur). The apparent lack of copy-editing suggests a lack of professionalism and expertise in this area, something that accords with other evidence concerning the practitioners who created the report, as detailed below. The report also contains a strongly worded legal disclaimer that notes that the information contained in the audit should “not [be] relied on” for “any purpose” and should not be “relied upon as professional advice.”

Figure 4: Images of a page of the Liangma audit (top-left) and screenshots from a promotional YouTube video posted by Liangma’s Edgar Choi. (Source: YouTube/Law In A Minute)

Volkswagen, Löning, and Their Presentation of the Liangma Audit

The Liangma audit report suggests that Volkswagen’s presentation of how the audit was performed was highly misleading.

In December 2023, Volkswagen stated that it had contracted the Berlin-based consultancy Löning – Human Rights & Responsible Business to “perform an ESG audit” of its Urumqi factory (Volkswagen, December 5, 2023). Löning was founded by Markus Löning, a former member of the German parliament who also served as Germany’s human rights commissioner between 2010 and 2013 (Löning, accessed August 12). The Volkswagen statement noted that “the actual audit execution was undertaken by a Shenzhen law firm … accompanied on site by Löning.” In an unsigned statement published by Volkswagen, Markus Löning asserted (Volkswagen, December 5, 2023):

We checked the employment contracts and salary payments of all 197 employees over the last three years, conducted 40 interviews, and were able to freely inspect the factory.

Löning later clarified that only one of its staff, Mr. Christian Ewert, was present on site during the audit, and that “no other team member from Löning participated in, supported, or backed this project” (LinkedIn/Löning, December, 2023). Mr. Ewert had joined Löning in June 2023, just months before the audit (LinkedIn/Löning, June 21, 2023). He previously served on the board of SAI, although it is not clear from publicly available information whether he ever directly oversaw the implementation of an SA8000 audit (SAI, July 2015). Curiously, Ewert’s expertise is not mentioned, either by the statements from Volkswagen and Löning or by the Liangma audit.

The Liangma report makes no mention of Löning or Mr. Ewert. Its numerous shortcomings make it doubtful whether Löning influenced the audit’s methodology, shaped its strategy, or suggested any corrections or improvements. In his quotes published by Volkswagen, Markus Löning claimed that “we … conducted 40 interviews” (Volkswagen, December 5, 2023). The Liangma report, however, gives no indication that Mr. Ewert actively participated in any part of the audit. The term “accompanied” used in Volkswagen’s statement suggests a passive role. Given that the report does not even mention Mr. Ewert’s presence and that Löning’s involvement neither addressed methodological gaps nor attempted to correct the report’s glaring linguistic errors, Volkswagen’s claim that Löning “performed” the audit is misleading.

Neither Mr. Ewert nor Löning responded to detailed questions about their role in the audit.

Immediately after the audit, several senior Löning employees publicly disavowed the audit exercise amid a reported “outrage” among staff (Financial Times, December 13, 2023). A comparison of Löning’s team page between December 2023 and August 2024 and related LinkedIn profiles suggests that 10 of 24 staff members have since left the firm, including Mr. Ewert (Löning, December 5, 2023, August 3).

Liangma Law’s Connections to the Chinese Communist Party

Liangma Law has significant ties to the CCP. This fact alone indicates that Uyghurs and other staff at the SAIC Volkswagen factory in Urumqi could not have conveyed sensitive information to the audit team without fearing repercussions.

All law firms in Shenzhen, where Liangma is based, are required by government decree to engage in CCP party-building activities (Shenzhen Lawyers Association [SLA], January 8, 2019). According to records published by the Shenzhen Lawyers Association, multiple Liangma staff members, including leading staff, are members of the CCP or affiliate entities. This includes Ms. Xu, a member of the audit team who also previously worked for a PRC government entity, and Li Liang (李良), Liangma’s director and founding partner (SLA, accessed August 20 [1] [2]).

