China’s Strategy toward Central America: The Costa Rican Nexus

Publication: China Brief Volume: 9 Issue: 11

By:

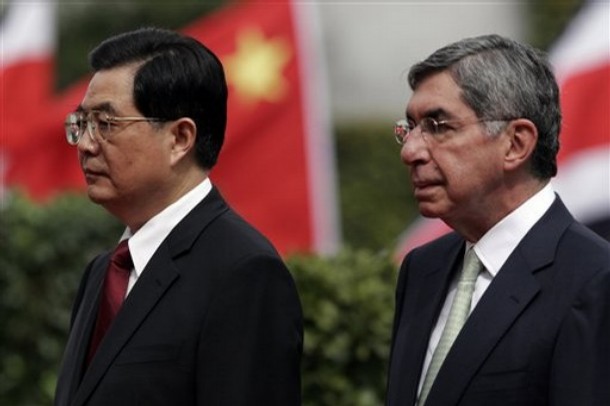

When Chinese President Hu Jintao visited Costa Rica last November and announced that the two countries were initiating free trade talks, it marked the beginning of a new phase in China’s courtship of Central America. Indeed, China’s striking economic growth over the last decade has positioned Beijing as a crucial economic partner of all of Latin America’s major economies, with total bilateral trade exceeding $140 billion last year. Yet, Central America largely remains a missing link in this agenda. While the commodity exporting countries of South America have profited handsomely from their relationship with China, Central America has felt the sting of Chinese competition in the manufacturing sector. More crucial, from Beijing’s perspective, is the fact that the Central American region constitutes the most significant bloc of countries in the world that continues to maintain diplomatic relations with Taiwan. As a result, Chinese leaders are puzzled as to how to improve relations with Central American nations that are largely peripheral to China’s economic concerns but central to Beijing’s mission of peeling away Taiwan’s remaining trappings of state sovereignty, which include its diplomatic partners overseas.

Latin America is half a world away from the decades-long conflict simmering in the Taiwan Strait, but the diplomatic tussle between Taiwan and China remains a red-hot issue in the Caribbean and Central America. Beijing rigorously promotes its “One China” policy, which means that non-recognition of the Taiwanese government is a prerequisite for conducting formal diplomatic relations with the PRC—in effect forcing other governments to choose between Beijing and Taipei. Although each of the Latin American countries involved in this geopolitical chess match have little individual clout, together they make up the most significant group of states caught in the cross-Strait tug-of-war, representing 12 of the 23 countries that recognize Taiwan. Today, Taiwan preserves official relations with six Central American countries (i.e. Guatemala, Belize, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Honduras, and Panama), five Caribbean countries (i.e. the Dominican Republic, Haiti, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines) and Paraguay—the lone holdout in South America.

After nearly a decade of fairly stable alliances, the battle between China and Taiwan in Latin America really began to heat up in 2004, as China’s economic growth better positioned it to compete head-to-head with Taiwan in the field of “dollar diplomacy,” which entails wooing potential diplomatic allies with promises of trade, investment and official development assistance. The island nation of Dominica defected to China in 2004, followed by Grenada in 2005, but Taiwan struck back in 2007 by wooing the newly-elected government of St. Lucia. Yet, Beijing notched a major victory later that year by winning over Costa Rica, which was the first Central American country to recognize China. For China, which is always sensitive to U.S. perceptions of its involvement in Latin America, Costa Rica’s benign image in Washington allowed China to sidestep accusations that its outreach to Latin America focuses primarily on leftist countries that have hostile relations with the U.S. It would have been far more attention-provoking for Beijing to begin its Central American outreach with Nicaragua’s left-wing government, for example, which would have set Washington’s neoconservatives on edge.

In March 2008, Taiwan’s hard-fought presidential election produced political shockwaves that sent ripples all the way to Latin America when Ma Ying-jeou, a mild-mannered 57-year old lawyer led the Kuomintang (KMT) nationalist party back to power for the first time since 2000. Unlike his predecessor Chen Shui-bian, who sympathized with Taiwan’s independence movement, Ma has pledged to improve relations with the People’s Republic of China. He has said he opposes both pursuing Taiwan’s independence and negotiating reunification with China, arguing that “the status quo is the best choice.” These statements have been watched very closely by the dozen Latin American and Caribbean countries that have diplomatic relations with Taiwan, as many leaders wonder whether the time is ripe to jump ship and seal relations with China. In recent months, China’s relations with Taiwan have edged toward détente, including opening trade and travel ties, as well as a landmark decision by China to allow Taiwan’s participation as an observer at the World Health Organization. Ma’s conciliatory stance toward China has in fact lowered the temperature of cross-Strait competition in the Americas. Nevertheless, when President Ma planned a tour through Central America from May 27 to June 2, a spokesman for China’s Foreign Ministry firmly restated Beijing’s position: “The Chinese government adheres to the one-China policy and opposes Taiwan having official exchanges with any country. This position remains unchanged" (Xinhua News Agency, May 21).

