A Family Divided: The CCP’s Central Ethnic Work Conference

Publication: China Brief Volume: 14 Issue: 21

By:

For over a decade, academics and policymakers have been engaged in an unusually public and at times ad hominem debate over the future direction of China’s ethnic policies. [1] A group of maverick Chinese thinkers claim current policies engender disunity and could cause China to implode along its ethnic seams. Many others contend China’s diversity is its greatest strength and call for new legal provisions aimed at protecting ethnic cultures, autonomy and identities. The stakes have increased markedly since Chinese President Xi Jinping took power in November 2013, with hundreds of violent incidents revealing obvious fault-lines in ethnic relations across the country.

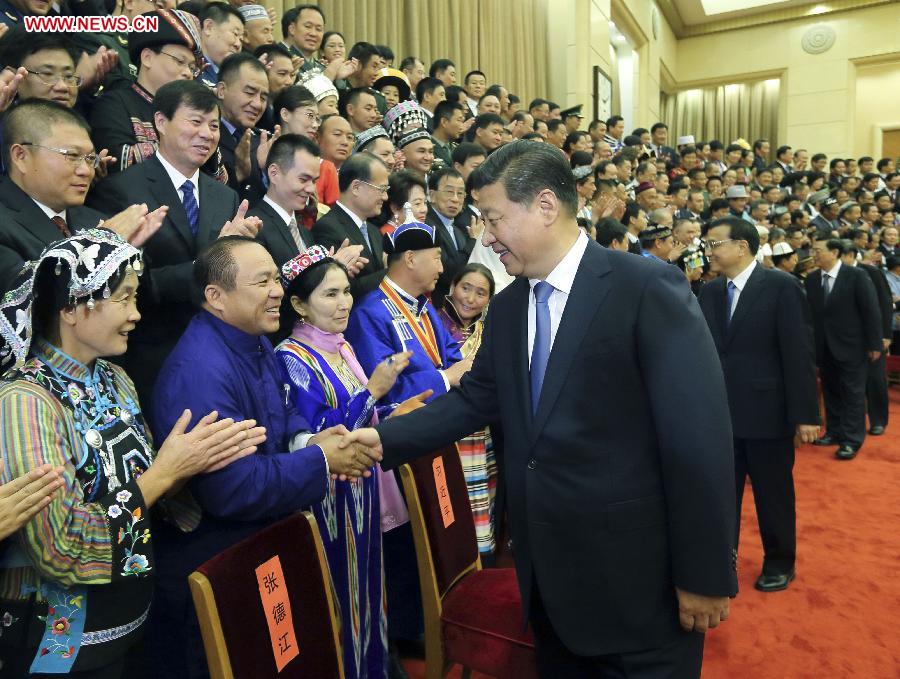

The recently convened Central Ethnic Work Conference sought to resolve this disagreement: “to unite thinking, clarify tasks and objectives and steady confidence and resolve” (Xinhua, September 29). The two-day meeting was chaired by Xi Jinping and attended by the entire Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) (with the exception of Zhang Gaoli, who was overseas) and over a thousand other leaders in Beijing on September 28–29. The meeting received extensive coverage in the Chinese state-run media, including four front-page editorials in the People’s Daily, yet virtually no attention in the international media.

In his speech at the conference, Xi stressed the need to “resolutely walk the correct road of China’s unique solution to the ethnic question.” He spoke for the first time about adhering to the “eight persistences” (bage jianchi)—a typically awkward formulation that seeks to juggle contradictory positions within China’s ethnic policy community by placing minority autonomy side-by-side with safeguarding the unity of the motherland (Qiushi, October 13). [2] As such, the meeting produced some subtle rhetorical adjustments while failing to bridge the differences in opinion or pioneer any bold new direction in policy. In fact, both sides in the debate are already using Xi’s speech to advance their own positions.