Liangma has hosted several CCP events. In November 2023, just after the audit exercise, the firm hosted a meeting with the CCP Committee of the Shenzhen Lawyer Profession (SLA, November 17, 2023). At the event, Du Peng (杜朋), the secretary of Liangma’s CCP Party Branch, was joined by director Li. In 2020, Du Peng received the CCP Committee of the Shenzhen Lawyer Profession’s “Outstanding Communist Party Member Award” (Liangma Law, accessed August 20).

In July 2024, Liangma celebrated the CCP’s 103rd anniversary, during which employees sang the same patriotic song that Uyghurs detained for re-education have been forced to sing (Weixin/Liangma Law Office, July 2):

On the occasion of the “July 1” Founding Day of the Party, all Liangma Law party members sang the song “Without the Communist Party, There Would Be No New China,” expressing their deep affection for the Party and praising the happy life brought by reform and opening up.

The presence of the Party within Liangma Law suggests that any sensitive information could all too easily be shared with the PRC government. As explained in a separate section, Liangma auditors livestreamed interview sessions back to the firm’s head office. This would further enable surveillance of the interviewees, reducing the prospects that they would provide uninhibited responses to the auditors’ questions.

Figure 6: Liangma Law celebrates the CCP’s 103rd anniversary. (Source: Weixin/Liangma Law Office)

Liangma and Its Auditors’ Lack of Social Audit Expertise

Liangma

Volkswagen claimed that the audit was undertaken by “a Shenzhen law firm with extensive experience in social audits and international and Chinese labor law” (Volkswagen, December 5, 2023). However, while Liangma Law appears knowledgeable about PRC labor law, its online presence fails to substantiate Volkswagen’s claim about its experience conducting social audits.

The company website presents a wide range of business-related legal services, including corporate compliance, as well as legal services related to PRC labor law. A detailed search on Liangma’s website shows that the firm itself does not advertise auditing services, nor does it claim to have any expertise in conducting them. The author searched for evidence related to: [1]

- Social audits (社会审计).

- Services related to ESG (environment, social, and government; 环境、社会和治理审计) or CSR (corporate social responsibility; 社会责任审计).

- “Company audits (企业审计 or 公司审计).”

- “SA8000.”

- “Audit (审计).”

- “Social responsibility (社会责任).”

- “Labor standard (劳动标准).”

Liangma is not accredited by SAI to conduct certified SA8000 audits (see SAI, accessed August 20). On November 28, 2023, eight days after the preparation of the audit report, Liangma’s Edgar Choi posted on his personal LinkedIn that Liangma performs SA8000 audits, but Liangma itself does not advertise this service (LinkedIn/Edgar Choi, November 28, 2023). Liangma did not respond to questions about its auditing expertise or services.

Simon Choi and Wen Xu

Only two of the three auditors listed, Mr. Choi and Ms. Xu, signed the report. Their professional background and expertise are listed on the Liangma Law website and another site, Choi & Partners, run by Mr. Choi (See Liangma Law, accessed August 12; Liangma Law, accessed August 5; Choi & Partners, accessed August 20; Choi & Partners, accessed August 20). Choi & Partners and Liangma (established 1997 and 2016, respectively) are overlapping entities. Their office addresses and most staff are identical, and a staff photo on Choi & Partners’ “About” page shows the Liangma logo in the background (Choi & Partners, accessed August 20). Their websites do not mention each other.

Details about the evolution and nature of Choi & Partners are almost impossible to corroborate independently. The entity operates a relatively new website, first indexed by Google in February 2024. Searches for Choi & Partners with related keywords yield almost no results. The entity has no discernible social media presence besides a single YouTube video posted by “dana doors,” an anonymous account created in December 2023 (YouTube/dana doors, April 25).

