Alleged Vote Rigging in Belarus and Paralysis of the Opposition

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 189

By:

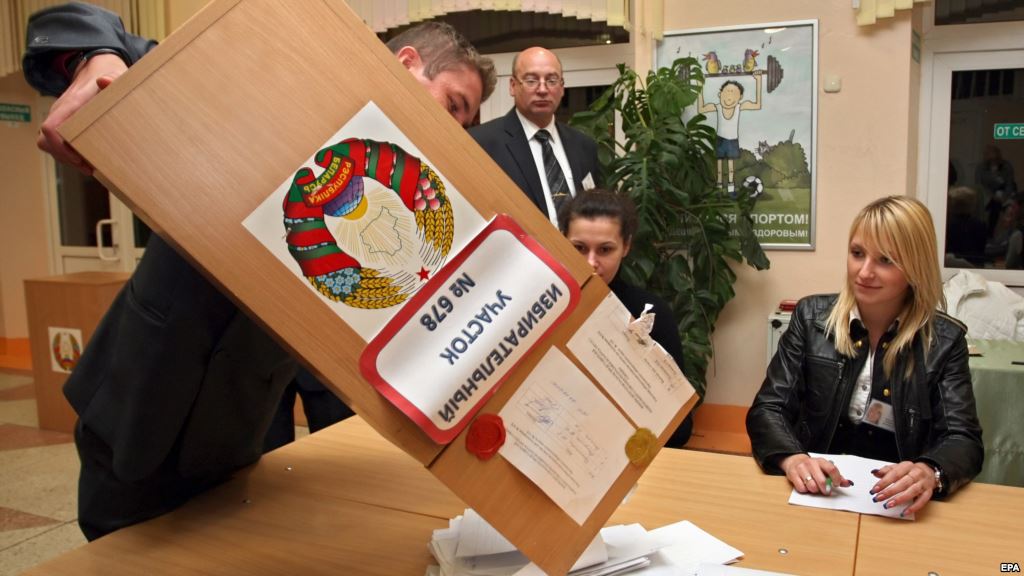

Belarus’s presidential election (held on October 11) appear to have generated two main responses. First, opposition-minded commentators practically unanimously opine that although the incumbent, President Alyaksandr Lukashenka, could have won the election hands down even without vote rigging, some 20 percent of votes may have been added to his actual support base; whereas, runner-up Tatyana Korotkevich was robbed of quite a few votes actually cast for her. Precinct 36, headquartered at the Center of Children’s Creative arts, in the city of Baranovichy, is the case in point. According to Makar Malinovsky, an independent observer, the initial results announced on the evening of October 11, which he documented, included 1,014 votes cast for Lukashenka and 230 votes (17.1 percent) for Korotkevich. In the morning, however, the results were “corrected,” so the final version included 269 more votes for Lukashenka and 130 fewer votes for Korotkevich; thus, she ended up with less than 7 percent of the local votes cast (Tut.by, October 15). Whether this case reflects a broader picture is unclear, but the evening “draft” of the electoral result fits some earlier assessments of Korotkevich’s rating (see EDM, October 7).

According to the analysis of the Belarusian Institute for Strategic Studies (BISS), five factors explain such alleged vote rigging. First, the authorities have no taste for making concessions. Second, winning the elections with a score well below the previous elections would have indicated that Lukashenka has become less popular. Third, it was essential to demonstrate the unity of the electorate in the face of an unprecedented economic crisis. Fourth, governing officials are evidently not even ready to establish a façade of democracy in the country. Finally, Belarus’s leadership counts on the West’s commitment to normalizing relations, so for Minsk it seemed enough to simply abstain from overt repression (Belinstitute.eu, October 13).

