China and the United Arab Emirates: Sustainable Silk Road Partnership?

Publication: China Brief Volume: 16 Issue: 2

By:

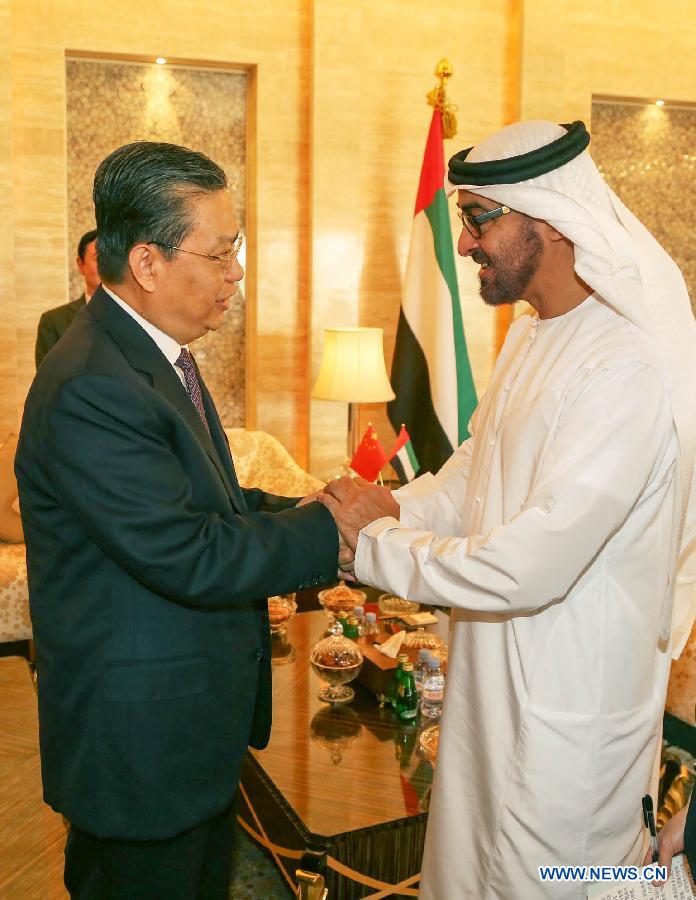

Among Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is emerging as an important player through its relationship with China. Despite Saudi Arabia and Egypt’s perceived dominance given their size and historic role in the Middle East, the UAE’s increasing prominence as a regional trade and investment hub, along with its energy diversification strategy could prove more fruitful in the long-run for China’s foreign policy goals. One obvious reason for building partnerships with Gulf states remains China’s insatiable energy demands. The December 2015 visit of Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces of the UAE, signaled new avenues for cooperation (Xinhua, December 7, 2015). Recent reports on China-Arab relations preceding the visit by Xi Jinping to the Middle East mirror many themes expressed in last year’s “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) vision (China Daily, January 13; China Daily, January 15; NDRC, March 28, 2015). [1] The UAE is already playing a role in Chinese efforts to internationalize the renminbi, and green energy may provide a more balanced and sustainable partnership than Silk Road partners looking primarily for loans and infrastructure development. The UAE delegation visit to China highlighted three prominent themes: currency cooperation, joint investment, and solar-based green energy.

The UAE officially established relations with China in 1984 and cooperation between China; the UAE has continued since with 36 agreements currently in place with China (The National, December 12, 2015). China was one of the first countries to sign a bilateral investment treaty (BIT) with the UAE in 1993 and the UAE is a founding member of the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank (AIIB). [2] The primary English-language daily newspaper in the UAE dedicated an entire page to earlier visits to China by Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, founding father of the UAE (The National, December 14, 2015). Other local Emirati commentary underscored the historic relationship with China calling attention to the original Silk Road, Zheng He, and early trade in pearls and porcelain (The National, December 13, 2015). Previous visits to China by Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan occurred in 2009 and 2012 and relations between China and Dubai have been increasing steadily (Emirates 24/7, December 9, 2015; China Brief, May 29, 2015). [3] The UAE has become an important hub for the Gulf and ports such as Jebel Ali provide an important access point for China’s efforts to build “smooth, secure and efficient transport routes connecting major sea ports along the Belt and Road” (NDRC, March 28, 2015). Unlike its regional neighbors, the UAE offers infrastructure with global trade access and, most importantly, domestic stability.

Currency Cooperation

In late December, China “renewed its renminbi swap agreement with the UAE in its latest move to internationalise the yuan” (The National, December 14, 2015). The UAE likely was chosen as a currency partner because of its wealth, stability, and previous cooperation with China on investment. The announcement also comes on the heels of the recent IMF decision to include the renminbi in its basket of currencies, a strategically important moment for China (IMF, November 30, 2015). Both of these steps are consistent with the OBOR’s guidance to “expand the scope and scale of bilateral currency swap and settlement with other countries” in order to “deepen financial cooperation . . . building a currency stability system, investment and financing system and credit information system in Asia” (NDRC, March 28, 2015).