Neither Mr. Choi nor Ms. Xu is described as holding any expertise in social audits, corporate audits, ESG, or SA8000, and neither is listed on either website as offering services related to these fields. In frequent LinkedIn posts between March 2017 and November 2021 that also advertised events where he spoke, Mr. Choi presented himself as knowledgeable in financial technology and PRC data security laws, besides holding legal and managerial expertise (LinkedIn/Simon Choi, November 18, 2021). None of these posts or events suggested direct engagement with corporate audits or SA8000.

Clive Greenwood

The website of Choi & Partners advertises social accountability compliance services, including SA8000 audits (Choi & Partners, August 8). However, the firm’s only team member shown as possessing any potential sustained expertise in company audits or supply chain due diligence is Clive Greenwood. Notably, Mr. Greenwood did not join Liangma until September 2023, immediately before the audit was conducted (LinkedIn/Clive Jameson-Greenwood, accessed August 20).

Mr. Greenwood’s enigmatic and in parts highly obscure background is marked by twists, turns, contradictions, and obfuscation. Some entities he claims to have founded or worked for have no active or discernible online or social media presence, and several appear to have either failed or fallen into obscurity. Mr. Greenwood did not respond to a detailed list of questions about his professional background, his role in the audit, and his apparent lack of expertise in conducting social audits.

Figure 8: Social media images of Clive Greenwood’s pub, The Drunken Chef. (Source: Facebook/clive.greenwood.7)

According to information posted online, Mr. Greenwood is a British Army veteran who moved to the PRC in 1989. Between 2004 and 2016, he ran a British sports pub in Suzhou called The Drunken Chef (see Facebook/The Drunken Chef, accessed September 16; LinkedIn/Clive Greenwood, accessed September 16; LinkedIn/clive greenwood, accessed September 16). According to a local report, Mr. Greenwood spent over 16 years in sales and marketing in the PRC before starting the pub (Suzhou Living, September 12, 2012). His first LinkedIn profile states that between 2003 and 2006, he worked as the Asia Sales and Marketing Manager for Northrop Grumman (LinkedIn/Clive Greenwood, accessed August 20). In 2013, he became general manager of Neurostim Systems, a company marketing medical services that was dissolved only two years later (LinkedIn/Clive Greenwood, accessed September 16; Companies House/NEUROSTIM SYSTEMS LIMITED, accessed September 16; Rocket Reach/Clive Greenwood, accessed September 16).

Mr. Greenwood’s workplaces between 2016, when his pub closed, and 2020 cannot be readily assessed from publicly available sources. In late 2021, he sought to rebrand himself and created a third LinkedIn profile that mentions neither his prior role at the sports pub nor the failed company. In April 2022, Mr. Greenwood advertised legal consulting, project management, and sourcing compliance services on LinkedIn without any other professional affiliation (LinkedIn/Clive Jameson-Greenwood, April 29, 2022).

Mr. Greenwood’s new LinkedIn profile lists his work experience as starting in 2020 as the founder of SMC GLOBAL Manufacturing Consultants. However, he did not publicly mention this entity until 2022 (LinkedIn/ Clive Jameson-Greenwood, April 30, 2022). The 2020 founding year is the likely basis for claims on his profile at Choi & Partners that Greenwood “spent the past 4 years advising a number of companies on compliance to ISO 13485, SA8000, EU MDR, and FDA 21 CFR 820” (Choi & Partner, July 25). With the exception of SA8000, these standards pertain to quality control and management, not social auditing or forced labor risk assessments.

The implied claim that Mr. Greenwood has four years of experience with SA8000 audits is most likely misleading. Mr. Greenwood’s LinkedIn feed showed the first signs of an active public engagement with ESG and social accountability standards around mid-2023. On November 9, only 6 days after the audit exercise was concluded on November 3, Mr. Greenwood advertised services related to SA8000 for the first time (LinkedIn/Clive Jameson-Greenwood, November 9, 2023). The SA8000 standard is not mentioned on SMC GLOBAL’s website, nor on Mr. Greenwood’s now-deleted biography or earlier LinkedIn profile.

