Alternative Models for the Central Military Commission

Alternative Models for the Central Military Commission

The Chinese Communist Party’s 19th Party Congress, which starts on October 18th, will make major changes to the membership of key Party organs such as the Politburo (and the Politburo Standing Committee), the Central Committee, and the Central Military Commission (CMC) as older leaders retire, others are promoted or transferred to different positions, and new leaders are appointed. Within the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), many of these personnel moves have already been made, such as the announcement in late August that General Li Zuocheng, current PLA Army commander, has replaced General Fang Fenghui as Director of the CMC Joint Staff Department.

In addition to changing which individuals occupy key positions, the Party Congress also provides an opportunity to adjust the structure of the CMC to match the PLA’s post-reform organizational structure and the changes in responsibilities of the senior officers who lead different parts of the PLA. There are four likely models for a restructured CMC (a “status quo plus” CMC; an enlarged CMC; an operational CMC; and a management CMC), each with respective pros and cons. Decisions about how to restructure the CMC will provide new evidence about Chinese priorities, the relative influence of different parts of the PLA (and the officers chosen to lead those parts), and the state of civil-military relations in China.

The CMC is the supreme national organ in charge of military and defense affairs. Its major functions include formulation of military strategy, handling contingencies, building effective military forces, coordination of military, economic, political, and diplomatic strategies, and formulating military guidelines and policies. [1] Despite this consistent mission, the size and structure of the CMC have varied widely over the years, adapting to new strategic and political contexts. Party Congresses and associated plenums have typically been the occasion for major decisions on the CMC’s structure and membership.

In 2016, the PLA embarked on a major organizational restructuring that converted seven army-dominated Military Regions into five joint Theater Commands; removed the operational command role of the services and gave them “plan, train, and equip” responsibilities; and converted the four stand-alone general departments into parts of a reorganized CMC staff (China Brief, February 4, February 23). This restructuring was accompanied by extensive transfers of senior officers to lead the reorganized CMC departments, the services, and the theater commands. [2]

