Comac’s Homegrown Aircraft Goes Global

Comac’s Homegrown Aircraft Goes Global

Executive Summary:

- The Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (Comac) will likely take many years developing into a veritable world-class aircraft enterprise.

- Over 1,200 orders have been placed for the new C919, primarily from domestic state-owned airlines. Comac has delivered 5 single-aisle planes to domestic airlines and plans to scale annual production to 150 C919s by 2028.

- The company faces several challenges before entering the international market. It will need to obtain airworthiness licenses, find additional buyers, open overseas repair centers, and build resilience into its supply chain.

- Upstream and downstream aviation manufacturers in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) are working to localize technology amid rising geopolitical tensions.

In March, the Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (中国商用飞机; Comac) embarked on its first overseas demonstration tour throughout Southeast Asia (Xinhua Daily Telegraph, February 24). The state-owned company showcased its new single-aisle aircraft, the C919, at a series of airshows in Singapore, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Malaysia, and Indonesia. For the first time, the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) set a goal for the C919 to “go abroad (出国门)” in 2024 (People’s Daily, March 24).

Several headwinds could hinder Comac’s efforts to enter the international aviation market, despite the C919’s potential. Comac’s production capacity remains limited and, so far, the company has only delivered five C919s to domestic airlines (China News, April 28, 2024). Before exporting its products, Comac will need to secure overseas airworthiness licenses and build out a transnational network of service and repair centers. Finally, despite efforts to wean itself off western technology, Comac remains highly dependent on imported components. This leaves it vulnerable to geopolitical risk. As a result, the C919 is unlikely to rival incumbents like Airbus’ A320 and Boeing’s 737 for years to come.

Comac’s First Stop: Southeast Asia

The C919’s first overseas tour was intended to “lay the foundation for future market development in Southeast Asia,” according to Comac’s spokesperson (People’s Daily Online, March 14). The region is a natural launchpad for the C919, since thousands of weekly flights transit to and from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) within the plane’s navigable range (China Daily, January 29). By 2041, Comac forecasts the Asia-Pacific to become the world’s fourth largest commercial aviation market behind the PRC, Europe, and North America, with a fleet of nearly 9,000, mostly single-aisle, aircraft (Comac, November 13, 2022).

Before the recent demonstration tour, Comac had already made inroads into Southeast Asia. In 2022, a PRC-Indonesia joint venture called TransNusa Aviation became the first international airline to operate the ARJ21, Comac’s smaller, regional jet (Comac, December 19, 2022). China Aircraft Leasing Group (CALC; 中飞租赁), the owner of TransNusa, purchased the jets and leased them back to the airline (CALC, September 12, 2023). Comac then opened its first regional office in Jakarta to support the airline’s operations. Within the first year, TransNusa transported over 100,000 passengers between five regional cities on the ARJ21 (SASAC, February 29).

Last year, GallopAir (文莱骐骥航空), a Brunei-based airline, became the first regional airline to order a package of C919s with a deal valued at nearly $2 billion (AP News, February 26; 163.com, November 19, 2023). The purchase agreement adds to Comac’s reported backlog of 1,200 orders, primarily from domestic state-owned airlines (The Paper, April 28, 2023). China’s big three domestic airlines (三大航) agreed to purchase an additional 300 C919s in late April (Caixin, May 1).

To find more overseas buyers, Comac will likely look to international airlines with direct business links to the PRC, as in the case of GallopAir and TransNusa. The former, owned by Chinese businessman Yang Qiang (杨强) and set up by the Shanxi Tianju Investment Group (陕西天驹投资集团), hopes to commence operations of the ARJ21 later this year and the C919 in future years, following regulatory approval (Ch-Aviation, March 5).

C919 Seeks a Ticket to Ride

Comac will need to secure overseas airworthiness certifications before it can export the C919. As early as 2018, “airworthiness standards (适航标准)” were identified as one of 35 key core technologies that the PRC should seek to master, according to an article in a Ministry of Science and Technology-affiliated newspaper (CSET, May 2022; China Education and Research Network, September 24, 2020). While the plane received domestic approval in 2023, it has yet to receive certifications abroad. Cham Chi, the CEO of GallopAir, has said that the C919’s regulatory approval process in Brunei could take between two and three years, as the plane accrues more flying hours (Reuters, February 23). Approval for the ARJ21 in Indonesia took over two years, following the establishment of a working group between Indonesia’s Directorate General of Civil Aviation and CAAC (AIN, April 19, 2023).