SMC GLOBAL’s website features a decidedly unprofessional layout and textual presentation, and only Mr. Greenwood’s first name appears on it (SMC Compliance, accessed August 12). Most of the website’s navigation buttons do not work and basic spelling errors are ubiquitous. The website does not appear to have been updated since 2022. On it, Mr. Greenwood advertises compliance risk assessments, quality assurance management, and legal representation for disputes with PRC-based suppliers.

According to his LinkedIn posts, Mr. Greenwood joined Liangma Law around October 10, 2023, less than four weeks before the Urumqi factory audit took place (LinkedIn, October 10, 2023). His current (and third) LinkedIn page lists him as Senior Compliance Counsel at Guangdong Liangma Law. However, he is not shown anywhere on Liangma’s website. Instead, he is featured as a team member on Choi & Partners’ website, albeit with a different title, Chief Compliance Officer, which is also used in the audit report (Choi & Partners, accessed August 20). On a local website, Liangma advertises its services with a digitally-manipulated staff image from Choi & Partners, where Simon Choi’s depiction is replaced with that of Clive Greenwood (Now Shenzhen, August 1).

The Choi & Partners website states that Mr. Greenwood possesses in-depth global manufacturing and quality & compliance experience (Choi & Partners, July 25). It provides a highly selective portrayal of his eclectic background. There is no publicly available information to suggest that prior to joining Liangma, Mr. Greenwood ever conducted an SA8000 audit, an ESG assessment, or a social audit with a focus on assessing forced labor risks.

Mr. Greenwood’s page on Choi & Partners makes the demonstrably false claim that he was cited by the BBC, CNBC, and the New York Times. Mr. Greenwood was cited in the South China Morning Post as the “director” of Wilson, Woodman & Greenwood Associates—another obscure entity linked to him with no discernible online presence (SCMP, April 17, 2020). An article in The Telegraph describes him as a “British consultant in China” (The Telegraph, April 18, 2020). In both pieces, Mr. Greenwood is said to be occupied with yet another potentially short-lived engagement—shipping medical equipment during the early COVID outbreak.

It is doubtful whether Mr. Greenwood considers SA8000 audits in the PRC to be an effective tool for addressing forced labor risks. Only weeks before joining the Urumqi factory audit, on September 28, 2023, he made a disparaging post on LinkedIn, indicating with a photo of a pile of peanuts that the value of an SA8000 audit in the PRC is essentially worthless (LinkedIn/Clive Jameson-Greenwood, September 28, 2023; see Figure 1). On April 19, 2023, Greenwood indicated that he was fully aware of the risks related to Uyghur forced labor and of the difficulties conducting meaningful due diligence (LinkedIn/Clive Jameson-Greenwood, April 19, 2023):

Risk Assessment, buying from China and the UFLPA [Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act] … The Strategy indicates that, to conduct a forced labor risk assessment, importers must map supply chains for their imported goods and then identify steps at risk of using forced labor …

To conduct a meaningful and accurate Due Diligence or a [Forced Labor] Risk Assessment, one thing becomes clear, transparency, in China the supply chain is muddy at best, simply getting to the information is festooned with danger, diversions, and road blocks, the question must be asked which is, is it actually worth the trouble.

Mr. Greenwood did not sign the audit report and clearly did not copy-edit its contents. It is uncertain whether he played any role in writing or reviewing the final report. It is even less certain whether he believes that this audit possesses any validity.

In short, it appears that Volkswagen, one of the world’s largest corporations, chose for its high-stakes audit a largely unknown PRC law firm with a foreign-facing shell-like counterpart, along with an equally unknown Western expert. Both are without demonstrated and sustained prior expertise in SA8000 or social audits focused on assessing forced labor risks. The resulting effort was then billed as an audit performed by Löning, presumably to make it more palatable for a German audience.

