Diplomatic Data Signals Shifts over the Xi Era

Diplomatic Data Signals Shifts over the Xi Era

Executive Summary:

- Xi Jinping’s ascension to the office of State President led to an outburst in diplomatic activity that lasted until the coronavirus pandemic. Breaking with Hu Jintao’s later years, Xi made more trips than his Prime Minister and engaged in a greater number of state visits before 2020.

- Li Qiang’s replacement of Li Keqiang as Prime Minister has led to a reversion to the prior norm of the Premier conducting the most state visits. This is likely due to Xi’s higher degree of trust in Li than in his predecessor, and possibly due to Xi’s aging.

- The United States was in the top two countries in terms of diplomatic engagements during Xi Jinping’s first term, but interaction cratered after Trump took office. By contrast, Europe is the most popular destination, with a particular focus on France and Germany.

- Russia’s diplomatic relationship with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is uniquely intense, with annual visits every year and annual exchanges at the levels of prime minister, foreign minister, and national security advisor.

- Rhetorical support for Africa is not reflected in practice, despite the foreign minister’s traditional year-opening visit. Xi Jinping has made only 7 state visits to the continent, compared to 23 to Europe ex-Russia, which has also received nearly 1.5 as many visits of all kinds than its larger southern neighbor.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is responsible for the country’s day-to-day diplomacy. One of its key tasks is organizing incoming and outgoing diplomatic visits. [1] For instance, on November 11, the MFA announced that former Russian defense minister Sergei Shoigu, currently sidelined as Secretary of the Security Council of Russia, visited Beijing for the latest round of regular “strategic security consultations” between the two countries (FMPRC, November 11). Also this week, President Xi Jinping departed for Latin America to attend the APEC summit in Peru and make a state visit to Brazil (FMPRC, November 8). It is hard to judge the state of PRC diplomacy under Xi based on discrete events such as these, or to assess how exceptional Beijing’s ties with Russia really are. However, in the aggregate, data on all such visits reveals insights into how the PRC approaches its formal diplomatic engagements, and which parts of the world it prioritizes.

Analysis of all visits announced by the MFA since the beginning of former Chinese Communist Party (CCP) general secretary Hu Jintao’s (胡锦涛) second term in 2008 provides some preliminary answers to these questions (FMPRC, accessed November 13). [2] The PRC party-state is a hierarchical system in which the use of fixed phrases, assignments of rank, and compliance with precedent are important indicators (China Brief, September 20). This means that it is meaningful to track not just visits, but also the nature of the visit afforded to various partners. The seniority of the PRC representative, and whether the foreign representatives are invited or, as is often the case with the United States, met by “joint agreement (双方商定),” can provide a sense of Beijing’s diplomatic priorities.

For the purposes of analysis, visits have been tabulated using the following categories: the names and titles of PRC delegation leaders; the names and titles of the foreign interlocutor, whether the host or guest of the PRC delegation; the dates on which visits took place; and the type of visit, to include state visits (国事访问), official visits (正式访问), working visits (工作访问), normal visits (访问 or 访华), event attendances (出席), or others. If there are summits, forums, or bilateral commission meetings, those are listed too. There is some occasional variation in these categories. For instance, PRC representatives’ titles can differ, such as through the addition of Party titles when their interlocutor is the representative of another communist country (China Brief, July 26).

PRC Diplomatic Calendar Sees Recurring Meetings and Summits

Some aspects of the foreign minister’s schedule each year are relatively fixed and include a number of visits to specific countries or international fora and events. The minister has kicked off every year for 34 consecutive years with a visit to several African countries (FMPRC, September 5). In March or April, the Bo’ao Forum for Asia (博鳌亚洲论坛) is held on Hainan Island (Bo’ao Forum for Asia, accessed November 13). This is often an occasion for regional leaders to visit the PRC, especially in years where the president or premier is set to deliver a speech.

Different parts of the world usually receive PRC delegations during different times of the year. High-level PRC officials tend to visit Europe in the first half of the year, for instance. Visits to Southeast Asia most often take place in the fourth quarter, to coincide with the ASEAN summits in the second half of the year and the APEC summit around November, which the foreign minister and premier usually attend. Other regions are more scattered throughout the year, though Central Asian trips are generally linked to the timing of summits there. The BRICS summit is usually in the second half of the year.

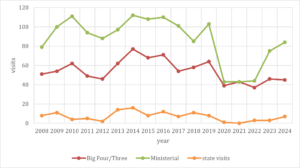

Figure 1: Outgoing Official Visits 2008–2024*

(Source: Author research. *Data for 2024 up to November 14.)

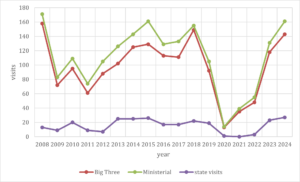

Figure 2: Incoming Official Visits 2008–2024*

(Source: Author research. *Data for 2024 up to November 14.)