The PRC has signed bilateral air services agreements with several ASEAN countries, but few certify PRC-made aircraft (see CAAC). Bilateral agreements with Laos and Cambodia are unique in that they include clauses recognizing the “airworthiness of aircraft manufactured in the People’s Republic of China” (CAAC: November 5, 2016; November 25, 2014). These deals, however, only apply to an earlier model of the PRC’s regional jet, the Xi’an MA60, which subsequently suffered from safety issues (WSJ, March 20, 2016). Beyond talking to Southeast Asian governments, CAAC is in consultation with administrators in Europe and the United States to facilitate Comac’s international expansion.

Comac’s Flightpath to Date

The goal to develop a large passenger aircraft (大型飞机) in the PRC has been a decades-long project. Before establishing Comac in 2008, the PRC government had experimented with previous models of commercial aircraft such as the Shanghai Y-10 and the MD-82, co-developed with the US firm McDonnell Douglas.

In 2005, the National Medium and Long-term Science and Technology Development Plan (2006-2020) listed developing large aircraft as a major national science and technology project (Gov.cn, December 20, 2005). In 2008, Comac was founded as a merger between China Aviation Industry Corporation I (AVIC I) and China Aviation Industry Corporation II (AVIC II). [1] The following year, the National Development and Reform Commission approved Comac’s plan to develop a large, single-body aircraft, the C919.

Comac received nearly $7 billion in seed capital from a combination of central and local governments, state-owned banks, and other state-owned enterprises. [2] Up to the end of 2020, it is estimated that Comac was granted access to nearly $72 billion of state subsidies (CSIS, December 7, 2020). However, Comac’s annual reports show losses of only $3 billion since incorporation, indicating that the company has used far less capital than it has had access to (Nikkei, June 20, 2023). As the C919 transitions from the design stage to the mass production stage, Comac will likely depend on greater state support. The company plans to scale annual production of the C919 to 150 aircraft by 2028 (Global Times, January 12, 2023). In early May, AVIC announced plans to build a new, 330,000 square meter facility in Pudong to expand the C919’s production capacity (Civil Aviation Resource Network, May 6).

Struggling to Lift Off From Technology Chokepoints

Despite the C919’s branding as the PRC’s first “independently developed” single-aisle commercial aircraft, the plane is composed of myriad components designed and manufactured by multinational firms (Comac.cc, accessed April 30). Comac operates according to the “main manufacturer + supplier” model like Boeing and Airbus. This means that the company purchases and then assembles parts from hundreds of different suppliers (Economic Times, December 17, 2023). As a result, Comac sits at the end of a vast and complex supply chain with suppliers located inside and outside of the PRC.

The rise of Comac has catalyzed an entire domestic ecosystem of “concentric circles (同心圆)” of innovation, spanning research, academic, and business organizations (Beijing Culture Review, December 11, 2022). According to Zhang Jun (张军), Secretary of Comac’s Board of Directors, the PRC’s aircraft manufacturing industry encompasses more than 1,000 companies, 100 research institutes, 70 universities, and 300,000 workers in 24 provinces and cities (Securities Times, September 21, 2023). Since Comac was established in 2008, 5,000 upstream and downstream aviation companies in the PRC have reportedly grown alongside the main manufacturer (Securities Times, September 19, 2023).

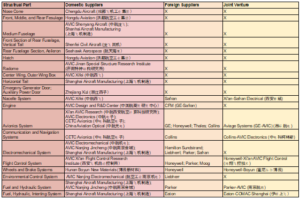

Estimates suggest that the PRC’s aircraft industry has been able to achieve a respectable 60 percent localization rate—measured by cost—for the C919 (eet-China, May 30, 2023). While PRC firms independently design and manufacture basic features of the aircraft, such as the aluminum alloy airframe, joint ventures and foreign enterprises supply the C919’s most advanced parts, from engines and avionics to air control and landing systems (Table 1). For instance, the C919’s LEAP-1C engine is produced by CFM International, a joint venture between GE Aerospace and France’s Safran Aircraft Engines (Military+Aerospace Electronics, February 29).