Assessing the Liangma Audit’s Methodology [2]

Compliance with the SA8000 standard

In its introduction, the Liangma audit claims that it “assessed compliance with the SA8000 standard” (p.1). However, on page 19, the report concedes that contrary to what the auditors had expected, the factory did not follow SA8000:

Upon perusal, checking the documents available and verifications with the management, it was confirmed that SA8000 was not the standard practised in the factory; however, with further perusal of other policies, it was confirmed that there was another set of standards corresponding with SA8000 was in place. […] For the fact that the time limitation of the audit did not allow the auditors to revise the requested document list to accommodate such an unexpected issue, the auditor by and large, opines that SA8000 principles were realised and observed in this audit exercise.

In short, communication between SAIC Volkswagen and Liangma was so inadequate that the auditors were incorrectly expecting to audit an entity that was actively following the SA8000 standard. This contrasts sharply with the fact that SA8000 audits require self-assessments before inspection visits (SAI, May 2016, p.95). Unable to review all SA8000-required documentation, the auditing team thus merely “opines” that the audit followed SA8000 in principle. However, the audit fails to provide a detailed comparison of the factory’s allegedly “corresponding” standard with SA8000.

Even the claim that the audit followed SA8000 “in principle” cannot be upheld. The audit failed to assess the compliance of the factory’s suppliers, sub-suppliers, and private employment agencies with the SA8000, a required component of SA8000 audits (SAI, May 2016, section 9.10.1). The audit claims to have found no evidence of active discrimination, but the SA8000 guidance requires an evaluation of passive organizational practices that may result in discrimination based on a lack of affirmative action (SAI, May 2016, p.60). The audit’s surveys and interviews omitted sensitive aspects in mandatory SA8000 evaluation categories, such as discrimination for holding “political opinions” (SAI, May 2016, sections 5.1, 5.2).

The audit assessed visible evidence of coerced work, reviewed related company policies and staff contracts for compliance with PRC labor laws, and asked management staff whether they had witnessed coercion, knew of mechanisms to report related incidents, and knew how the factory was working to eliminate forced labor in its supply chain (p.24–5). Notably, the recorded responses entirely omit the question of forced labor in supply chains, suggesting that the interviewees were not comfortable responding to more sensitive questions. The questionnaires for general staff did not contain any direct questions about forced labor risks. The only questions related to forced labor were closed-ended questions about fair compensation and work hours. Professor Gearhart concurs that the audit’s review of forced labor “is very poor,” noting, among other issues, a lack of corresponding answers by management staff to several of the auditors’ forced labor questions (p.24–25).

The audit also omitted multiple additional required evaluation categories listed in SA8000 documentation for forced labor. Per SA8000 Section IV (2), the audit must also evaluate whether:

- Workers are freely able to terminate the work relationship.

- Identity documents are being withheld.

- Workers are forced to bear employment fees or costs.

- The workplace or the entities supplying the labor engage in or support human trafficking.

The SA8000 Performance Indicator Annex and Guidance documents stipulate that audits also must assess whether:

- There are unreasonable restraints on personnel’s freedom of movement.

- Workers have access to religious facilities.

- Security measures implemented by the organization do not intimidate or unduly restrict the movement of workers.

- The potential involvement of intermediary private or state-run employment agencies and their recruitment practices results in ethical or forced labor risks.

The Liangma audit failed to investigate any of these eight aspects. [3] It did not examine how workers entered their work, whether they were sent to the factory through a state-led work program, or whether they could leave work without fearing repercussions. It also failed to assess indicators related to free movement, such as workers’ ability to leave the factory or return home. The audit’s lack of an assessment of contextual forced labor factors and its failure to conduct the supply chain due diligence required by the SA8000 standard impacts its validity.

Compliance with ILO standards

The audit also made no valid attempt to assess full compliance with ILO standards. The widely used set of 11 indicators published by the ILO for on-site inspections was not applied. Neither management nor worker questionnaires were designed to assess the two dimensions of the ILO’s definition of forced labor: (1) work entered without free and informed consent; (2) the menace of a penalty (coercion) related to entering work, during work, or related to leaving work (ILO, accessed August 20). Contrary to its claim that it “considered” compliance with ILO Convention 105, the audit did not assess the five dimensions of state-imposed labor outlined in that convention (ILO, 1957).