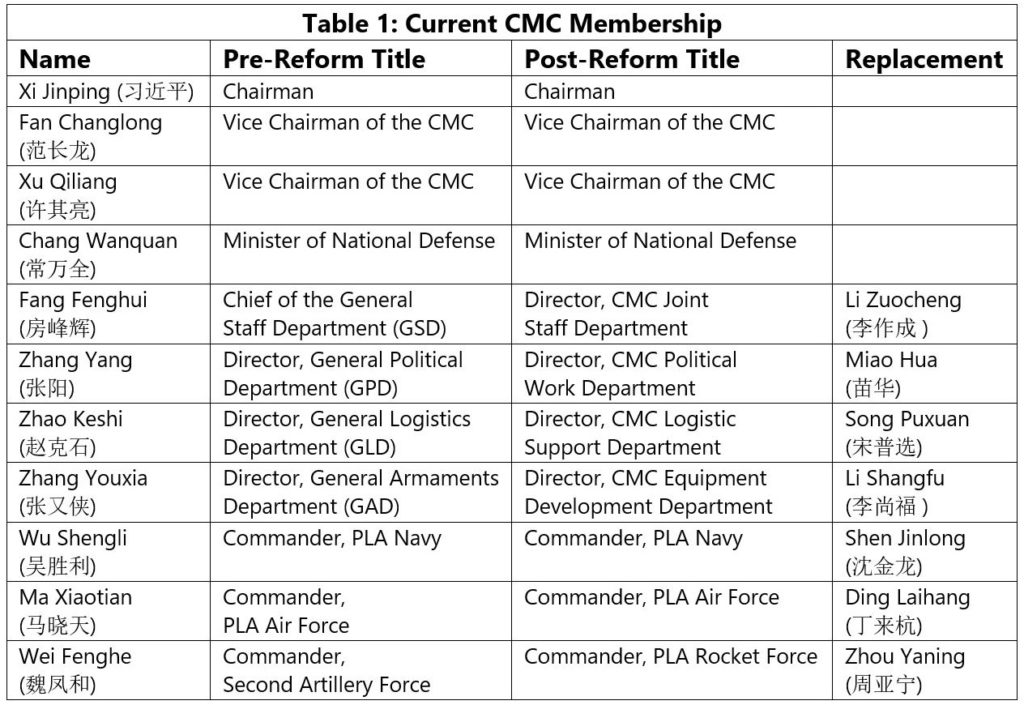

Despite this major organizational restructuring, there have been no changes to the formal membership of the CMC itself (see Table 1). Admiral Wu Shengli remains a CMC member, even though he has been replaced as commander of the PLA Navy by Shen Jinlong. Current CMC members Fang Fenghui and Zhang Yang are reportedly under investigation and are not included in the list of PLA delegates to the 19th Party Congress, but have not been removed from their CMC positions. General Li Zuocheng was named commander of the PLA Army (newly established as a separate service), but has not been made a member of the CMC, even though the commanders of the other services have that status. This reflects the practice of having CMC appointments be made by the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Committee.

Political considerations that may influence the structure of the CMC include:

- The imperative for the CCP to maintain control of the PLA and the desire to strengthen subjective and objective control mechanisms over the military. [3]

- Xi’s desire to centralize decision-making in his hands and not delegate major decisions, known as the Chairman responsibility system.

- The initial reforms provided jobs for all PLA senior officers to reduce potential opposition to reform. We may see changes to the grades of organizations and office-holders commanders as incumbents retire or transfer and are replaced by younger officers.

Operational considerations that may influence the structure of the CMC include:

- The right representation and expertise to offer good advice on high-level strategic/military decisions.

- Xi Jinping’s practical need to limit the time he personally devotes to military decisions.

- A membership that reflects the logic of PLA restructuring (e.g. new roles of services, theaters, and CMC departments) and a grade structure compatible with other parts of the PLA.

- Supporting a logical career progression that will give future senior PLA leaders the right mix of joint, operational, and staff experience.

- Potentially reduce size to improve decision-making speed.

Alternative Models for a Restructured CMC

A “Status Quo Plus” CMC: keep two military vice-chairs and Minister of National Defense, keep service commanders (and add the Army commander), and keep new heads of former general departments (which are now CMC departments).

This has the advantage of being closest to the existing CMC structure, and therefore being the easiest to implement. It would also represent the views of both the operational parts of the PLA (including the heads of the former general departments) and the services (with their army-building functions).

However, it would not necessarily match the political intent of the PLA reorganization (including the desire to rein in the power of the general departments, which were viewed as independent kingdoms that were vulnerable to corruption and which needed more supervision).

An Enlarged CMC: keep two military vice-chairs and Minister of National Defense, keep service commanders (and add the Army commander) and heads of former general departments; and add the five theater commanders.

This has the advantage of making the CMC a venue to reconcile operational demands (via participation of theater commanders and former general department heads) and army-building requirements (via service chiefs).

However, this enlarges the CMC significantly (which would slow decisions) and includes members who have three different grades in the current system (theater commanders are grade three, while most CMC members are grade two and the CMC vice-chairs are grade one).

An Operational CMC: remove heads of former general departments and service chiefs from CMC; build a smaller CMC focused on operational command and control. This model might retain the head of the CMC Joint Staff Department (which has an operational command role) and potentially add the Commanders of the Strategic Support Force and the Joint Logistics Support Force (which both have significant operational responsibilities).

This has the advantage of creating a smaller, more agile CMC that is better equipped to exercise operational control of joint forces and supervise the theater commands in wartime and contingencies.

A major drawback is that a smaller, operationally focused CMC would not have the right representation to perform the CMC army-building and strategic advice functions. The services and former general department heads would use this need to argue for their continued membership on the CMC.

A Management CMC: keep service commanders (and add the Army commander), remove the heads of former general departments, and reallocate supervisory responsibilities across the CMC vice-chairs (and possibly add a civilian vice-chair or give the Minister of Defense more responsibility). The CMC vice-chairs (and possibly an empowered Minister of Defense) would divide the operational, political, equipment, and logistics portfolios and have de facto supervision of the relevant former general department heads, who could be reduced in grade. The CMC General Office Director might be added as a CMC member to represent the views of all the CMC departments.