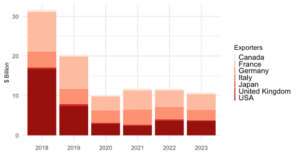

In 2023, France, the United States, and Germany were the three largest aircraft and parts exporters to China (measured at the HS-2 level), accounting for 35 percent, 32 percent, and 22 percent of China’s imports, respectively (Figure 1). China’s imports declined sharply during the Covid-19 pandemic and have yet to recover. In 2018 and 2019, the United States lost market share to its European counterparts following two fatal Boeing 737 Max crashes.

Five of the 35 key core technologies that the PRC government identifies as international “chokepoint (卡脖子)” technologies are directly related to modern aircraft. These include engine nacelles, avionics software, and aviation-grade steel (S&T Daily, September 24, 2020). On a tour of Comac’s Design and R&D Center in 2014, Xi Jinping stated that Comac should “independently develop products as soon as possible” (SASAC, August 1, 2022). Several years later, Chief designer of the C919, Wu Guanghui (吴光辉), explained that Comac seeks to “gradually improve localization” (People.cn, October 23, 2017).

Comac has an explicit goal to leverage international partnerships and joint ventures to promote indigenization and overcome technological “chokepoints.” The PRC’s pursuit of technology transfers from overseas firms in recent decades, especially in the commercial aircraft industry, has been a key part of Comac’s strategy in developing the C919. It has been described as “energetic,” and “always … the key priority” for officials, according to recent research. [3] The ability to achieve such transfers was enhanced following the empowerment of the National Development and Reform Commission in 2004-2005, with a 2005 deal with Airbus being a case in point. Industry insiders have noted that the nature of the sector in the PRC gave the country “incredible leverage” over foreign investors. In exchange for market access, multinationals have provided domestic Chinese manufactures with critical know-how and expertise. The plane’s avionics are developed by a joint venture between the PRC’s Aviation Industry Systems (AVIC) and GE Aviation, while Honeywell and Boyun New Materials build the plane’s brake system. Airbus and Boeing also operate joint assembly plants and research ventures with local partners (Airbus, April 6, 2023; Boeing, 2022).

The PRC has also used extralegal means to acquire aerospace technology. One example made public by cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike involved a cyberthreat actor known as Turbine Panda, which was linked to the Ministry of State Security’s Jiangsu Bureau (JSSD/江苏省国家安全厅) (Crowdstrike, October 2019). Turbine Panda targeted foreign component suppliers for the C919, including Ametek, Capstone Turbine, GE Aviation, Honeywell, Safran, and others via hacking and other means in order to gain access to intellectual property and industrial process data. When this was uncovered by the US Department of Justice, it ultimately led to the arrest of an MSS officer, Xu Yanjun, in 2018. [4]

In addition to partnering with foreign companies, the PRC is pursuing independent innovation across the supply chain under a project code-named “C9X9” (Bloomberg, February 25). For example, Aero Engine Corporation of China (AECC) is designing a replacement engine for the C919, the CJ-1000 (SCMP, February 11). Nonetheless, the CJ-1000 also relies on imported components such as the combustion chamber, manufactured by an Italian company, Avio, and the titanium alloy fan blades, produced by the UK’s Morgan Advanced Materials Group (MERICS, October 26, 2023).

Given the globalized nature of the aviation industry, the PRC is unlikely to achieve anything near self-sufficiency without investing tens of billions of additional dollars and several years on research and development. In the time that it takes the PRC to master existing technologies, global aviation leaders may already be producing more advanced products.

Export Controls Create Drag

Comac has faced several supply chain disruptions in recent years. In 2020, “aero-engine” technologies were included on the White House’s first Critical and Emerging Technologies List (Trump White House archives, October 2020). That same year, the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) placed several PRC aviation firms on the newly created ‘Military End User’ (MEU) list, including AECC, AVIC, and other aviation companies (BIS, accessed April 30). While Comac was spared from the MEU list due to its official status as a “commercial” manufacturer, many of Comac’s suppliers faced restrictions (Foreign Policy, February 16, 2021). Slowdowns in export licenses for Comac’s upstream vendors reportedly delayed the first delivery of the C919 by over a year (Reuters, September 27, 2021).