Volkswagen and Löning’s claims that the Urumqi factory complies with ILO standards must therefore be considered unproven. Moreover, the audit inadvertently uncovered that, like all other companies in Xinjiang, the SAIC Volkswagen factory promotes ethnic unity activities among ethnic groups to ensure that they are “in harmony” with each other (p.27; Figure 13). This practice is in line with XUAR government mandates. It raises significant concerns over Volkswagen’s continued presence in the region, given that its factory aids the state in enforcing its ethnic policies.

Staff Interviews and Surveys

According to the audit report, the three auditors “randomly” selected 40 of the factory’s 197 staff for interviews. These comprised eight management staff and 32 general staff (p.21–22). Two of the eight management staff (25 percent) and seven of the 32 general staff members (22 percent) selected for the interviews were non-Han. Their precise ethnic designation is not disclosed. A licensed Uyghur translator was available on request, but the audit does not say who appointed this translator.

All interviewees were first subjected to a group briefing in an open space within the factory, an unfortunate decision that ensured that their identities did not remain anonymous. There was no attempt to interview workers off-site for increased confidentiality and anonymity.

The explanation of the interview process contains some decidedly strange language (pp.21–23):

The interviewing table (see below photo) was set to a triangular shape with comfortable seat on each side of the table. Interviewees were not 180 seating opposite to the auditor. Interviewee eyes were not facing sunshine from the windows … Interview table was set in triangular shaped and there was no direct confrontation between the interviewee and interviewer psychologically. Also, there was a team of senior associates at back office in Liangma Shenzhen office to assist and analyze the interview with livestream.

The interview sessions involved a livestream connection to Liangma’s head office. All PRC citizens know that the state has full control over digitally transmitted data. This alone would have compromised confidentiality. In addition, Uyghurs are aware that the state uses Han Chinese citizens to spy on them, most notably in the form of village-based work teams (Central Asian Survey, 2023). The presence of Han Chinese lawyers alone would have been sufficient to prevent Uyghur and other ethnic staff from providing responses that could draw the attention of the state and potentially lead to their detention for re-education.

The primary texts of the questionnaires are well-written, and do not contain the linguistic inaccuracies found throughout the rest of the report. The questionnaires conclude by thanking participants for “taking the time to complete this questionnaire.” However, the report suggests that the interactions occurred individually with each informant in an interview setting and, therefore, most likely through verbal communication (such as auditors reading out questions and recording interviewee verbal responses). Liangma prepared questions in English and Chinese and commissioned a Uyghur translation. The English and Chinese versions are consistent. The author’s Uyghur research assistant only detected relatively minor and likely inadvertent errors in the Uyghur translation.

Auditors’ interactions with management staff differed from their interactions with regular staff. While they used open-ended questions with the former group, only closed-ended questions were used with the latter. This prevented workers from speaking freely and at length about their situation. Predictably, survey result summaries reflect highly superficial and homogenous responses. In most instances, all or nearly all interviewees responded that everything was fine. Where responses deviated slightly, no ethnic breakdown was provided. Additionally, no effort was made to shed light on contextual factors essential for forced labor risk assessments, such as how staff ended up applying for jobs at the factory, if there were any intermediaries or state agencies involved, and if staff were influenced by official policies in their choice of employment.

