Chinese Influence Faces Uncertain Future in Myanmar

Chinese Influence Faces Uncertain Future in Myanmar

At the beginning of February, members of Myanmar’s National League for Democracy (NLD) took their seats in the national parliament (People’s Daily, February 2). Though the transition was peaceful, Myanmar’s neighbors are anticipating political instability and ethnic unrest to escalate in the coming months, and Myanmar’s neighbors, including China, are anxious that the resulting population flows across borders could inflame ethnic insurgencies in volatile border areas. As the new government navigates these domestic and international currents, China is watching to see if the NLD will rush to embrace the West, or adopt a more cautious approach.

The NLD’s connections to Western nations are well established. Since its founding in 1988, the NLD has had a warm relationship with Western countries and received full support for its struggle against military rule in Myanmar. Indeed, the United States’ policy toward Myanmar, especially its decisions to impose, extend, and lift economic sanctions were reportedly influenced, even determined by the views of Aung San Suu Kyi, the NLD’s chairperson (Mizzima, January 23, 2012). In contrast, there was little engagement between the West and Myanmar’s military rulers, pushing the latter to build relations with China, India and member countries of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), who rarely criticized the generals for suppressing democracy in Myanmar. China in particular strongly backed military rule in Myanmar and provided it with generous political, diplomatic, economic and military support. This support helped the generals not only survive the West’s sanctions, but also consolidate their iron-grip over the country, prolonging the NLD’s struggle against military rule.

China seems “clearly anxious” that the Westward shift in Myanmar’s foreign policy was set in motion under President Thein Sein’s quasi-civilian government could “go even further in that direction” under the civilian and pro-West NLD government (Myanmar Times, January 8). However, the NLD cannot ignore the “logic of geography” stemming from the lengthy border Myanmar shares with China (Indian Express, June 14, 2015). While diversifying its partners to correct the extreme pro-China tilt of the past 25 years in Myanmar’s foreign policy, the NLD can be expected to avoid entering into a close relationship with the West. China will have to contend with competition from other countries, though it will remain a major source of investment and trade for Myanmar.

China’s Concerns

In 1988, Myanmar abandoned roughly four decades of non-alignment to become a close ally of China. The ruling junta, which was ostracized by the West for its violent suppression of protests in Yangon and other cities that year, turned to China for economic aid to help weather a crippling economic crisis and weapons to deal with domestic unrest and the threat of a Western invasion. The “explicitly close partnership” between the military rulers and China in the period between 1988–2010 saw China emerge as Myanmar’s largest foreign investor, its second largest trade partner and top military supplier. [1] Chinese cumulative investment in Myanmar in this period reached $9.6 billion, a third of which went into oil, natural gas and hydropower projects (Mizzima, February 22, 2011). China’s heavy investment in natural resources and transport infrastructure in Myanmar has facilitated extraction and import of its electricity, oil, gas, timber, and gems and has enabled it to acquire enormous influence over Myanmar’s economy. Myanmar’s value to China goes beyond its natural resources. Like the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), Myanmar provides an alternate overland route to the Indian Ocean, reducing threats to its energy supply lines through the South China Sea (China Brief, July 31, 2015; China Brief, April 12, 2006). Several of Myanmar’s ports were modernized by China and Chinese naval ships have docked in Myanmar’s ports in recent years (Youku, August 30, 2010).

China’s presence and influence in Myanmar has suffered setbacks in recent years. Political reforms initiated in 2011 triggered protests against China-backed infrastructure projects whose terms were much more favorable for China. The $3.6 billion Myitsone Dam project, for example, was to send 90 percent of the electricity generated to China (Mizzima, March 12, 2012). The Thein Sein government subsequently suspended a number of projects including the Myitsone project and the $1 billion Leptadaung copper mine project (Global Times, November 27, 2013). The 2011 reforms also prompted the West to begin lifting trade and investment restrictions, paving the way for more diverse sources of investment. For the first time in over two decades, Chinese investors faced competition from Western and Japanese investors, resulting in Chinese investment in Myanmar plunging from $12 billion in 2008–2011 to just $407 million in 2012–2013 (The Irrawaddy, January 1, 2013; The Irrawaddy, September 17, 2013; Global Times, March 27, 2014).

