Al-Awlaki Recruits Bangladeshi Militants for Strike on the United States

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 7

By:

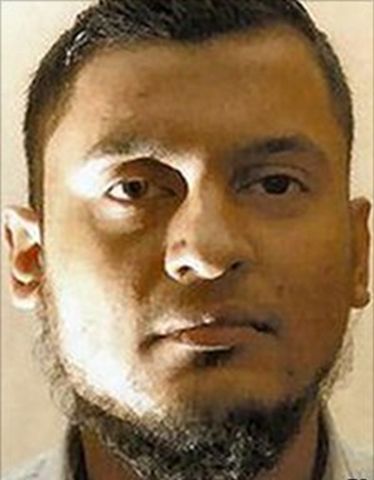

Rajib Karim, a 31-year-old Bangladeshi national resident in the United Kingdom, pled guilty on January 31 to charges of assisting Bangladeshi terrorist group Jamaat ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB). Confessing to helping produce and distribute videos on behalf of the JMB, sending money for terrorist purposes and offering himself for terror training abroad, Karim’s admission was made public at the beginning of a trial against him at Woolwich Crown Court in suburban London (Press Association [London], January 31; BdNews24.com [Dhaka], February 2).

Founded in 1998, the JMB is the largest extremist group in Bangladesh. The movement has expressed its opposition to democracy, socialism, secularism, cultural events, public entertainment and women’s rights through hundreds of bombings within Bangladesh. Though banned in 2005, the movement is believed to still maintain ties with various Islamist groups in the country.

On trial for further charges of preparing acts of terrorism in the UK, it has been suggested in the press that Karim was identified by the Home Secretary as a suspected agent for al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) (Press Association, November 3, 2010). [1]

According to information released at the opening of his trial, Karim first came to the UK in 2006 with his wife to seek a hospital for their child who was sick with what they thought was cancer (Guardian, February 2). The child got better and by September of the next year Karim had secured a position in a British Airways trainee scheme in Newcastle. According to the prosecution, he established himself as a sleeper agent in the UK, making “a very conscious and successful effort to adopt this low profile.” He kept his beard short, did not become involved in local Muslim groups, did not express radical views, played football locally, went to the gym and was described by people who knew him as “mild-mannered, well-educated and respectful” (Newcastle Evening Chronicle, February 2).

Much of the prosecution’s information on Karim appears to come from electronic communications between himself and his brother Tehzeeb that the police were able to find on Karim’s hard-drive. According to the prosecutor’s opening statement, Tehzeeb was also a long-term radical for JMB who travelled in 2009 with two others from Bangladesh to Yemen to seek out Anwar al-Awlaki (Press Association, February 1). Once connected with Awlaki, Tehzeeb told the Yemeni-American preacher of his brother. Awlaki recognized the benefits of having such a contact in place and in January 2010, the preacher is said to have emailed Karim, saying “my advice to you is to remain in your current position….I pray that Allah may grant us a breakthrough through you [to find] limitations and cracks in airport security systems.” The preacher apparently found the brothers of such importance that he sent them a personal voice message to counter claims of his death that had circulated in December 2009 (Press Association, February 2).

It seems as though Karim was in contact with extremist commanders long before this. According to the prosecution’s case, anonymous “terror chiefs abroad” wanted him to remain in his British Airways job as far back as November 2007 and to become a “managing director” for them. In an email exchange with his brother at around this time, the two discussed whether a small team could also “be the beginning of another July Seven;” a supposed reference to the July 7, 2005 terrorist attacks on London’s underground system (Press Association, February 2). It is unclear at the moment who these terror chiefs were, though it has been suggested Karim was in contact with Awlaki for more than two years.

By early 2011, Karim had become of greater concern to British police. His emails to his brother indicated that he was becoming restless and wanted to go abroad to fight. He had apparently spoken to his wife about this prospect, reporting to his brother that he “told her if she wants to, she can make hijrah [migration] with me and if the new baby dies or she dies while delivering, it is qadr Allah [predestined] and they will be counted as martyrs” (Press Association, February 2). He was also exchanging emails with Anwar al-Awlaki that indicated he had made contact with “two brothers [i.e. Muslims], one who works in baggage handling at Heathrow and another who works in airport security. Both are good practicing brothers and sympathize.” Awlaki was doubtless pleased to hear this, though he indicated, “our highest priority is the U.S. Anything there, even on a smaller scale compared to what we may do in the UK, would be our choice” (Daily Mail, February 2). It seems likely that the “brothers” referred to were those picked up by police in Slough a month after Karim’s arrest, though none were charged (The Times, March 4, 2010; Telegraph, March 10, 2010).

This message and others turned up after Metropolitan Police, with the assistance of Britain’s intelligence agencies, were able to crack the rather complex encryption system that Karim used to store his messages and information on his computers (Daily Star [Dhaka], February 15). Much of this now appears to be the foundation of the case against Karim beyond the charges he has already admitted to as a member of JMB. JMB has some history in the UK; acting on a British intelligence tip, Bangladeshi forces raided a charity-run school in March 2009 and found a large cache of weapons and extremist material. One of the key individuals involved in the charity was a figure who is believed to be a long-term British intelligence target. In another case, two British-Bangladeshi brothers allegedly linked to the banned British extremist group al-Muhajiroun were accused of giving the JMB money. [2] In neither case was there evidence the UK was targeted and it seems as though prosecutors in this current case are more eager to incarcerate Karim for his connections with Anwar al-Awlaki and AQAP than for his involvement with JMB abroad.

Notes:

1. Theresa May speech at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), November 3, 2010, https://www.rusi.org/news/,/ref:N4CD17AFA05486/.

2. “The Threat from Jamaat-ul Mujahideen Bangladesh,” International Crisis Group, Asia Report no.187, March 1, 2010, https://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/Files/asia/south-asia/bangladesh/187_the_threat_from_jamaat_ul_mujahideen_bangladesh.ashx.