China’s Media Controls: Could Bloggers Make a Difference?

Publication: China Brief Volume: 7 Issue: 8

By:

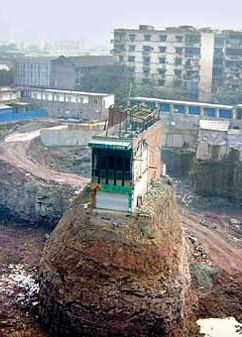

For several weeks recently, China’s bloggers, internet news sites and even state-run media chased a story that captivated millions of Chinese. A small brick house perched on a precarious island of earth in the middle of a huge construction site had become a symbol of individual property rights in the face of government-backed development projects. For a brief moment, property owner Wu Ping became a nationwide celebrity. Her house became known as a “nail house,” coined after a Chinese expression describing those who are willing to stand up to authority. As many Chinese have been made painfully aware, such nails can be pulled or hammered down. Wu Ping was lucky, however, and her timing and dramatic flair paid off. A court announced that Wu Ping and her husband would receive a new apartment and space for a new business as well as monetary compensation. The house was subsequently demolished, and Wu Ping, who had briefly become a spokesperson for many others facing similar evictions and demolitions, suddenly became unavailable for comment. The police ordered major websites to stop covering the story, and the state-run media fell silent.

That the tightly controlled Chinese media even covered such a story came as much of a surprise, but Wu Ping’s nail house emerged just as the National People’s Congress was passing a new property rights law that purports to protect individual homeowners. This may have been more of an exceptional case than a breakthrough for the Chinese media, given that tens of thousands of Chinese fall victim to government-backed land development schemes and receive little compensation. The lenient treatment of Wu Ping may have helped the government to make a propaganda point, namely that the government respects private property, at least in certain cases. Yet, the “nail house” case may also reveal that downtrodden individuals in China are becoming more willing to challenge the system through unconventional means. Some bloggers are still trying to keep the story alive and have found a similar case in Shenzhen, although it has not received the same attention that Wu Ping’s case received.

China’s Biggest Uncovered Story

China’s breakneck economic growth is one of the biggest stories in the world today. Nevertheless, that growth has created another important story, one that is less extensively covered. According to sources from the Ministry of Labor and Social Security, some 40 million Chinese farmers have lost their land to urbanization over the previous decade, with additional millions set to suffer a similar fate (Xinhua, July 25, 2006). Local officials are grabbing land for development projects, profiting from rising property values and paying farmers compensation that is far from adequate. In response, the farmers are protesting in large numbers, and in 2006, the Ministry of Public Security reported 87,000 protests, riots and other “mass incidents,” many of them occurring in rural areas far from large cities like Chongqing, where the nail house incident occurred (People’s Daily, January 20, 2006). At the same time, many farmers and others are increasingly trying to use the country’s legal system to defend their rights. They are aided by a new breed of Chinese activists, including a number of outspoken lawyers, whose work is largely ignored by the state-run media. Cyber-dissidents in the form of bloggers and journalists have also taken up their cause, but a number of them are now in prison, and it has become increasingly dangerous for Chinese journalists to cover the unrest. The Paris-based organization Reporters Without Borders (RSF) has reported about 40 incidents of physical attacks on journalists, many of them carried out by gangsters, thugs and migrant construction workers hired by local officials and businessmen. At least 31 journalists were in jail in China as of January 1 [1].

When President Hu Jintao took power more than three years ago, some Chinese intellectuals, including journalists, hoped that he would open up China’s political system and allow the Chinese media to begin covering major stories such as corruption and rural unrest. A high point for Hu among “liberal” intellectuals came in the spring of 2003, when he fired China’s health minister as well as the mayor of Beijing for covering up the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic and seemed to promise more transparency regarding major issues. In fairness, coverage of major health threats, such as HIV/AIDS and most recently bird flu, has at least slightly improved. Nevertheless, the media face even stricter controls under Hu than was the case under his predecessor Jiang Zemin.

By early 2004, the honeymoon between the government and the press was over as the Communist Party began another crackdown on newspapers and television stations that dared to report on the Chinese society’s “dark side.” Beijing also began to police the internet more actively. After the “color revolutions” in countries such as Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan in the first half of 2005, Hu began warning of the danger of dissident groups and non-governmental organizations working with “anti-China forces abroad” to undermine Communist Party rule.