Nonetheless, the Commerce Department continued to grant GE licenses to sell its LEAP-1C engine to the PRC manufacturer (Reuters, April 7, 2021). GE argued that its engines would be difficult for Chinese manufactures to reverse engineer (WSJ, February 16, 2020). In 2021, the Department of Defense added Comac to the list of companies associated with the People’s Liberation Army, barring U.S. investors from owning equity in the company (DoD, January 14, 2021).

More recently, the objective of US export controls has begun to shift. In 2022, National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan stated that the United States is seeking “as large of a lead as possible” in key technologies (White House, September 16, 2022). In 2023, US Senators Marco Rubio and Rick Scott sent a letter to the Under Secretary of BIS requesting that Comac be added to the MEU list (Senator Rubio Senate Office, April 24, 2023).

Going forward, Comac faces the risk that supplies of US components will be cut off, especially if bilateral relations continue to deteriorate. These risks are likely to accelerate Comac’s drive for self-sufficiency.

Signs of Turbulence

Potential supply chain disruptions are one risk among several that international customers must consider when deciding whether to buy and operate the C919. So far, Comac does not run any overseas maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) centers—unlike Boeing, which operates five (Boeing, April 26, 2022). Comac has stated that it will “rely on customer’s own MRO” centers for servicing, but has offered to open new MRO centers in countries where airlines purchase at least 30 planes (COMAC SAMC, February 20; Reuters, February 23).

There is no guarantee that Comac’s products will find overseas buyers, even if it expands its international MRO presence. One problem is that many airlines already operate Boeing and Airbus products, and adding a third aircraft line would add to maintenance and repair costs in a notoriously low-margin industry. For this reason, Comac is likely to find more success with newly established airlines, such as TransNusa and Gallop-air, than with traditional airlines that may already have lock-in with Comac’s competitors (VOA, March 14).

The C919 does not offer much in the way of a cost or quality advantage. It is not fundamentally superior to western aircraft, since Comac still imports its most advanced components. Listed at $99 million per plane, the price of the C919 is also comparable to that of the 737 or the A320, which range between $110 and $120 million (Simple Flying, June 9, 2023). Since aircraft production is highly capital-intensive, Comac has been unable to translate the PRC’s labor-cost advantage into significant savings.

Finally, attempts to master existing aviation technologies could hinder Comac’s ability to create leading-edge technology. This problem is endemic to the PRC’s goal to move up the value chain more broadly. In the time that it takes Comac to scale production of the C919’s current design, Boeing and Airbus could already be producing more advanced products.

Conclusion

There may still be room for the C919 to carve out market share in the global aviation industry. Airbus and Boeing currently have order backlogs extending out well into the next decade. If neither company ramps up production capacity, the C919 may be able to make a dent in the international market. Furthermore, Boeing’s spate of safety challenges could persuade some customers to shift suppliers (CNBC, March 22). Chinese blogging sites like Weibo and Zhihu have been filled with schadenfreude over Boeing’s recent setbacks and the potential opportunity it presents to Comac (Weibo, March 17; Zhihu, January 6). The PRC may also be able to leverage its diplomatic influence and international business ties to find foreign buyers—several of Comac’s early international customers maintain direct connections to PRC investors.

Considering the many challenges Comac faces, however, it will likely be years before the manufacturer develops into a veritable world-class aircraft enterprise. Comac’s voyage abroad, in other words, is just beginning.

Notes

[1] Crane, Keith, et al. “China’s Industrial Policy and Its Commercial Aircraft Manufacturing Industry.” The Effectiveness of China’s Industrial Policies in Commercial Aviation Manufacturing, RAND Corporation, 2014, pp. 23–34. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/j.ctt6wq85j.10. Accessed 30 Apr. 2024.

[2] Crane, Keith, et al. “China’s Industrial Policy and Its Commercial Aircraft Manufacturing Industry.” The Effectiveness of China’s Industrial Policies in Commercial Aviation Manufacturing, RAND Corporation, 2014, pp. 23–34. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/j.ctt6wq85j.10. Accessed 30 Apr. 2024.

[3] Minnich, John, Scaling the Commanding Heights: The Logic of Technology Transfer Policy in Rising China (June 29, 2023). MIT Political Science Department Research Paper No. 2023-2, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4496386

[4] United States of America v. Yanjun Xu, 1:18-cr-43-TSB (2018). https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/5513700/United-States-v-Xu-Indictment-in-the-United.pdf