Xi Put His Own Stamp on Ethnic Work

On the evening of September 29, the People’s Daily broke the news of this important gathering on its official Weixin social-media account with a post entitled: “Xi Jinping’s ‘Fresh Thinking’ on Ethnic Work” (NetEase, September 29). The report highlighted several “completely new angles” emerging from this Party confab; yet it incorrectly identified the meeting as the third Central Ethnic Work Conference, mentioning the two gatherings convened by former Chinese president Jiang Zemin in 1992 and 1999 but omitting the last conference held in 2005 under the leadership of Xi’s predecessor, former Chinese president Hu Jintao (Xinhua, May 27, 2005). [3]

The oversight appears to have been accidental, with subsequent reports including Hu’s conference. However, it does highlight Xi’s determination to put forward his own formula for achieving ethnic harmony. Like other policy areas, he has staked his personal authority on the management of this contentious and sensitive policy arena. In the face of the current spate of ethnic violence—which reached the political center in October 2012 when a gasoline-laden car exploded in front of the Forbidden City in Beijing—Xi wants to look strong and decisive on ethnic issues.

In his first two years in office, Xi Jinping has chaired no fewer than eight gatherings of the Politburo or PBSC on ethnic work, including this May’s Second Central Work Forum on Xinjiang (see China Brief, June 19), while also personally touring ethnic minority communities in Gansu (February 2013), western Hunan (November 2013), Inner Mongolia (January 2014) and Xinjiang (April 2014). The State Ethnic Affairs Commission (SEAC) has even created a special website to highlight Xi and other PBSC members’ activities on ethnic affairs (SEAC).

For all of the Party’s public emphasis on their efforts, none of Xi’s speeches on ethnic policy have been made public. The official Xinhua New Agency provides summaries of key meetings as well as select excerpts, leaving analysts to piece together a range of inconsistent and often divergent messages. Xinhua’s summary of the recent Central Ethnic Work Conference is a consensus document: one that pastes over deep divisions on how best to end the current cycle of violence and engender harmonious ethnic relations.

Carefully Walking the Chinese Road

In his speech, Xi Jinping stressed the need for patience and confidence with the current approach. Like previous pronouncements, the conference affirmed the “correctness” of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) ethnic theory and policies since 1949. “Ethnic relations in our country are generally harmonious,” Xi is quoted as saying, “and our country’s ethnic work has been successful” (Xinhua, September 29). Yet, the conference summary also speaks about the “distinctive features” of ethnic work in a “new stage.” On the one hand, the Party must “unflinchingly walk the correct road of China’s unique solution to the ethnic question,” yet also “pioneer new thinking” and “forge new methods.” This reflects the Party’s never-ending quest to adapt outdated policies to new conditions without abandoning outright their predecessors’ policies and pet-slogans.

Much of the ethnic policy debate has revolved around the most appropriate models for China. Critics of current policies, like Peking University sociologist Ma Rong and Tsinghua University economist Hu Angang, argue China’s Soviet-inspired policies possess all the preconditions for state disintegration (strong ethnic consciousness, ethnic homelands in the form of autonomous regions and ethnic leadership), thus creating the possibility that China will share the fate of the former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia.

These reformers call for the abandonment of the current “hors d’oeuvres-style” policies and the adoption of the “melting pot” model that has proven successful, in their eyes, in countries like the United States, India, Brazil and Singapore. They make it clear that they would like to see a “weakening” (danhua) of ethnic identity and the eventual elimination of ethnic-based preferences and the system of regional ethnic autonomy. Ma Rong recently referred to regional autonomy as “a viable option for a period of transition, but in the long run it has certain weaknesses” (Asian Ethnicity, January 9). And one of the Party’s top ethnic policy advisors, Zhu Weiqun, recently hinted there might come a day when the system outgrows its usefulness (Xinhua, July 28).

Yet, as recent events in Ferguson, Missouri, demonstrate, the melting pot has failed to eliminate ethnic problems in countries like United States, a point that Hao Shiyuan, the influential deputy secretary general of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), has long stressed in opposition to the reformers (Global Times, August 22, 2012). Hao and other members of the ethnic establishment are already talking up the fact that the system of regional ethnic autonomy was included amongst Xi’s eight persistencies (Xinhua, September 30; Xinhua, October 23).

According to the “guiding document” (ganglingxing wenxian) the SEAC issued for studying Xi’s conference speech, “Western countries have not developed any miraculous cure in their attempt to solve ethnic problems, and some developing countries have also failed to solve the ethnic problems after imitating the West” (Qiushi, October 16). The document paraphrases Xi as stating the system of regional ethnic autonomy exceeds not only the Soviet model of “national self-determination” but also previous Chinese approaches such as “the grand union” (dayitong) and “rule according to customs” (yinsu erzhi), and thus forms a fundamental part of the Party’s innovative and pioneering approach to ethnic contradictions.