In 2006, lawyers and judges were banned from speaking to foreign journalists about “mass incidents” involving farmers and the unemployed. RSF concluded in its annual report that journalism was “being forced into self-censorship” and had become the most dangerous job after mining and police work. At the same time, defamation suits against journalists became more common during the year, and according to RSF, “as preparations got under way for the next Communist Party Congress in October 2007, public security arrested at least 12 journalists and placed scores more under surveillance.”

Commercialization Has Not Weakened Controls

Some hoped that the growing commercialization of the Chinese media would result in a loosening of controls, but that has not been the case. A groundbreaking report released by Freedom House last year explains how the Chinese government has modernized the media system to meet business criteria and the needs of China’s political leaders, but not the needs of its journalists [2]. The government monitors journalists through a national registration system and mandatory participation in ideological training sessions. Officials deliver content requirements increasingly via telephone, but also on occasion in propaganda circulars. The government has been using a vaguely worded “national secrets” law with greater frequency against journalists in recent years, the report notes, though “a far more common source of concern is a libel suit.” Newspapers that attempt to do investigative reporting lose most of these cases, especially since the laws allow plaintiffs to decide where the case will be tried. Plaintiffs “typically choose their own jurisdiction, where they have strong personal connections in the courts” [3].

Propaganda officials constantly remind journalists of what they consider the most sensitive topics. The taboo list ranges from coverage of dissidents and ethnic minorities to high-level corruption and unrest among farmers and workers. Off-limit subjects also include religious groups not recognized by the government and several historical topics, such as Mao Zedong’s “anti-rightist” campaign of 1957 and his responsibility for the millions of deaths caused by the Great Leap Forward and subsequent famine. The killing of demonstrators near Tiananmen Square in 1989 is, of course, still on the taboo list [4].

Commercialization has permitted advertising and more varied and colorful editorial content, with once-taboo subjects such as sex and crime being reported upon and discussed. Driven by profits, tabloid journalism and news of the weird—two-headed piglets or ducks that drink beer—is in; the more graphic the pictures of a crime scene showing slit throats, the better. Commercialization has also led to “performance bonuses” that are based upon the journalists’ ability to please both consumers and party bosses. The need to earn bonuses, which can amount to more than half of a journalist’s salary, leads reporters to engage in an approach to journalism that shuns any hard-hitting investigative journalism on issues of political sensitivity, resulting in what The Wall Street Journal once described as “new and improved propaganda.”

A Test Case: AIDS Coverage

The case of HIV/AIDS coverage in China over recent years serves as such an example. Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao have embraced a policy of greater transparency on this issue, and the government no longer blacks out the subject completely. Yet, according to Chinese AIDS activist Hu Jia, the government is split over the issue. President Hu and Wen want to give more prominence to the issue, but Li Changchun, the Politburo Standing Committee member who is in charge of propaganda, wants to play it down. Li was acting governor and then governor of Henan province in the early 1990s, when a local government-sanctioned blood plasma donor business triggered an HIV/AIDS epidemic in the province. With the support of Luo Gan, the Standing Committee member who oversees the police and security services, these two Politburo heavyweights are in turn allied with local officials, such as those in Henan who have tried to cover up the HIV/AIDS-blood plasma connection [5].

According to Gao Yaojie, China’s leading AIDS activist, blood plasma businesses have spread to other provinces. China’s state-run media avoid this issue, however, and focus instead on the less controversial elements of HIV/AIDS—transmission of HIV infections through sex or intravenous drug use. When non-governmental organizations have attempted to shed light on the situation, their complaints have been routinely ignored by the media. Earlier in April, when 62 of China’s NGOs made comments opposing a government monopoly over AIDS funding, Chinese state-run media and websites failed to even mention it.

Bloggers to the Rescue?

Given these restrictions and omissions, the internet and Chinese bloggers may be the best hope for a breakthrough toward a freer flow of information in China. The way in which the nail house story developed might be instructive in this regard. Blogs were the first to cover the story—no one seems to be sure which blog struck first—followed by people who took cell phone pictures that quickly reached the web. Such a stream of grassroots information proved to be difficult for the government to control.

To be certain, the government has been very effective at blocking major websites and using undercover policemen to infiltrate and manipulate chat rooms. It is now putting an even greater effort into monitoring blogs and video exchange sites. According to Xinhua, China was expected to have 60 million bloggers by the end of 2006, but few bloggers dare to take on sensitive issues (Xinhua, May 6, 2006). Moreover, China’s blog tools include filters that block “subversive word strings” and the authorities pressure companies that are operating these services to control content. They employ “armies of moderators” to clean up blogging content. Sensitive words like “freedom” or “democracy” are censored. With 52 people currently in prison for expressing themselves online, self-censorship among bloggers are in full force, with most blogs selectively dealing with pop culture and personal matters [6].

