Briefs

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 19 Issue: 13

By:

Militants Target Chinese Nationals in the Sahel and Nigeria

Jacob Zenn

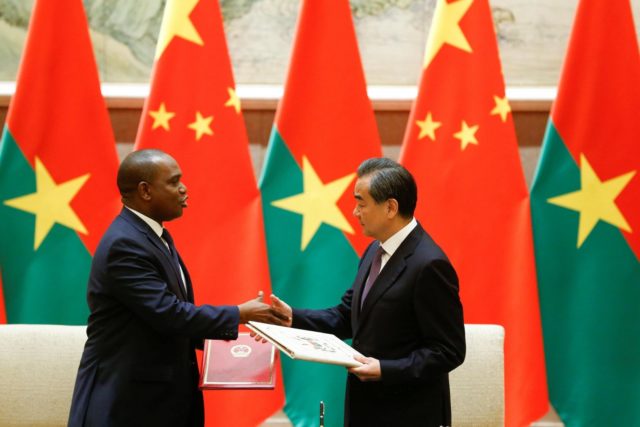

China is increasing its influence in West Africa. Most recently, on June 11, China’s State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi stated that Beijing plans to extend the Belt and Road Initiative to Burkina Faso in coordination with the latter’s government. Further, China would provide support to Burkina Faso’s efforts to combat COVID-19 and to counter terrorism (news.cgtn.com, June 11).

Only three days before Wang Yi’s announcement, however, two Chinese gold miners were abducted in Niger, not far from the Burkina Faso border (allafrica.com, June 7). Although there has been no claim of the attack, Islamic State in Greater Sahara (ISGS) and al-Qaeda-affiliated Group for Supporters of Islam and Muslims (JNIM) both operate frequently in that border area. Niger’s governor in the province of the abduction did not attribute the abduction to ISGS or JNIM, but they remain prime suspects (Twitter.com/ChinaDailyWorld, June 8). Since Burkina Faso cut its ties to Taiwan and established diplomatic relations to China in 2018, China has provided agricultural support, such as for rice production, and begun mining operations for gold, uranium, and oil in the border area between Niger and Burkina Faso. As Beijing’s presence in these areas grow, instances of jihadists and other armed bandits targeting Chinese nationals can only be expected to increase (chinaafrica.cn, June 13).

Meanwhile, on April 7, two Chinese gold mine employees were also abducted in Osun State, southwestern Nigeria (globaltimes.cn, April 7). This attack was too far south to be attributable to Boko Haram, but was near oil-producing areas where various militants have long operated. Only one day before the gold mine abduction, on April 6, Nigerian authorities rescued two other Chinese agriculturalists in Ogun State in southern Nigeria (vanguardngr.com, April 6).

The above cases highlight how, as Chinese economic expansion continues in West Africa, security will become a greater concern for its nationals and possibly, as in Burkina Faso, lead to greater security collaboration between Beijing and the regional governments. Nevertheless, China has still not become a major focus of jihadist attacks or rhetoric. The country, for example, was only briefly featured in an al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) video in 2009 that demanded revenge against China for its response to violence involving Uyghurs and Han Chinese in Xinjiang Province, but that video did not lead to any subsequent attacks on Chinese nationals (alarabiya.net, July 14, 2009). Chinese citizens have only incidentally been caught up in AQIM attacks, such as the 2015 Radisson Blu hotel attack in Bamako, Mali that killed 27 people, including three Chinese nationals (fmprc.gov, November 25, 2015).

Likewise, Boko Haram abducted nine Chinese engineers in northern Cameroon in 2014, but did not target them for their nationality nor did the group make any claims about their capture being related to Chinese foreign policy (France24.com, May 17, 2014). The Chinese engineers were, therefore, targets of opportunity and were eventually released for a ransom. It is thus not Boko Haram, but bandits and other criminals generally, who have become the greatest threat to Chinese nationals in West Africa thus far (scmp.com, January 28, 2014). With the diverse threats to its citizens, Beijing will have to reassess whether a security dimension must increasingly accompany the Belt and Road Initiative and other economic projects in West Africa.

***

Mystery Surrounds Car Bombing on Venezuela-Colombia Border Military Base

Jacob Zenn

On June 16, videos emerged from Cúcuta on Colombia’s eastern border with Venezuela of a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED) detonation at the Colombian National Army’s 30th Brigade military base (Twitter.com/Jjuscategui, June 16). A reported 36 soldiers were injured in the explosion, which Defense Minister Diego Molano described as a “vile terrorist attack” during an emergency visit to the base (telesurtv.net, June 15). Molano also blamed the left-wing rebel group, the National Liberation Army (ELN), for the VBIED attack, although without providing any specific evidence for that allegation.

The ELN is a natural suspect in the attack. In 2019, for example, the ELN carried out a similar VBIED attack on a police academy in Bogota that killed 21 people and injured 68 more (semana.com, January 18, 2019). Further, in 2020, the ELN announced that it was abandoning its ceasefire with the Colombian government, which means that the group is now actively conducting attacks against the army (France24.com, April 27, 2020). The 2019 attack was the most deadly VBIED attack in Colombian history since 2003, when a similarly styled explosion was set off by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) near a Bogota nightclub, killing 36 people (eltiempo.com, February 7). Thus, it is rare, but not unforeseen, for left-wing rebels in Colombia to conduct VBIED attacks.

What was rare about this latest VBIED attack in Cúcuta, however, was that ELN denied any responsibility for the attack and said it had “nothing to do” with it (elespectador.com, June 18). This stands in contrast to the ELN’s 2019 VBIED attack claim, when it stated that “the operation carried out against said installations and troops is lawful within the law of war, as there were no non-combatant victims” (cbc.ca, January 21, 2019; laopcion.com.co, January 21, 2019). Thus, without any evidence proving ELN’s involvement in the Cúcuta VBIED attack or any claim from ELN, Molano’s assertion that ELN was responsible is not verifiable.

If not the ELN, then drug traffickers operating along the Colombia-Venezuela border could possibly be responsible for the attack. However, such a VBIED attack would be unprecedented for drug traffickers in that area and makes them an unlikely suspect. Therefore, the attack remains a mystery and a potential source of conspiracy theories, given that Molano instinctively blamed the ELN. Such an allegation, for example, might be intended to provide just cause for a renewed army offensive against the group.

The VBIED attack also attracted additional attention from the United States because its troops were training Colombian soldiers in Cúcuta (marinecorpstimes.com, June 17). Although the U.S. embassy in Bogota issued a statement assuring that no U.S. soldiers were “seriously injured,” it noted U.S. military personnel were with a Colombian unit at the time of the explosion. Investigations remain ongoing regarding the attack, and it is likely the U.S. will be involved considering the VBIED attack posed a direct threat to U.S. personnel in the volatile border region between Colombia and Venezuela. It must also be recalled that in 2019 the U.S. had been involved in supporting politicians and activists opposing the Maduro regime in Venezuela, including through operations in Cúcuta (miamiherald.com, February 8, 2019).