Chinese Covert Social Media Propaganda and Disinformation Related to Hong Kong

Publication: China Brief Volume: 19 Issue: 16

By:

Introduction: “Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior” Related to the Protest Movement in Hong Kong

On August 19, the microblogging platform Twitter announced the suspension of 936 accounts originating in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which the company identified as part of an “information operation focused on the situation in Hong Kong.” The company stated that these accounts “were deliberately and specifically attempting to sow political discord in Hong Kong, including undermining the legitimacy and political positions of the protest movement on the ground,” and further asserted that “we have reliable evidence to support that this is a coordinated state-backed operation” (Twitter Blog, August 19).

On the same day, Facebook announced that—acting on information provided by Twitter—it had taken down fifteen accounts, pages, or groups “involved in coordinated inauthentic behavior as part of a small network that originated in China and focused on Hong Kong.” The company further asserted that the organizers “behind this campaign engaged in a number of deceptive tactics… to manage Pages posing as news organizations, post in Groups, disseminate their content, and also drive people to off-platform news sites… Although the people behind this activity attempted to conceal their identities, our investigation found links to individuals associated with the Chinese government” (Facebook Newsroom, August 19).

These announcements were followed three days later by a statement from Google, the parent company of Youtube, that it had taken down 210 channels on the video posting site “as part of our ongoing efforts to combat coordinated influence operations.” The company stated that this action was taken “when we discovered [that] channels in this network behaved in a coordinated manner while uploading videos related to the ongoing protests in Hong Kong [which was] consistent with recent observations and actions related to China announced by Facebook and Twitter” (Google Blog, August 22).

The exposure of this coordinated covert operation has shed further light on how the social media realm has emerged as one of the newest fronts for PRC state-directed propaganda and disinformation efforts intended to bolster the interests of the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP). [1] It also reveals much about the narratives surrounding the Hong Kong protest movement that the CCP wishes to promote to both domestic and foreign audiences. As such, the themes and methods of this social media campaign merit closer examination.

PRC Covert Propaganda and Disinformation Through Social Media

The covert social media campaign employed by PRC entities against the Hong Kong protest movement is not the first of its kind: the Russian government’s use of social media disinformation to manipulate opinion and sow divisions in other countries has been well-established. [2] Furthermore, PRC actors have themselves sought to covertly use both traditional and social media to influence public opinion in places such as Taiwan (Straits Times, April 2; Taiwan Sentinel, April 8). However, the accounts suspended in August are noteworthy for attempting to direct disinformation towards a broader international audience.

Propaganda and Disinformation Themes

Material drawn from the suspect social media accounts avoids substantive discussion of issues motivating the Hong Kong protest movement (the draft extradition law, universal suffrage, etc.), relying instead on emotive language and imagery intended to stimulate patriotic feelings, fear, or disgust. Five propaganda themes stand out prominently in the PRC covert social media campaign surrounding events in Hong Kong:

- All Chinese persons, whether within or beyond the borders of the PRC, stand in unified support of Chinese government policies towards Hong Kong.

- The protest movement is secretly controlled by the United States—which seeks to bring about a “color revolution” (颜色革命, yanse geming) intended to overthrow the Hong Kong city administration, to separate Hong Kong from the rest of China, and to weaken China as a whole.

- The protestors are terrorists, equipped by the United States, who employ brutal violence and potentially lethal weapons against both police officers and the general public in Hong Kong.

- The Hong Kong police are courageous heroes protecting the public from violence and anarchy.

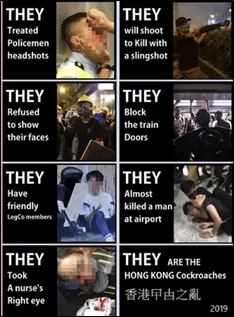

- The protestors are identified with various types of verminous insects.

The first four points are all consistent with PRC overt propaganda. However, in official propaganda outlets the second and third points are generally made with oblique hints rather than explicit statements. For example, an August 12 commentary in the flagship CCP newspaper People’s Daily asserted that foreign “black hands” had “attempted to interfere in China’s internal affairs by stirring up trouble, creating chaos and instigating riots in Hong Kong…[t]hey have used people in Hong Kong as ‘chess pieces’ and ‘cannon fodder’ for their political schemes… [t]hey instigated extreme radicals to make trouble, trained them, provided them with weapons, and made false speeches to ignite hostile emotions among the people” (People’s Daily, August 12). The “black hands” are not specifically named, but it is clearly implied that they belong to the United States.

The fifth point listed above—the dehumanization of protestors as insects—is not a feature of official PRC propaganda. However, this is a consistent theme in covert social media material, as well as in overtly hosted (if not explicitly endorsed) material, in which protestors are repeatedly labeled as “cockroaches” (曱甴, yuezha) or “locusts” (蝗虫, huangchong or 蚂蚱, mazha) (see accompanying images). Such an identification is intended to provoke disgust—and potentially, to carry the implication that such vermin deserve extermination.

Language and Platform Selection, and Their Potential Significance

Many of the suspect accounts featured content in English, as well as in Chinese script (see accompanying images). The reasons for this are unclear, but it may indicate either that the content was intended to shape opinion abroad, and/or that it was directed towards bilingual target audiences in Hong Kong and overseas diaspora communities. Some of the suspect English-language accounts and content were presented as if coming from sources from outside China (CBS San Francisco, August 20)—and therefore may have been intended to support a narrative of widespread international outrage against the protestors.

