Belarus’s Parliamentary Elections and Opposition Prospects

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 35

By:

Executive Summary:

- Belarus’s government outlawed opposition parties in anticipation of last week’s parliamentary election, contrasting previous elections that had offered a platform for opposition parties to spread their views.

- Oppositionists have primarily been forced into exile, which raises doubts about how effectively they can communicate with their potential base within Belarus to organize action.

- While the Belarusian government may appear firmly in control, the country’s lack of national consolidation is a significant vulnerability that is a problem for both the government and the opposition.

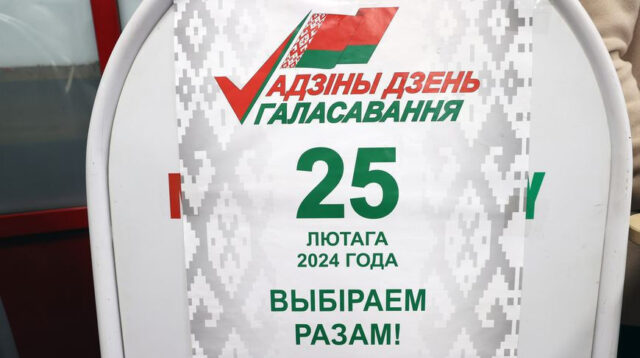

On February 25, the parliamentary elections in Belarus predictably elicited contrasting reactions. Alexey Avdonin, an analyst at the Belarusian Institute for Strategic Studies, claimed that “words of gratitude” are due “to our citizens … who fulfilled their civic duty and cast their votes, thereby not only supporting the candidates but also expressing direct support for the policy that is now being pursued in the Republic of Belarus” (SB, March 1). Statistical reports indicate that, of the 110 newly elected members of the Belarusian House of Representatives, only 20 were reelected from the previous parliament. Seventy members of parliament (MP) are part of the four registered parties, whereas the remaining 40 are unaffiliated. Out of the affiliated MPs, 51 are members of the Belaya Rus Party, only one MP is younger than 31, and 40 percent of MPs work for the state (SB, March 1). The national turnout was 73 percent, but there was only a 61-percent turnout in Minsk (Belta, March 1). Altogether, 110 MPs were chosen out of 265 candidates (RBC, February 26).

Anatoly Glaz, spokesperson of the Belarusian Foreign Ministry, delivered a sarcastic response to Matthew Miller, spokesperson of the US State Department, condemning the “Lukashenka regime” for conducting “sham elections” (US Department of State, February 25). “We spent the whole night together with the Central Election Commission of Belarus looking for citizen Miller in the voter lists to determine which district commissions should respond to his complaint,” declared Glaz. “We did not find him. Then, we held in-depth consultations with lawyers to understand what the US State Department has to do with the elections in our country. We also found no connection. After that, we tried to find an international law defining the United States’ role as an evaluator of the electoral process in independent countries and found nothing of the sort” (Belarusian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, February 26).

According to leading opposition journalist Artyom Shraibman, the electoral campaign was most boring, even by the standards of President Alyaksandr Lukashenka’s 30-year rule. That is because the experiments with pluralism were discontinued. Although the elections were rigged in the past, the opposition still had a chance to use the electoral campaign to promote their views (CarnegieEndowment, February 26). During the summer of 2023, however, all opposition parties were outlawed (Gazeta.ru, October 2, 2023). In the run-up to the most recent elections, Minsk still appeared nervous despite the sterilized political environment. A ban was issued against photographing ballots, the members’ names of local electoral commissions were no longer published, and polling stations were no longer set up at Belarusian embassies abroad (Official Website of Belarus, February 25). Belarusian citizens not residing in the country had to return to Belarus to vote in a designated polling station on election day (Belarusian Central Election Commission, January 23). Minsk also did not invite observers from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), though the organization routinely monitors elections, even in Turkmenistan (OSCE, January 8).

The above indicates that Lukashenka is no longer interested in legitimizing his rule in the eyes of the West. It is more important for him to convince himself that the 2020 post-election protests were an aberration and that Belarusians eventually returned to their senses and electoral discipline (see EDM, November 2, 2020). Above all, the 2024 parliamentary elections have disrupted the cyclic pattern of Belarus’s domestic politics. The 2006, 2010, and 2020 presidential elections ended in mass protests. Those were followed by repressions, which were succeeded by political thaws. The latter enabled voters to mobilize around new opposition-minded leaders. This political pendulum has stalled, with elections assuming the same role they played in the Soviet Union. According to Shraibman, that can change only under two circumstances: new leadership and escape from Russia’s control. He concluded that neither of these circumstances is likely to come to pass in the foreseeable future (CarnegieEndowment, February 26).

A statistical analysis of online surveys conducted by opposition-minded sociologist Yury Drakakhrust of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty faulted Lukashenka’s suggestion that the 2020 protest was driven by a demand for power from a successful group of entrepreneurs and information-technology personnel. Paradoxically, this suggestion coincided with the opposition’s, although moral assessments of the market in question did not. According to Drakakhrust, the protests were driven by the regime’s governance, which neglects political self-expression and may trigger future protests (BelarusPolls, February 29).

The extent to which the current Belarusian opposition will consolidate its base is yet to be seen. In Shraibman’s pessimistic opinion, the political energy of 2020 is running out. It is unclear how the opposition, primarily pushed into exile, can communicate with its potential base within the country. This calls into question the opposition’s fight for democracy and its support from Western sponsors. Many in the West no longer see the opposition as a reckoning force within Belarus. The opposition’s activities are effectively being reduced to protecting Belarusians abroad, crowdfunding for political prisoners, and reminding the international community about Belarus’s existence. Not many people are required to perform such functions (Zerkalo, February 29).

While the perspective of Belarus based on a democracy-versus-autocracy showdown appears accurate, it is worth re-examining. While this pattern fits a tenacious popular narrative, it may occasionally miss the mark. Several months before the crackdown on post-election protests, Jamestown analyst Yauheni Preiherman pointed to a lack of national consolidation as Belarus’s major vulnerability (NashaNiva, April 14, 2020). “Do not rock the boat of Belarusian statehood” was his appeal to the opposition. However, the appeal was shrugged off. The problem is that one cannot possibly facilitate national consolidation by alienating a large segment of society whose outlook is not indiscriminately West-friendly but not anti-Belarusian either. Any political group with the potential to bring positive change to Belarus should figure out how to deal with that segment. Otherwise, that potential will never become a reality.