China and the UAE signed their first bilateral currency swap agreement in 2012 for up to 35 billion renminbi (PBOC, January 17, 2012; $5.5 billion, at 2012 exchange rates). The UAE agreement was not as large as currency swap arrangements made with close trading partners such as Hong Kong, Singapore, or Korea, which range from 300 to 400 billion renminbi but the UAE was the first GCC member to sign a swap agreement. [4] Qatar followed suit in November 2014. [5] Unlike currency swaps intended to alleviate a liquidity crisis, China’s arrangements serve an entirely different purpose. China’s swap agreements are “a method to promote bilateral trade and direct investment between China and each partner in local currencies as opposed to the US dollar.” [6] Renewing the China-UAE agreement is another sign of the continuing internationalization of the renminbi.

The currency swap agreement indicates China’s inroads in the Gulf but it is important to note that the UAE currency, the dirham (AED), remains fixed against the U.S. dollar. Thus, the agreement primarily helps Chinese firms conducting business in the UAE but over the long-term should foster the UAE’s ability to act as regional trade hub regardless of the currency used by firms. The announcement from the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) highlighted the goal of the renminbi as a standard investor mechanism outside China’s borders, in this case expanding the experiment to the UAE (PBOC, December 14, 2015). [7] UAE reporting focused on how the agreement helps it achieve its goal of becoming a “regional trading hub for yuan-denominated investment” (The National, December 15, 2015). Efforts to bolster Abu Dhabi and Dubai as export and trading hubs are not new, but the ability to conduct business in both dollars and renminbi fosters the UAE’s central financial role in the Gulf. All four Chinese banks have branches in the UAE and the currency bargain eases cross-border trade and investment for Chinese firms thus bolstering China’s global financial image (The National, December 12, 2015).

The currency arrangement with the UAE will be one to method of assessing China’s commitment to renminbi internationalization goals. Given the increasing pressure on the Chinese economy, which is likely to continue in 2016, continuation of these swap arrangements indicates China’s dedication to currency reform—despite challenges facing its domestic economy.

Regional Investment

The United Arab Emirates may not yet have the international clout of its neighbors but the Emiratis have conducted air strikes in conjunction with the counter-Islamic State campaign and have sent ground troops into Yemen (The National, December 14, 2015; The National, December 30, 2015). The UAE’s outsized role in security complements the country’s role in economic initiatives. Minister of State Dr. Sultan al-Jaber has touted the country’s role in OBOR and highlighted the UAE’s status as “a founding member of the China-backed” AIIB (Xinhua, December 10, 2015; The National, December 9, 2015). The UAE contributions to the AIIB are slightly less than Saudi Arabia and Iran’s but higher than GCC peers Qatar and Kuwait. [8] In the Crown Prince’s press release, he stated that China’s “regional initiatives … will reshape the very fabric of our wider region’s economic future” (Xinhua, December 14, 2015).

One concrete outcome from the Crown Prince’s visit to China is the creation of a new joint sovereign wealth fund. The Emirate of Abu Dhabi already has four major sovereign wealth funds and overall the UAE has eight. [9] During meetings in Beijing, Xi Jinping stated that the “joint investment fund is a highlight of cooperation” (Xinhua, December 14, 2015). The joint enterprise between China Development Bank, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange, and Mubadala will be worth $10 billion (The National, December 14, 2015; NDRC, December 15, 2015). The Chinese announcement listed traditional energy sources (传统能源) and high-end manufacturing (高端制造业) as areas for cooperation as well as clean energy (清洁能源) (NDRC, December 15, 2015). Separately, Mubadala also “signed a non-binding agreement for international exploration and production” with China National Petroleum Corporation (The National, December 15, 2015).

Sustainable Energy Partnership?

The recent Paris climate change agreement focused international attention on sustainable energy. Some of the most unlikely, yet strongest proponents of green energy may be small Gulf states. The UAE has begun numerous clean energy initiatives and publicly announced goals meant to diversity the UAE’s energy supply. The Abu Dhabi Economic Vision 2030 explicitly notes the country’s high demand for energy and the government believes that “diversifying energy sources is a key strategy to ensure future energy security.” [11] Energy diversification is consistent with the AIIB’s purported “lean, clean, and green” approach and the UAE believes that “Beijing can cement UAE’s position as key player and architect of [the] GCC’s energy future” (AIIB Website; The National, December 14, 2015).

Dubai has been proactive about engaging China and green energy initiatives could be an effective way to broaden and deepen the relationship. [12] In November 2015, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Vice President of the UAE and Ruler of Dubai “launched the Dubai Clean Energy Strategy 2050, which aims to make the emirate a global centre of green energy” (The National, November 29, 2015). During the inauguration of the second phase of the Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Solar Park, “plans for a new free zone called the Dubai Green Zone” were also announced (The National, November 29, 2015). The scale of this new zone is not yet apparent but just as the Jebel Ali Free Zone has been the centerpiece of the UAE’s integration into global trade and shipping networks the hope is that the Dubai Green Zone will become a hub for sustainable energy technology. This latest zone affords China early opportunities for its emerging solar industry.

