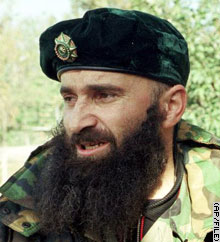

BASAEV GONE, BUT MOSCOW STILL HAS HEADACHES IN THE NORTH CAUCASUS

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 3 Issue: 133

By:

The July 9 death of Chechen warlord Shamil Basaev from an accidental explosion — not a Russian-planned operation — removes the Chechen rebels’ most charismatic and probably most ruthless commander from the scene. Although Federal Security Service (FSB) Director Nikolai Patrushev claimed, “The effort became possible thanks to our operative actions abroad in the first place in the countries where weapons are gathered for Chechnya,” in fact Basaev was killed when an explosive-laden truck in his convoy accidentally detonated. To add to the drama of Basaev’s death, the FSB promptly announced that Basaev was planning an operation to coincide with the July 15-17 G-8 meetings in St. Petersburg. While this is entirely possible and characteristic of Basaev, it also is entirely possible that this is merely another example of FSB mythmaking.

In recent years FSB reports and those of other Russian security agencies about the number of people fighting Russia have seemed more a guesstimate than the result of rigorous intelligence gathering. Most official reports said that only a few hundred guerillas, ranging anywhere from 500-1,500, opposed Russia in Chechnya. But in 2005 alone 3,000 rebels surrendered or went over to the Russian side, suggesting that many more guerillas were present than admitted. That record also suggests that Moscow’s policies for the republic, carried out by Chechen President Alu Alkhanov and Prime Minister Ramzan Kadyrov, were meeting with measurable success.

Just one day before Basaev died, Kadyrov had claimed that there are only a few dozen guerillas left, along with some 60-70 foreign “mercenaries,” to face his 17,000-strong police force, which he claims is “excellently trained and experienced in combat action.” Kadyrov also regretfully admitted that he was not involved in the purported operation against Basaev, thereby casting doubt on the FSB’s self-serving propaganda and implicitly conceding that Moscow does not fully trust him. But his boasts merit careful scrutiny.

While several Russians and Chechens in official positions suggested that Basaev’s death might lead to the end of the insurgency against Moscow, the fact remains that the entire North Caucasus is aflame, and Russia still has no solution to its problems. Moreover, in Chechnya there are some 50,000 Russian MVD troops whose mission is as much to watch Kadyrov and his forces as it is to fight the insurgency. Kadyrov and his private guard, the Kadyrovtsy, who at times resemble Basaev more than they like to admit in their unbridled terrorism and penchant for kidnappings, are, according to Russian observers, “out of control.” Hence the Russian troops need to watch them and keep them out of sensitive operations. There were many opportunities for the Russians or the Kadyrovtsy to track Basaev, who traveled with a Russian passport, and yet they never got him despite the $10 million bounty on his head.

This free pass for Basaev suggests that the earlier reports of tacit collusion among terrorists and Russian forces were correct, that this practice continues, and that the competence of the Russian forces is lower than Moscow claims. Certainly operations are still continuing against the Chechen rebels, and Basaev had promised to bring the war into Russia territory this summer. And now without any leader to control the Chechen insurgents, we may actually see an increase in the number of unplanned “anarchic” attacks from Basaev’s remaining colleagues, directed against their enemies, rather than their surrender. It remains unclear to what degree his death might impede or facilitate the conduct of such operations. But it does seem likely that another leader will emerge while Russia simultaneously will undertake efforts either to cut Kadyrov down to size or to just cut him down. The key point here is that neither peace nor internal security can be assured, nor is there a truly legitimate regime in Chechnya that can rule peacefully. While Chechnya remains the justification for Putin’s attacks on democratization efforts, the results of his campaign in the region are hardly edifying. Nor is it likely that Basaev’s death will reduce the growing unrest in the North Caucasus.

Although official Russia likes to attribute the unrest in the Caucasus in general — and in Chechnya in particular — to Wahhabism, in fact the cause of the unrest remains long-standing Russian misrule and oppression. This situation ultimately led to unbridled Islamic terrorism as practiced by Basaev and his like-minded colleagues, but it is doubtful that Kadyrov and his thugs represent a better prospect or that anyone else has a solution to the problems of the North Caucasus. Undoubtedly Putin has won a big battle here, even if inadvertently, and cut down a tall tree of Chechen resistance. But it is unlikely that a people who have fought Russia for more than 200 years will simply accept defeat now or that Russia knows how and will bring about a peace based upon a legitimate order that compels assent rather than fear either in Chechnya or in the North Caucasus.

(RTR Planeta TV, July 10; Interfax, July 8, 10; Channel One Television, July 10; www.president.ru, July 10)