This decline in Chinese investment in Myanmar is expected to accelerate with the NLD’s ascent to power. Although there is disappointment in the West over Suu Kyi’s autocratic style of functioning and her silence on the violence unleashed against the Rohingya Muslim minority, the U.S. is expected to permanently lift sanctions if Myanmar’s military continues to respect the electoral verdict (The Irrawaddy, November 13, 2015). Cancellation of Chinese infrastructure projects would not only weaken Myanmar’s capacity to be China’s corridor to the Indian Ocean but also it could erode its grand plans for the Maritime Silk Route (MSR) initiative, part of China’s “Belt and Road” project to connect China with markets across Eurasia. Rail and gas-pipelines linking Myanmar’s Kyaukpyu port city with Kunming in China’s Yunnan Province are a key part of the MSR. The Myanmar side of the Kyaukpyu-Kunming rail project has run into trouble, though work continues on the Chinese side (Phoenix News, July 23, 2014; China Economic Net, December 7, 2015). If the NLD government scraps the project, it will further undermine the MSR (The Hindu, August 21, 2015).

China’s Outreach to the NLD

According to an analyst at Myanmar’s Institute of Strategic and International Studies, China “did not have to worry about competition from the U.S.” in the 1988–2010 period. By imposing sanctions and refusing to engage the ruling junta, the U.S. and other countries “voluntarily cut themselves out of Myanmar’s economic and strategic space.” That changed in 2011 when China had to contend with “mounting competition from Western countries and importantly Japan” in Myanmar.” [2] As it became apparent that reforms would lead to a larger role for the NLD in politics, non-engagement of the NLD was “no longer a sensible or practical strategy” (Myanmar Times, December 16, 2015).

With the aim of protecting its economic and strategic interests in Myanmar, China sought to broaden its base of support in Myanmar. It reached out to major political parties and civil society organizations at the national and regional level. China switched from ignoring the NLD and its leadership to courting them instead. Chinese envoys and officials visited NLD leaders, especially Suu Kyi, and NLD delegations were invited to China (Myanmar Times, May 1, 2013; Mizzima, May 8, 2013; The Irrawaddy, January 17, 2014).

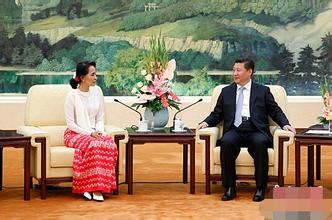

In July 2015, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) invited Suu Kyi to Beijing prior to the anticipated NLD victory in the general elections scheduled for November. This marked the first time China had invited an opposition leader from Myanmar to the country (Myanmar Times, October 26, 2015). Indeed, the state-run Global Times described the invitation of Suu Kyi as a “strategic move from China to safeguard ties with its southern neighbor,” since the NLD’s influence was “projected to grow in the upcoming elections” (Global Times, June 10, 2015). Suu Kyi met with Chinese President and CCP leader Xi Jinping, Premier Li Keqiang, former foreign minister and current State Councilor Yang Jiechi and a host of other top officials, treatment usually reserved for heads of state—not leaders of opposition parties. Clearly, China was preparing the stage for a new era in its relations with Myanmar.

What Lies Ahead

Despite anticipation of close relations between an NLD government and the West, Suu Kyi has shown herself to be “a hard-nosed and pragmatic politician and that in dealing with foreign policy issues she will be ruled by her head, not heart.” [3] Suu Kyi has also indicated that she will not oppose infrastructure projects simply because they are Chinese. As head of a parliamentary panel probing the Letpadaung copper mine project, she recommended continuing the controversial project, despite local opposition to it, on the ground that shutting it down would turn away foreign investors. She is “deeply aware that Myanmar needs Chinese investment.” [4] “We have to get along with [China] whether we like it or not,” she told villagers protesting against the project (Mizzima, March 13, 2015).