In Sharjah, the emirate north of Dubai, the government’s focus is also on solar and Chinese firms are directly engaged in the process. During the China Trade Week exhibition in December, the Sharjah Investment and Development Authority – referred to as Shurooq – met with Chinese representatives to discuss joint ventures in solar. According to the official in charge of investment promotion at Shurooq, “The talks are at an early stage but there is great potential for the solar sector” with Shurooq estimating that the Sharjah “renewables market has the potential to reach $51 billion” (The National, December 7, 2015). Since the Sharjah talks are in their infancy the Shurooq officials would not cite any specific Chinese companies involved in the negotiations but Jiangsu-based Changzhou Almaden (常州亚玛顿) recently broke ground on a solar panel factory in Dubai (The National, December 7, 2015; Changzhou Almaden).

As the joint investment fund took shape, Abu Dhabi also sought to move forward its energy initiatives. Abu Dhabi-based Masdar sent representatives in the UAE delegation to China. [14] Masdar’s chief executive noted during the visit that “international partnerships are key to the diversification of energy sources . . . [and] long-term energy security and sustainable development” (The National, December 15, 2015). Masdar and the Chinese firm Vanke “agreed to explore opportunities for cooperation” and “a separate agreement for research cooperation was signed between Masdar Institute and Tsinghua University” (The National, December 15, 2015). With both Abu Dhabi and Dubai committed to energy diversification, ample opportunities exist for solar-based enterprises.

Conclusion

China and the UAE may be opposites in geographic and population size but there are numerous avenues for cooperation between the growing Persian Gulf power and Asian economic giant. Announcement of further agreements are not expected immediately, but future progress on the agreements reached in Beijing will provide a sign of whether China and the UAE are committed to energy diversification, joint investment, and currency cooperation. Given Beijing’s One Belt, One Road and Maritime Silk Road strategy, the UAE has the potential to be a key partner for China’s foreign economic policy. Despite its small size, the wealth, stability, and centrality of the UAE make it a strategic hub for Chinese engagement in the region.

April A. Herlevi is a doctoral candidate in the Politics Department at the University of Virginia, currently residing in Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates. Her research interests include international political economy, foreign direct investment, China-Middle East relations, and Chinese economic and foreign policy. Prior to entering the Ph. D. program at UVA she was an East Asia analyst with the U.S. government based in Washington, DC.

Notes

1. Xi Jinping will visit Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Iran, likely in an effort to balance Sunni-Shia divides in the region (China Daily, January 16).

2. For the China-UAE BIT, see UNCTAD’s Investment Policy Hub. For AIIB founding members, see https://www.aiib.org/html/pagemembers/.

3. China Brief, Volume 15, Issue 11 provides a summary of Dubai-China trade relations and the role of the Jebel Ali Free Zone (Jafza). Dubai Ports World, the company that manages Jafza, also operates container terminals in Hong Kong and Qingdao and is building ports in Tianjin and Yantai (DP World).

4. Steven Liao and Daniel McDowell, “Redback Rising: China’s Bilateral Swap Agreements and Renminbi Internationalization,” International Studies Quarterly 59: pp. 401–422, September 2015. Agreements and swap amounts through October 2013 are in Table 2, p. 406.

5. Xinhua, China Daily, November 3, 2014; for Qatari announcement from the PBOC.

6. Liao and McDowell, “Redback Rising,” September 2015, p. 405.

7. The text (人民币合格境外机构投资者) was in reference to the “renminbi qualified foreign institutional investor” (RQFII) mechanism with the implications that the renminbi will eventually become a standard international currency.

8. The UAE accounts for 1.6 percent of shares among regional members. Saudi Arabia and Iran contributed 3.4 percent and 2.1 percent, respectively. Qatar and Kuwait is shares are approximately 0.8 and 0.7 percent. Author’s calculations based on AIIB Articles of Agreement, June 29, 2015.

9. Author interview, Abu Dhabi, May 20, 2015. Abu Dhabi’s four major sovereign wealth funds are the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA), the Abu Dhabi Investment Council (sometimes referred to as ADIA II), the International Petroleum Investment Company (IPIC), and Mubadala. Other Emirati funds include the Investment Corporation of Dubai, Senaat, Emirates Investment Authority, and the Ras al Khaimah Investment Authority (RAKIA).

10. The Abu Dhabi Economic Vision 2030, November 2008.

11. China is now one of the top markets for Dubai (China Outbound Tourism Research, November 11, 2015; The National, June 17, 2014). There are now “over 3,000 Chinese companies registered in the UAE” and many of them are related to tourism or corporate events (China Daily, June 3, 2015).

12. Masdar is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Mubadala, one of the sovereign wealth funds owned by the Abu Dhabi government (Masdar). Minister of State Dr. Sultan al-Jaber, chairman of Masdar, and chief executive Dr. Ahmad Belhoul were both part of the UAE delegation to China (The National, December 14, 2015).