Despite all this, a significant number of people on the internet in China are both tenacious and tech-savvy. Radio Free Asia’s (RFA) readers and listeners, for instance, regularly request information on how to use proxies, and the story of Qu Chao shows how some people have succeeded in beating the system. Qu, a disabled person from Jilin province who had offended officials by taking his complaints to Beijing, had his property destroyed, failed to obtain redress in the courts and was imprisoned in a detention center. While in detention, he and other prisoners managed to listen to RFA via shortwave radio. As soon as he was released, Qu launched online queries through chat rooms about how to reach RFA. Late last month, one volunteer posted his story on an RFA blog, and in response, a RFA reporter called Qu and began checking into the facts involved in his story.

Budding “citizen journalists” have also begun to emerge through the chaos of the blogosphere. On April 9, bloggers revealed the story of an incident that had erupted in Beijing. A farmer decided to drive his tractor into the city, possibly to carry his complaints to the heart of the Chinese capital. Groups of “irregular policemen”—a euphemism for thugs—hired by the city and labeled as “city administrative teams” began to pursue the man and his tractor. They then rammed a car into the tractor and dragged the farmer away. While the journalist who witnessed the scene had her camera smashed, bloggers managed to pick up the story by taking pictures with cell phones. The bloggers presented an interesting story backed up by their pictures, but many details were missing, including the story behind the farmer’s actions as well as his fate [7].

Could it be that bloggers will now fill the gap and provide some of the investigative journalism that is missing from the equation? Unlikely, say leading Chinese journalists. Despite greater freedom that has been promised to foreign journalists during the period leading up to the Beijing Olympics in 2008, Chinese journalists are operating under rules that could get stricter rather than looser. In an interview earlier this year with RFA, Li Datong, former editor-in-chief of a groundbreaking investigative magazine that belonged to the China Youth Daily, expressed doubt that the Olympics would bring any positive change. Li himself was fired last year after publishing a number of sensitive articles, and his magazine supplement, Freezing Point, was shut down.

China’s leaders judge the news based upon whether it supports or undermines their power, said Li. “Pornographic and vulgar things don’t threaten their political power, so they don’t care; they allow it to spread unchecked. But if…they think they will suffer political harm, they will search and destroy….” In Li’s view, the media are not effectively monitoring corrupt officials. “The (media) reports about corruption are all produced after the case is resolved. They are not reports based on the media’s knowledge and experience. What significance do such reports have? None whatsoever…Recently, the party secretary in Qingdao was sacked…What happened? No one knows. It’s a mystery.” Li acknowledges that the internet is more flexible than the traditional media, but, he says, “the reporting one can do on the internet is often limited…It is random and piecemeal. Does this discourse have any impact? It has no impact…Only professional journalists have the professional skills to do these kinds of investigations” [8]. Yet, the nail house case shows that bloggers can in fact break a story, provide the momentum required to keep it running longer than newspapers or major websites and stay with it until the end. In addition, more Chinese seem willing to stand up like nails—which again like Chongqing could prove to be a potent challenge to the state.

Notes

1. See the Reporters without Borders’ “China – Annual Report 2007,” available online at: https://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=20779.

2. Freedom House Special Report: “Speak No Evil; Mass Media Control in Contemporary China,” by Ashley Esarey, February 2006.

3. Ibid.

4. Dan Southerland’s testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission: “The State of Chinese Media and the Internet in China,” April 14, 2005.

5. Radio Free Asia (RFA) English Web page: “Chinese AIDS Activist Defies Police,” by Dan Southerland, April 5.

6. Reporters Without Borders’ “China – Annual Report 2007.” Also see “China to have 60 million bloggers by end-2005,” Reuters, May 6, 2006 and “China says number of blogs tops 34 million,” Associated Press, September 25, 2006.

7. Duowei Boke: Beijing Chengshi Guanlizhe Yue Li Yue Niude Yangzi. “Duowei Blog: Beijing city managers are becoming more and more arrogant.”) See three bloggers’ comments, April 9.

8. RFA investigative reporter Peter Zhong’s interview with editor Li Datong, broadcast January 10, 2007.