The second stream of post-election comments has focused on the allegedly unprecedented nature of the crisis in the Belarusian opposition. Thus, the same analytical document by BISS observes that Anatoly Lebedko, the leader of the United Civic Party, and Sergei Kalyakin, the leader of the left-wing party For a Just World party, initially mobilized their supporters to vote on October 11. Only after they miserably failed to collect the requisite number of signatures to register as presidential hopefuls, did they change their rhetoric and appeal for boycotting the elections. According to Valer Karbalevich of Radio Liberty, the opposition has neither a strategy nor any tactics for operating under the current situation (Svaboda.org, October 11). Meanwhile, analysis published by Carnegie Moscow Center’s Balazs Jarabik and Dzianis Melyantsou argues that “since the early 2000s, [Belarusian] opposition figures had participated in elections in order to enhance their standing within the opposition and boost their image in the West, rather than to compete against Lukashenka. That helps explain […] the opposition’s low popularity among the general public. The ‘new opposition’ [i.e., represented by Korotkevich] chose to make a play for support beyond its traditional electoral base […] by relying on moderate rhetoric and populist slogans… [As a result,] the traditional opposition tries to discredit the new generation” (Carnegie.ru, October 12).

Perhaps the harshest criticism of the old opposition was authored by Alexander Feduta, himself long a member of the opposition, who spent over three months in prison after the December 19, 2010, elections. Specifically, Feduta testified to the utter intellectual powerlessness of the Belarusian opposition parties, which had met on October 14 to discuss electoral law changes and called on the West to not recognize the legitimacy of the outcome of the election (Ucpb.org, October 14; Naviny.by, October 15).

In its turn, the major government newspaper Belarus Segodnya published an article titled “Five questions to the opposition from a young technocrat.” In it, Sergei Lavrinenko, a manager in one of the resident companies of the Minsk-based High-Tech Park, confesses than in his circle of colleagues and friends, democratic and Western-oriented viewpoints are dominant. “My friends develop software for Google, IBM, Coca-Cola, and launch startups from Moscow to San Francisco. Mentally and in terms of income, we are part and parcel of the so-called Western world… but our physical presence in Belarus makes us care about its [Belarus’s] fate.” Nonetheless, Lavrinenko and his close associates are not inclined to support the Belarusian opposition despite the fact that its slogans (free markets, Westernization and democracy) might suggest they represent common values. Indeed, de facto Westernized Belarusians—such as Lavrinenko—tend to become repelled by the opposition upon closer inspection (Belarus Segodnya, October 9).

Five major criticisms follow in Lavrinenko’s piece. First, the opposition pushes the West to outright not recognize Belarusian elections, and that only amplifies Belarus’s dependency on Moscow. Second, of all the presidential candidates this year, Lukashenka’s campaign platform actually came across to Lavrinenko and his colleagues as the most market-oriented—for instance, it featured the development of 4G and 5G mobile networks. Whereas the programs of the opposition were entirely populist and impractical (“we are for everything good”). Third, the opposition consists of either retirees or professional revolutionaries. In contrast, on Lukashenka’s side, there are such personalities as his aide Kiril Rydyi who, for four months, took courses at the University of Chicago (as a Fulbright exchange scholar); Vice Premier Vassily Matyushevsky, who graduated from London Business School; and Deputy Minister of Economics Alexander Zaborovsky, who attended four prestigious Western universities. Lavrinenko says he could find common language with these people easily, but nobody even remotely as qualified is available on the opposition side. The fourth reproach is that the opposition is economically illiterate. It, for example, criticizes the government for low retirement pension payments but, at the same time, decries high taxation specifically meant to prop up pensions. Lavrinenko attests that economic reforms are being conducted too slowly in Belarus, but (presumably under different leadership) they might not have been conducted at all. Finally, Lavrinenko questions the opposition’s ability to take power if and when Lukashenka is gone: “The art of politics is not in clashing with riot police; rather, one has to keep one’s head safe to formulate new ideas, to promote them in society, and to look for like-minded people in the government so that, in concert with them, these new ideas will be realized within the current system” (Belarus Segodnya, October 9).

That the Belarusian opposition is in bad shape is a near-universally accepted truth. Yet, rarely does criticism appear in such a matter-of-fact and lucid form as the recent critique by a self-proclaimed Westernizer and Belarusian private-sector manager.