The SEAC document, written by its director, Wang Zhengwei, admits a loss of confidence in the current approach among some Party members and differences of opinion. He refers to Xi’s speech as a “summary determination offering the final word” on this disagreement, and a “lofty judgment” aimed at “clearing up muddled thinking and providing a tranquilizer for the cadres and masses of each ethnic group so they can sturdy the foundation of ethnic unity and progress.” Wang flatly declares: “It’s time to stop suggesting that the system of ethnic autonomy should be abolished!” Rather, everyone should “consolidate their energies in order to carry out their work effectively” while “strengthening confidence in our own road” (Qiushi, October 16).

Yet, as another editorial in Qiushi noted after the meeting (Qiushi, October 13), Xi also spoke about the importance of the “two integrations” when it comes to “persisting and perfecting” the system of regional ethnic autonomy: the mutual link between autonomy and unity, as well as ethnic and regional factors. Here Xi seems to validate the concerns of those who argue regional autonomy and minority preferences hinder the free flow of capital, goods and people, thus undermining a single national market and shared national identity. Xi’s speech leaves open the possibility of a future restructuring of provincial-level administrative structures, as recommended in Hu Angang’s call for a “second generation of ethnic policies” (see China Brief, July 6, 2012). Some influential Party members have argued in the past, for example, that Xinjiang and Tibet should be divided in two in order to dilute ethnic influences and conflicts (Aisixiang, April 15, 2004).

In the Spirit of Unity

Unlike his immediate predecessors’ narrow focus on economic development for improving ethnic relations, Xi Jinping is harking back to Maoist and Republican times in emphasizing the “spiritual,” “political,” and “cultural” basis of interethnic harmony and national unity. “Cultural identity,” Xi is quoted as saying at the Central Ethnic Work Conference, “is the foundation and long-term basis for strengthening the great unity of the Chinese nation; we must build a shared spiritual homeland and energetically foster a shared consciousness of the Chinese nation” (Xinhua, October 9).

The conference affirmed the need to accelerate development in ethnic areas with a special focus on addressing livelihood issues such as employment and education. At the same time, Xi stressed that these “material” concerns need to be complemented with a new focus on “spiritual” issues. Some minority cadres interpret this as paying closer attention to the religious needs of ethnic minorities (Xinhua, October 23); yet, there is clear evidence that Xi Jinping shares the concerns of Ma Rong and others about the weak identification of some ethnic minorities toward the nation. National identity, Xi has often made clear, should always trump narrow religious and ethnic affiliations.

Since coming to power, Xi Jinping and other PBSC members have spoken repeatedly of the need to strengthen the “four identifications” (sige rentong)—identification with the motherland; the Chinese nation; Chinese culture; and the socialist road with Chinese characteristics—among the ethnic minorities. This theme again featured prominently at the conference and marks a significant departure from Hu Jintao’s approach to ethnic work. Economic development is no panacea for ethnic problems, CASS researcher Ma Dazheng told Xinhua. Rather, interethnic “mingling” (jiaorong) is also required to forge a collective sense of national belonging (Xinhua, October 23).

In fact, interethnic “contact, exchange and mingling” has emerged as the new “guiding principal” (tifa) for ethnic work under Xi Jinping. Recent Chinese media reports highlight efforts to boost interethnic marriage rates, build mix-residency communities, establish integrated schools and classrooms, as well as more diverse workplaces through export-labour schemes that lure Uyghurs and Tibetans to work alongside their Han compatriots in coastal cities (People’s Daily, September 2; Tianshan, September 14; Xinhua, September 15; Southern Daily, October 30).

China’s history, Xi argued in a 2011 speech on the importance of studying Chinese history, reveals a continual process of interethnic mingling and fusion in the pursuit of a “all-under-heaven grand harmony” (tianxia datong) (Phoenix, September 5, 2011). Zhu Weiqun, the Director of the CPPCC’s Ethnic and Religious Affairs Committee, recently quoted former Chinese premier Zhou Enlai as saying in 1957: “If assimilation is one ethnic group using force to destroy another ethnic group, this is reactionary; yet if assimilation is each ethnic group naturally fusing together in search of common prosperity, this is progress” (Xinhua, July 28). “Mingling is not Hanification,” a Xinhua editorial asserts, “as it does not negate minority history and culture” (Xinhua, September 16).

