Upcoming G20 Summit Spotlights Close but Complicated Relationship Between Xi and Indonesia’s Jokowi

Publication: China Brief Volume: 22 Issue: 20

By:

Introduction

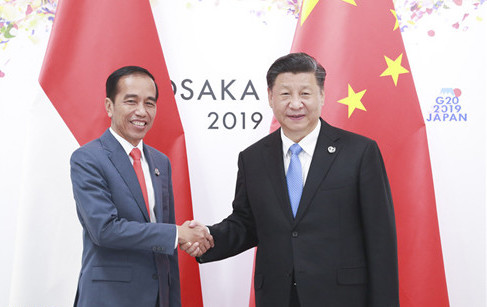

In a recent interview, Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo confirmed that both Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin plan to attend the upcoming Group of 20 (G20) summit in Bali from November 15-16 (Channel News Asia [CNA], August 19). The summit will mark Jokowi’s second in-person meeting with Xi this year, after a July summit in which Jokowi became the first foreign leader to visit Beijing after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (Gov.cn, July 27).

For many external observers, Xi’s attendance at the G20 summit represents yet another sign that Jakarta has shifted closer to Beijing, propelled by the close personal relationship between both leaders. Still, Jokowi’s relationship with the Chinese leader is close but complicated. Several issues including the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed rail line, territorial disputes over the Natuna Islands and China’s treatment of Muslim Uyghurs in Xinjiang continue to complicate bilateral relations.

Good Friends and Good Brothers?

“Indonesia and China are good friends and good brothers,” reported a Chinese government press readout from a phone call between both leaders last year (Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Ireland, April 20, 2021). Actions speak louder than words, and the frequent exchanges between the two leaders appear to affirm their steady, mutual friendship. Yet despite all his statements and visits purporting to signal interest in deepening ties with Beijing, Jokowi seems less interested in Xi Jinping himself and more interested in what a relationship with China can do for Indonesia.

The close feelings—officially at least—appear to be mutual. During the COVID-19 pandemic, both leaders spoke over the phone six times, including twice in 2022 before Jokowi’s July visit (Nikkei Asia, July 28). During his first two years in office, Jokowi met with Xi five times (The Jakarta Post, September 3, 2016). Moreover, following a week of global summits in 2014, Jokowi said that Xi—along with Japan’s Shinzo Abe—were the friendliest world leaders with whom he had met. [1] Notably, Jokowi’s answer named the leaders of Asia’s two largest and most powerful countries, both of which play a major role in bolstering Indonesia’s own developing economy. China is Indonesia’s biggest trading partner, with $124.4 billion in total bilateral trade in 2021, and its third largest foreign investor, accounting for 10 percent of total foreign direct investment (Observatory of Economic Complexity, accessed October 31). Japan is Indonesia’s third-largest trading partner and plays a crucial role in financing the Southeast Asian nation’s infrastructure development, including the ongoing construction of Jakarta’s rapid transit system (Observatory of Economic Complexity, accessed October 31; BKPM, accessed October 31). Jokowi’s strategic pragmatism certainly informs his public diplomacy. When asked why he felt Xi and Abe were the friendliest foreign leaders, Jokowi’s response was vague: “I don’t know… We talked a lot.” [2]

Such realism follows an extended Indonesian tradition of foreign policy nonalignment that stretches back to the republic’s founding in 1945. As an independent Indonesia emerged from the rubble of a hard-fought war against the Dutch, future Prime Minister Mohammad Hatta articulated two policies that would become the bedrock of Indonesia’s relations with other nations: “free and active” (bebas dan aktif) and “rowing between two reefs” (mendayung antara dua karang). In the context of the Cold War, Hatta sought to keep Indonesia out of the fractious conflict between Russia and America.

Jokowi has put his own spin on the tradition of nonalignment, refusing to take sides in divisive but distant conflicts and embracing a role as a global mediator. For example, in June, Jokowi became the first Asian leader to travel to Kyiv and Moscow to meet with Volodymyr Zelensky and Vladimir Putin, arguing that Indonesia could serve as a “bridge of peace” between Russia and Ukraine (Jakarta Globe, August 16). Before the Russia-Ukraine War, he brokered intra-Afghan peace talks at his presidential palace in Bogor, although such discussions mostly failed to produce lasting results (The Jakarta Post, March 14, 2018).

“For me ‘free and active’ is making friends with countries that can provide us with benefits,” the Indonesian leader has said (Australian Financial Review, August 28, 2020). For now, Jokowi believes that China can provide Indonesia with many advantages, including low-cost loans through the Belt and Road Initiative and substantial investment and trade flows. But other aspects of the bilateral relationship between Beijing and Jakarta indicate that the relationship is more complex and mixed than initially meets the eye.

No Rose Without Thorns

A host of historical issues like ideological differences, anti-Chinese violence in Jakarta, and the Indonesian government’s anti-Communist purge that caused the deaths of nearly one million people in the 1960s complicate bilateral China-Indonesia relations. Of late, three significant topics have challenged Jokowi’s seemingly cordial relationship with Xi: the Jakarta-Bandung railway project, territorial disputes over the Natuna Islands in the South China Sea, and the treatment of Muslim Uyghurs in Western China’s Xinjiang region.