Liangma’s approach completely ignored SA8000 Guidance for worker interviews, which explicitly mandates a comprehensive focus on broader contextual factors behind forced labor risks (SA8000 Guidance, May, 2016):

As mentioned in other areas of the Guidance, many organisations not directly using forced labour might still support the use of it in other ways, such as hiring temporary workers through subcontractors to work on their premises, contracting out their production, imposing overtime work upon workers without seeking their consent, or limiting workers’ freedom of movement after work. The purpose of conducting interviews with workers therefore is not only to learn if there is forced labour on a particular worksite at a particular time, but also to determine whether any labour practice at the facility is non-voluntary by nature …

Before visiting the facility, it is highly recommended that auditors consult extensively with local trade unions, NGOs, and community groups … If forced or any form of compulsory labour is a concern, auditors should prioritize this issue when planning the interviews with workers.

There is a possibility that the Liangma audit was designed to avoid endangering ethnic staff by preventing them from giving responses that could lead to repercussions. In doing so, however, it eliminated any potential for meaningfully assessing forced labor risks. This is consistent with Markus Löning’s admission to the Financial Times that the main basis for the audit was a review of documentation rather than interviews because, he said, “[e]ven if [staff] would be aware of something, they cannot say that in an interview” (Financial Times, December 13, 2023).

Conclusion

Volkswagen used an inexperienced and little-known PRC law firm and a highly obscure Western expert not experienced in social audits or SA8000 to perform a high-stakes audit of its much-criticized joint venture factory in Urumqi. Volkswagen then proceeded to conceal Liangma and Mr. Greenwood’s obscure identities, instead foregrounding Löning, a German entity, likely to make it more presentable to a German audience.

Liangma’s audit did not conform to the SA8000 standard that it claimed to assess. Shortcomings in the audit’s method and implementation mean that it was not able to adequately assess forced labor risks.

Several claims made by Volkswagen about the audit are misleading or false (see Table 1 below). As a result, investors and index providers such as MSCI should avoid including Volkswagen’s stock in their ESG portfolios.

| Volkswagen’s Claims Regarding the Audit | Assessment of Each Claim |

| “Due to the audit scope, Loening has decided to apply the internationally renowned Audit Standard SA8000.” | Misleading or false. Liangma sought to assess SA8000, but no such assessment was ultimately conducted since there was “no time” to adjust the required documentation list. Prof. Gearhart confirms that the Liangma audit fails to conform to SA8000. |

| “Loening – Human Rights & Responsible Business GmbH has been contracted by Volkswagen to perform an ESG Audit on the aforementioned legal entity” | The term “perform” is misleading. The audit report does not mention Löning’s presence, and Löning’s alleged involvement appears to have neither addressed the audit’s methodological gaps nor attempted to correct the report’s errors. |

| “The actual audit execution was undertaken by a Shenzhen law firm with extensive experience in social audits … and accompanied on site by Loening.” | Misleading or false. Neither Liangma nor Clive Greenwood appear to have had any sustained experience with social audits or the SA8000 prior to November 2023. The fact that Löning accompanied Liangma on site is not corroborated by the audit report. |

| The audit included “interviews with staff and management employees of the audited legal entity.” | Misleading. General staff were only asked highly decontextualized, closed-ended questions in survey form, in violation of SA8000 guidance on worker interviews. |

| “No violations of ILO Conventions C029, C111 or C155 could be detected as a result of the audit … In sum, the labor practices were in compliance with Chinese law and the standards of the ILO Conventions that the People’s Republic of China has ratified.” | Misleading or false. The audit was not designed to assess forced labor as defined by the ILO. The ILO’s widely used 11 indicators were not fully employed. The audit ignored multiple indicators and categories related to forced labor assessment required by SA8000. It did not assess ILO Convention 105 on state-imposed forced labor that the PRC ratified. |

Table 1: Assessment of Volkswagen’s Claims Regarding the Audit. (Source: Volkswagen, December 5, 2023)

Notes

[1] For reference to PRC audit-related terminology, see for example www.audit.gov.cn and www.finlaw.pku.edu.

[2] In addition to the author’s own analysis, this section draws on an expert assessment prepared for the author by Professor Gearhart.

[3] Auditors asked management staff whether there were difficulties or delays in receiving salaries or benefits, but this question was not put to all staff.