At the Central Ethnic Work Conference, the goal of ethnic blending was coupled with “respect for differences and tolerance of diversity,” revealing again this attempt to balance competing concerns. There is a growing realization that mingling might increase ethnic tensions and conflict, especially in cities, and thus the importance of “urban ethnic work” was accentuated, with the conference calling on city officials to adopt neither a “close-door mentality” nor a “laissez-faire attitude” toward the minority floating population (Xinhua, September 29).

All in the Family?

As elsewhere, the family is a frequent metaphor for the nation in China. “The relationship between the Chinese nation and each ethnic group is like that of a large family and its members,” Xi told the conference, “and relations between different ethnic groups is like those of different members of this large family.” While kinfolk might disagree or even fight from time-to-time, they share a common bond in history and blood, rendering them a “community of shared destiny” (mingyun gongtongti), according to a front-page editorial in the Party’s mouthpiece (People’s Daily, October 10). “Through the long revolutionary struggle and resistance to outside invasion, the blood of each ethnic group has come together and fused in bonds of life and death, flesh and blood, weal and woe, so they are now reflected in the collective belonging and identification of all ethnic groups with the Chinese nation” (Qiushi, July 31).

Yet like an internal family feud, the ethnic policy debate will continue in the wake of the Central Ethnic Work Conference, with both sides finding new ground to push forward their positions. Reformers will likely look for more concrete proposals to spur mingling and cultural fusion: the removal of administrative barriers and new initiatives aimed at increasing interethnic mobility, marriage, schooling and cohabitation. They will likely seek to use adjustments to the household registration system, legal and administrative reforms and the state’s ambitious urbanization plan as springboards for building national cohesion and weakening minority autonomy and identity.

At the same time, those inside the vast ethnic bureaucracy will continue to rally around the system of regional ethnic autonomy, which is a formidable obstacle to any attempt to implement a “second generation of ethnic policies.” Yet, they are unlikely to gain any ground on their call for the passage of more detailed regulations and rules for implementing and strengthening regional autonomy. In an article celebrating the 30th anniversary of the Law on Regional Ethnic Autonomy, Wang Zhengwei pointed out “the fundamental aim [of the system] is to achieve and safeguard state uniformity and national unity” (People’s Daily, September 3).

Both sides agree the “Chinese family” must remain united. And while they will continue to probe the effectiveness of current policies, few dare question the Party’s authority. As clan patriarch, the Party remains the final arbitrator of who and what can be said on behalf of the nation, as the recent silencing of moderate Uyghur academic Ilham Tohti forcefully reminds us. The “China Dream” is the collective dream of all Chinese people, Xi Jinping consistently stresses, meaning restive minorities and outspoken critics must ultimately yield before the motherland if China hopes to achieve the great revival of the Chinese nation and race by 2049.

Notes

- For an overview of this debate, see: Mark Elliott, “The case of the missing indigene: Debate over the ‘Second-Generation’ Ethnic Policy,” The China Journal 73 (January 2015): 1–28; Ma Rong, “Reflections on the debate on China’s ethnic policy: my reform proposal and their critics,” Asian Ethnicity (2014): 1–10; James Leibold, Ethnic policy in China: Is reform inevitable? (Honolulu: East West Center, 2013); Barry Sautman, “Paved with good intentions: Proposals to curb minority rights and their consequences for China,” Modern China 38:1 (2012): 10–39.

- The “eight persistences” (bage jianchi) are: the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party; China’s unique socialist road; safeguarding the unity of the motherland; the uniform equality of all ethnic groups; the perfection of the system of regional ethnic autonomy; striving for mutual unity and prosperity for all ethnic groups; forging an ideological basis for an integrated Chinese nation; and governing the country according to law.

- The message was deleted from the People’s Daily’s Weixin feed but remains on the Internet in the form of a September 29 article published by Pengpai News in Shanghai, which reproduced the entire Weixin message, and has subsequently been posted on several websites, including an information portal (Zhongguo minzu zongjiao wang) managed by the SEAC.