First, the Jakarta-Bandung railway project remains a sensitive issue for Jokowi due to costly operational delays and concerns about Indonesia’s excessive debt burden to China. The project is not scheduled to finish construction until June of next year—four years behind its initial completion target of 2019 (Kompas, July 30). Previously, the project was hailed as one of the signature initiatives of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, linking two major cities and enabling Indonesia to become the first Southeast Asian nation with a high-speed train (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia). Nevertheless, enthusiasm for the project has dimmed due to excessive debts and cost overruns. Amid construction delays, the project’s price tag has increased by 23 percent from an already-hefty $6.07 billion (The Jakarta Post, August 1). For Jokowi, who has staked part of his political identity on a track record of successful infrastructure construction, the issues surrounding the project are particularly worrisome.

Second, the Natuna Islands dispute in the South China Sea has been a thorn in the side of Beijing-Jakarta relations since 2019. China claims sovereignty over the islands under its nine-dash line, a sweeping territorial claim rejected by both the Indonesian government and an international tribunal in The Hague in 2016 (Kompas, April 12, 2021). But in its public statements, Indonesia has sought to avoid confronting China over the Natuna Islands, reiterating that it is not a claimant in the South China Sea disputes and does not possess any overlapping maritime jurisdiction with China (CNA, June 19, 2020). The strategic value of the islands lies in their richness in natural gas and marine life. The number of fish caught in the region reaches nearly half a million tons per year (Voice of Indonesia, September 20, 2021).

One study from Indonesia’s premier graduate military academy called Beijing’s military threat to Indonesia’s sovereignty over the disputed Natuna Islands “highly imminent” (Twitter, January 30, 2021). Last year, Chinese law enforcement vessels conducted continuous patrols around a new Indonesian drilling site north of the Natuna Islands, and a Chinese survey ship monitored the seabed within Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone and continental shelf (Jakarta Post, December 21, 2021).

Still, Indonesia’s actions on this issue speak louder than its words. In a reflection of Jakarta’s concerns about China’s assertiveness in the Asia-Pacific, the Indonesian army expanded its annual Garuda Shield exercises this year to their largest-ever size, which included 14 total countries such as the U.S., Australia, Canada, Malaysia, and Singapore. For the first time, Japan participated in the drills that have now been dubbed “Super Garuda Shield” (U.S. Embassy & Consulates in Indonesia, August 3). The exercises in the South Sumatra province featured a combined force of 4,000 troops from the U.S. and Indonesia.

The third complicating factor in the Xi-Jokowi relationship is Beijing’s controversial treatment of Muslim Uyghurs in Xinjiang. This poses a particular challenge for Jokowi, who leads the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation. Jokowi has taken many steps to burnish his Islamic credentials in response to frequent domestic criticism that he does not sufficiently protect Muslim interests. For example, he has condemned Myanmar’s treatment of minority Rohingya Muslims and selected Ma’ruf Amin, a hardline Muslim cleric, as his vice president.

But his response to the ongoing human rights abuses in Xinjiang has been noticeably muted. In 2019, Jokowi avoided weighing in on the situation, despite domestic protests calling for Jakarta to adopt a tougher stance on China’s treatment of Uyghurs and other Muslims (Benar News, December 27, 2019). When asked two years later, Jokowi’s answer did not mention China by name and instead responded in general terms: “We must not contradict Islam with democracy… Islam and Indonesia respect each other. We expect all countries to do the same” (BNN, April 7, 2021). It is difficult to pinpoint the precise reason behind Jokowi’s tight-lipped responses on the Xinjiang issue. Many U.S.-based analysts argue that this reflects Indonesia’s deepening relations with China and his personal friendship with Xi. But a report from the Jakarta-based Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict raised other domestic political rationales, for instance, that Jokowi’s embracing a more assertive stance on the situation might further embolden Indonesia’s hardline Islamic right (South China Morning Post, June 23, 2019).

Conclusion

The November G20 summit will likely mark the first in-person meeting between Xi Jinping and President Biden since the American leader’s inauguration, and it is fitting that such an event will occur in Joko Widodo’s Indonesia. The 61-year-old leader has fashioned himself into an activist, honest broker on the world stage, recently proclaiming Indonesia to be at the “pinnacle of global leadership” while adhering to Indonesia’s longstanding foreign policy of nonalignment (Kompas, August 16).

In this polarized era of geopolitical competition, it is easy to view any move taken by other countries within the context of U.S.-China rivalry. In the case of Jokowi and Southeast Asia’s largest nation, however, the situation is more complex. While Jokowi wants to foster close ties with Beijing, he is more interested in elevating and advancing the interests of Indonesia. That narrow, self-interested lens is the one through which the world should ultimately understand Jokowi’s relationship with China and Xi Jinping.

William Yuen Yee is a research assistant with the Columbia-Harvard China and the World Program. He is the 2022 Michel David-Weill Scholar at Sciences Po in Paris, where he is pursuing a master’s degree in International Governance and Diplomacy. You can follow him on Twitter at @williamyuenyee.

Notes

[1] See Ben Otto and Joko Hariyanto, “Fast Friends for Jokowi: Xi and Abe,” Wall Street Journal, November 17, 2014.

[2] Ibid