At the same time, Myanmar’s relations with Western countries can be expected to expand. For one, especially in the context of the United States’ pivot to Asia and Myanmar possibly emerging a “crucial piece” in that policy, Western interest and investment in Myanmar will intensify in the coming years. The NLD government would welcome investment from the West, “not because of its pro-West leaning but because it would be keen to diversify its partners and reduce dependence on China.” [5] Suu Kyi’s statement praising China’s Belt and Road initiative indicates that Myanmar under the NLD could continue to welcome Chinese investment, only it would seek to ensure that this investment is mutually beneficial (Xinhuanet, November 17, 2015).

New investment and trade partners from the West, Japan, and other Asian countries could put the NLD government in a “far stronger position” than its military and quasi-civilian predecessors to bargain with China on economic deals. In the 1990s, the junta was dependent on China and engaged Beijing from a position of weakness. This resulted in deals that were favorable to China. In contrast, the NLD government will have companies in the West eager to invest and trade with Myanmar. Burmese international affairs analysts emphasize that with “other options available it need not settle for what Chinese companies offer.” This could result in investment and trade agreements with China that are “more favorable to Myanmar” than they have been in the past. [6]

Despite its Western support, the NLD government is unlikely to put Myanmar on a pro-West path. It cannot afford to do so. China, after all, is a powerful neighbor that continues to wield immense influence in Myanmar. It can incite unrest and instability in Myanmar and fuel its ethnic insurgencies (Mizzima, March 5, 2015). Memories of China’s role in supporting ethnic insurgencies in Myanmar in the early post-independence decades, even instigating a Communist uprising in Myanmar in the late 1960s remain vivid in the country. Recent reports of Chinese complicity in Myanmar’s Kokang conflict and its support to ethnic militias like the United Wa State Army (UWSA) as well as allegations that it encouraged the UWSA and the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) to refrain from signing the ceasefire agreement indicate that Beijing is not averse to disrupting Myanmar’s peace process. Its influence over groups like the UWSA provides Beijing with a bargaining chip in negotiations with Naypyidaw (Mizzima, June 2, 2015; The Irrawaddy, July 13, 2015; Mizzima, October 9, 2015). At a time when it is struggling to put in place a peace process to end the country’s multiple ethnic conflicts, Myanmar cannot afford Chinese interference.

Conclusion

The NLD already faces multiple challenges, namely a highly politicized military, which remains exceedingly powerful. While the generals are by and large suspicious of China’s intentions, several prominent military officials have lucrative business dealings with the China and would likely oppose weakening ties (The Irrawaddy, October 23, 2015). Thus, the NLD could come under conflicting pressures from the military in the conduct of its China policy. At a time when it is figuring out its relationship with the military, the NLD will avoid opening up contentious subjects like relations with China. It will thus adopt a cautious foreign policy that seeks some distance from China, even as it avoids ruffling feathers among its own generals or in Beijing.

Myanmar’s history is replete with examples of its rulers adopting a cautious approach toward China. The swift recognition that its civilian government (1948–1960) accorded Communist China in December 1949 was reportedly aimed at deterring a possible Chinese invasion. Again, even when relations turned hostile in 1969, Myanmar’s junta sought rapprochement with China. [7] More recently, the Thein Sein government preferred suspending the Myitsone Dam project, rather than cancelling it. Similar caution will color the NLD’s approach to China, as well.

Over the past 25 years, Myanmar’s foreign policy had a pro-China tilt that saw it move away from the neutrality of the preceding 40 years. Under an NLD government, this tilt is likely to be corrected. It will seek to move Myanmar away from abnormal proximity to China to a more normal relationship. However, it will avoid replacing this with a westward tilt and refrain from entering into a close embrace with the West, especially of the United States While the NLD will be open to Chinese investment it will leverage its growing options to ensure that projects benefit Myanmar as well.

Dr. Sudha Ramachandran is an independent researcher and journalist based in Bangalore, India. She has written extensively on South Asian peace and conflict, political and security issues for The Diplomat, Asia Times Online, CaciAnalyst among others.

Notes

1. Sudha Ramachandran, “Sino-Myanmar Relationship: Past Imperfect, Future Tense,” Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore, Working Paper, no. 158, August 23, 2012, p. 6.

2. Author’s Interview, strategic analyst, Myanmar Institute of Strategic and International Studies, Yangon, January 5.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Ramachandran, n. 1, pp. 4–5.