This has the advantage of making the CMC smaller (and thus better able to reach decisions) and reducing the influence of the former general department heads (and thus their ability to function as “independent kingdoms”). Empowering the Minister of Defense or adding a civilian vice-chair could significantly enhance civil-military integration, which is one of the major goals of the PLA reforms.

However, this model would substantially downgrade the role of the Director of the Joint Staff Department, who currently supervises operations and interacts regularly with foreign military leaders. (The CMC vice-chair with the operational portfolio might pick up these responsibilities.) This model would also empower the CMC vice-chairs, which could cut against the political goal of centralizing responsibility in the CMC Chairman’s hands and tightening CCP control over the military.

Other Considerations

There is a historical pattern of appointing the political successor to the CCP General Secretary to a civilian CMC vice-chair position two or three years before the successor takes over as General Secretary and Chairman of the CMC. Will Xi appoint a successor? Would the need to supervise the military provide a justification for Xi to stay on as general secretary and/or CMC chair after his two terms as General Secretary are over?

The Strategic Support Force is not a full service and has an operational support role rather than an operational warfighting function. Its director, therefore, might not be qualified for CMC membership.

The Minister of Defense has historically not had a major operational or military decision-making role. Could this change given the reform’s emphasis on civil-military integration? Could the Ministry of Defense take on more responsibility for weapons development, research and development, mobilization, and other areas that require interaction with other parts of the Chinese government and civilian industry? Alternatively, could a third CMC vice chair (possibly civilian) take on these roles? Many of these functions are now the responsibility of individual CMC departments or CMC commissions; having a senior PLA officer in charge of all them could improve coordination with the government and industry.

Will the former general departments be reduced to theater commander-grade organizations and their directors denied seats on the CMC? This would reduce their influence as “independent kingdoms,” but it might be difficult to downgrade the status of the Director of the Joint Staff Department.

The CMC General Office is listed first in protocol rank on the CMC staff. Does this qualify the Director of the General Office for CMC membership? Could the General Office Director be the sole CMC department head with CMC membership?

This analysis has focused on potential changes to the membership of the CMC rather than the equally important (but much harder to predict) question of which individual officers will be selected to fill which positions. Assessments of the capabilities, personal loyalty, and political reliability of individual officers may determine both which senior positions they are assigned to and what responsibilities are given to those positions.

Conclusion

China is almost certain to make at least modest changes in the membership of the CMC at the Party Congress, and the possibility of more dramatic changes cannot be ruled out. The most likely outcome is a “status quo plus” CMC with the addition of the PLA Army commander. This would be the least disruptive change, but would not fully adapt the CMC to meet the objectives of the PLA reforms. An enlarged CMC would be too unwieldy and an operational CMC would not be able to fulfill all the CMC’s responsibilities, so these options are unlikely. A management CMC that reduces the size of the CMC and empowers the CMC vice-chairs might be better adapted to the PLA’s new organizational structure and to the goal of increasing civil-military integration, but would require Xi Jinping to have great confidence in the personal loyalty and political reliability of the CMC vice-chairs.

Whatever structure China ultimately chooses will provide some insight into CCP and PLA priorities, the relative influence of different parts of the PLA (and the influence of the individuals chosen to command those parts), and the state of civil-military relations in China.

Dr. Phillip Saunders is Director of the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, part of the National Defense University’s Institute for National Strategic Studies. The views expressed are his own and do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Notes

- Tai Ming Cheung, “The Riddle in the Middle: China’s Central Military Commission in the Twenty-First Century,” in Phillip C. Saunders and Andrew Scobell, PLA Influence on China’s National Security Policymaking (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2015), 89.

- See Joel Wuthnow and Phillip C. Saunders, Chinese Military Reform in the Age of Xi Jinping: Drivers, Challenges, and Implications, China Strategic Perspectives 10 (March 2017).

- This distinction is from Samuel Huntington. Subjective control mechanisms attempt to ensure that the military will obey because it has the same political values and beliefs as civilians; objective control mechanisms are intended to ensure compliance by effectively monitoring military behavior.