The Case of Costa Rica

Costa Rica has now emerged as the stress test for both local and regional neighbors in evaluating the impact of China’s expanding partnerships in this distant but vital part of the world. In June 2007, the decision of Costa Rican President Oscar Arias to revoke relations with Taiwan and embrace China was a major coup for the Chinese leadership. At the time, it prompted speculation that Costa Rica’s switch would precipitate a broader “domino effect” that could lead to many of the six other countries in the Central American isthmus to switch sides in favor of Beijing. Instead, a nearly two year period of hiatus has settled in after several years of frenetic activity, and no other Latin American or Caribbean country has followed in Costa Rica’s footsteps. The potential explanations for this include inattention from China, Taiwan’s active diplomacy, the lessening of tensions in the Taiwan Strait, and a “wait-and-see” attitude by other Central American governments, who want to know how China’s relationship with Costa Rica evolves before embarking on a similar path. What has become clear over the past two years, however, is that China is focusing on creating a model relationship with Costa Rica that will serve as a regional example of the benefits of formalizing ties to Beijing.

Upon announcing the establishment of diplomatic relations between Costa Rica and China, President Arias described his decision as “an act of foreign policy realism which promotes our links to Asia. It is my responsibility to recognize a global player as important as the People’s Republic of China” (Xinhua News Agency, June 7, 2007). China promptly dispatched Wang Xiaoyuan, an experienced Chinese diplomat who had served as the PRC’s ambassador to Uruguay, to set up a new embassy in San José. At first blush, Arias, who won a Nobel Peace Prize in 1987 for his role in helping to end the wars then raging in Central America, seemed an unlikely candidate to be the region’s first leader to recognize China. An advocate of democracy, he frequently spoke out against communism and tangled publicly with Cuba’s Fidel Castro. But the tremendous financial rewards that his nation reaped from China soon proved to be an important component of his realpolitik. Papers released under court order in the fall of 2008 revealed that a secret deal had been struck between China and Costa Rica during the negotiations over diplomatic recognition. In exchange for Costa Rica’s move to expel Taiwan’s diplomatic mission, Beijing agreed to buy $300 million of Costa Rican bonds and provide $130 million in aid to the country, as well as provide scholarships to enable study in China (New York Times, September 12, 2008).

Now the two countries are embroiled in trade talks as Costa Rica seeks to become the third country in the region, after Chile and Peru, to sign a free trade deal with China. Costa Rica was among the six countries (including the Dominican Republic) that signed the Central American Free Trade Agreement (known as DR-CAFTA) with the United States in 2005, but it will be the first Central American country to negotiate a trade deal with China. The first round of talks took place in Costa Rica last January with follow-up talks in Shanghai in April. The process is scheduled to be completed before Arias leaves office in 2010, but even with a formal trade arrangement bilateral trade has zoomed upwards to $2.9 billion in 2008, a more than thirty-fold increase since 2001. China has also offered to help Costa Rica build an oil refinery to improve its access to energy (Xinhua News Agency, November 19, 2008). Of course, Costa Rica’s deepening relationship with China has circumscribed its ability to deal with issues that are sensitive to the Chinese leadership beyond just Taiwan. For example, in August 2008, Arias asked the Dalai Lama, a fellow Nobel Peace Prize winner and the spiritual leader of Tibet, to cancel a planned private visit to Costa Rica. Arias cited “scheduling problems,” but it is clear that he knew that a visit by the Dalai Lama would have sacrificed Costa Rica’s chance to host Hu Jintao later that year.

Patience is a Virtue

Given the increasing weight of the Chinese economy in the global system overall, all of Taiwan’s allies in the Western Hemisphere are under continually building pressures to formalize their budding ties with Beijing. This makes the fact that there has been no additional movement in Central America toward recognizing Beijing all the more intriguing. At this juncture, the loss of even one more Central American ally would represent a damaging reversal for Taiwan that could further cripple Taiwan’s claim to sovereignty. The Costa Rica example demonstrates, however, that China’s regional strategy has shifted toward providing more succulent carrots (rather than punitive sticks), and there is little question that Taiwan is desperately trying to prevent additional defections. China appears to have bet that developing an intensive, multi-faceted relationship with Costa Rica may have a powerful demonstrative effect on other countries in the region—assuming that Costa Rica is viewed as reaping substantial benefits. Guatemalan President Alvaro Colom may be too absorbed in his country’s contentious politics to risk a China diversion, but other governments in El Salvador and Honduras are certainly eyeing Beijing, even as they play host to President Ma of Taiwan. The spring election of Mauricio Funes of the left-wing FMLN as El Salvador’s new president has prompted an especially frantic wave of outreach from Taiwan, including an impromptu post-election visit by the Taiwanese foreign minister, in an effort to keep another Central American country from falling into China’s grasp. Since the election of Daniel Ortega in November 2006, Nicaraguan officials have been careful to assure Taipei that cooperation between the two countries will continue. China has attempted to put pressure on tiny Belize by working through the Caribbean Community, a regional organization of mainly English-speaking governments who have mostly eschewed Taiwan in favor of China. Recently elected Panamanian president Ricardo Martinelli vowed to review his country’s relations with China and Taiwan during the election campaign, but his instincts as a successful businessman may pull him toward China.

Chinese leaders are eagerly interested in expanding their success with Costa Rica to other parts of Central America, but in the short term they are not going to force the issue. Rather, China correctly views Costa Rica’s 2007 conversion as a major victory that they have time to savor and deepen before conducting their outreach to other countries in the region with renewed intensity. China’s carefully calibrated patience toward Central America helps to explain why even President Ma’s upcoming visit to the region has not caused much of a stir in Beijing. When it comes to the battle for diplomatic recognition in Central America, China feels confident that time is on its side.