The use of these particular platforms is also noteworthy: Western-operated social media sites like Twitter and Facebook are restricted within the PRC (although not in Hong Kong), and sites and apps such as Weibo and WeChat are far more commonly used by Chinese consumers. Therefore, the covert social media campaign was likely intended primarily to target opinion overseas, rather than at home. However, if the campaign was directed to an international audience, the outlandish propaganda themes and the crude nature of the English-language content (poor grammar, etc.) likely limited its overall effectiveness.

Use of Virtual Private Networks by Campaign Participants

Ironically, one of the deceptive methods associated with the social media disinformation campaign was the use of virtual private networks (VPNs), a common tool employed to disguise the internet protocol (IP) address associated with particular web searches and postings. Although they are still used within the PRC, VPNs are officially banned, and their usage can result in fines, lowered “social credit” scores, and potential arrest. However, their usage was a hallmark of the suspect accounts targeted in August: as announced by Google, “We found use of VPNs and other methods to disguise the origin of these accounts and other activity commonly associated with coordinated influence operations” (Google Blog, August 22). Twitter stated that “many of these accounts accessed Twitter using VPNs [and some] accounts accessed Twitter from specific unblocked IP addresses originating in mainland China” (Twitter Blog, August 19).

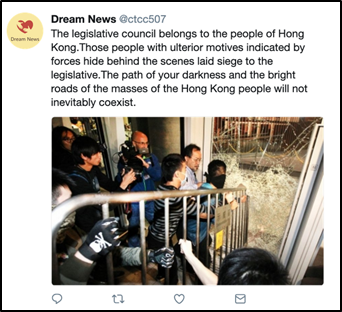

PRC Overt Propaganda Channeled Through Twitter

The account and channel suspensions announced in August by Twitter, Facebook, and Google do not affect the overt use of these platforms by PRC state entities. Through their overt accounts, PRC media outlets may continue to spread propaganda and disinformation about the Hong Kong protest movement: either through direct news coverage, or by hosting content from nominally independent third parties. (For two recent examples of such Twitter content by PRC state-controlled newspapers, see the images immediately above.)

However, while these PRC state entities will still be free to post news content through their accounts, their use of future social media advertising may be at least partially curtailed. On the same day that it announced the account suspensions, Twitter further announced that it would cease accepting advertising from “state-controlled news media entities”—defined as entities subject to state editorial control, but omitting publicly-funded outlets with independent editorial control, such as Voice of America or Deutsche Welle (Twitter Blog, August 19).

Conclusion

The actions taken by Twitter, Facebook, and Google in August revealed an unusual display of solidarity and coordinated action on the part of three of the world’s biggest social media and internet content companies. The action taken by these U.S.-based social media companies cuts against an ethos of unregulated speech that these companies have invoked in the past—and more importantly, impacts their corporate profits. These companies are likely reacting, at least in part, to negative press attention relating to earlier interactions with the Chinese government: both Facebook and Twitter have been stung this year by criticisms for hosting advertisements and promoting propaganda tweets from Chinese state sources (Next Web, August 19). Twitter was further criticized in June for suspending Chinese-language accounts critical of the PRC government in advance of the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Massacre (Business Insider, June 2).

The account suspensions announced by these U.S. internet media companies have drawn a predictably harsh response from PRC officials. On August 20, PRC Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang (耿爽) asserted that “Chinese media use overseas social media to elaborate on China’s policy [and] tell China’s story,” and that PRC media outlets expressed “the attitude of the 1.4 billion Chinese on the situation in Hong Kong” (PRC Foreign Ministry, August 20). In a statement on August 28, Liu Liehong (刘烈宏), Director of the CCP Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission Office, issued a richly ironic statement that described the suspensions as an attack on China’s freedom of speech rights (Xin Jing Bao, August 28).

Although this particular PRC covert social media disinformation network has been at least partially disrupted, it is very unlikely that this is the end of the story. The low cost / low risk nature of such operations makes them an attractive option for authoritarian governments interested in swaying or polarizing opinion in more open societies—or at least, for sowing confusion and attendant inaction on the part of persons who might otherwise adopt positions contrary to CCP interests. Future days are likely to see further “coordinated inauthentic behavior” from cyber actors doing the bidding of the CCP.

John Dotson is the editor of China Brief. Contact him at: cbeditor@jamestown.org.

Notes

[1] For purposes of this article, the terms “covert operation” and “covert” are defined per official terms employed by the U.S. Government: “covert operation—an operation that is so planned and executed as to conceal the identity of or permit plausible denial by the sponsor.” [See: U.S. Department of Defense, DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (updated July 2019), pp. 54, https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/dictionary.pdf.] The term “disinformation” is defined per the terms of Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary: “false information deliberately and often covertly spread (as by the planting of rumors) in order to influence public opinion or obscure the truth.” [See: Merriam-Webster.com, entry for “disinformation,” https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/disinformation.] For a broader discussion of these issues, see: Dean Jackson, “Issue Brief: Distinguishing Disinformation from Propaganda, Misinformation, and ‘Fake News’,” National Endowment for Democracy, October 17, 2017, https://www.ned.org/issue-brief-distinguishing-disinformation-from-propaganda-misinformation-and-fake-news/.

[2] Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller III, Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election (“Mueller Report”), Vol. 1 Section 2 (“Russian ‘Active Measures’ Social Media Campaign”), pp. 14-35 (March 2019), https://www.justice.gov/storage/report.pdf.