Different levels of the PRC hierarchy attend the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summits, following a fixed order in which they occur. In general, the foreign ministers’ summit takes place between May and July, the heads of state meet sometime in June through September, ending the year with the heads of government between October to December. The president’s trip to SCO meetings is unique for summits in that it usually also entails a full state visit to the host country. BRICS summits have no set pattern but are generally summer affairs. As for the annual United Nations General Assembly sessions in September, the foreign minister usually travels to New York, though in 2023 the vice president went instead, as did the prime minister in 2016 and 2010. [3]

When the PRC hosts state visits, the visiting country’s foreign minister usually makes a preparatory trip in advance. The most common kind of incoming trip is one where the foreign official “attends (出席)” a meeting The PRC uses large summits to give many foreign officials the chance to meet PRC leaders without having to organize an independent visit. The most common outgoing—and second most common incoming—visits are “official visits (正式访问).” Less common on both fronts are the two lower ranked terms for visit, “fangwen (访问)” and “fanghua (访华).” In a standard year, the PRC receives in excess 20 “state visits (国事访问).” There are other kinds of visits too, though these are also less frequent. They include “working visits (工作访问)” and “official friendly visits (正式友好访问).” The latter has been used for delegations to Africa, Laos, Indonesia, and Japan in 2018 and 2019, as well as for isolated visits to Ethiopia (2012), Malaysia (2013), and North Korean (2011 and 2024). The only incoming visit that has been described as an “official friendly visit” was North Korea’s reciprocal visit in 2011.

Trends in Diplomatic Engagement Across the Xi Era

A burst of outgoing diplomatic activity is clear following Xi’s installation as State President until the start of the COVID-19 lockdowns. These visits have not fully recovered following reopening, according to the data. However, this is in contrast to relatively constant incoming traffic. More work on Hu Jintao’s first term should clarify the extent to which this has been the case since the early twenty-first century.

Under Xi, the world leaders who have visited the PRC most frequently are Hun Sen, who served as Cambodia’s prime minister 1998–2023, who made 13 visits, and Russia’s President Vladimir Putin, who has made 12. Third place in this ranking is shared by Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov and Thai princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn, each of whom have visited the PRC 10 times. [4] This strongly supports other evidence that Russia is currently the PRC’s strongest partner (China Brief, April 25).

Country rankings reinforce this finding. Russia is by far the most favored destination for PRC officials, as well as the second of third-highest source of visiting delegations. Interestingly, its proportional dominance in the former metric has declined since Xi’s first five-year term. Meanwhile, while the United States constituted an important destination for and source of diplomatic exchanges in Xi’s first term, this rapidly dried up coinciding with Donald Trump entering the White House in January 2017.

The bureaucratic reordering in favor of the Party at the start of Xi Jinping’s second term in 2018 shows up in the data. After the Central Foreign Affairs Leading Group (中央外事工作领导小组) was upgraded to Central Foreign Affairs Commission (CFAC; 中央外事工作委员会), Yang Jiechi (杨洁篪) and Wang Yi (王毅) were referred to by their title of the office director (办公室主任) also when receiving foreign ministers. Xi Jinping’s title of CCP General Secretary (中共中央总书记) is generally only invoked when his diplomatic counterpart is from a fellow communist country, which was already the norm.

Table 1: Top 5 Destinations for Official Visits per Term

| Top 5 outgoing countries in Xi’s first term | Top 5 outgoing countries in Xi’s second term | Top 3 outgoing countries in Xi’s third term (incomplete) | |||

| Russia | 38 | Russia | 14 | Russia | 11 |

| United States of America | 21 | France | 11 | France | 7 |

| France Germany |

12 | Germany | 10 | Germany Indonesia Kazakhstan South Africa |

4 |

| India | 11 | Japan Singapore |

8 | ||

| Indonesia United Kingdom South Korea |

10 | Indonesia Kazakhstan United Arab Emirates South Africa South Korea |

7 | ||

(Source: Author research)

Table 2: Top 5 Countries Hosted for Official Visits per Term

| Top 5 incoming countries in Xi’s first term | Top 5 incoming countries in Xi’s second term | Top 3 incoming countries in Xi’s third term (incomplete) | |||

| United States of America | 27 | Pakistan | 14 | Malaysia Vietnam |

9 |

| Thailand | 23 | Russia | 12 | Cambodia Kazakhstan Russia Thailand |

8 |

| Russia | 22 | Indonesia The Philippines |

10 | Indonesia | 7 |

| Cambodia | 20 | Japan Kazakhstan |

9 | ||

| France | 19 | Cambodia Uzbekistan |

8 | ||

(Source: Author research)

Xi Jinping

Since his ascension to the office of CCP General Secretary in October 2012 and to that of President in March 2013, Xi Jinping has overseen a new direction in PRC diplomacy. This shift is visible in diplomatic visits since he came to power (Figure 1).

Two changes stand out after Xi took over. First, there was an immediate uptick following several years of relatively low diplomatic engagement (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). The early years of the Xi era saw growth in both outgoing state visits by Xi and incoming trips at the ministerial level and above. Particular peaks are due to large-scale summits, such as the Beijing gatherings of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in 2018 and 2024, the first two Belt and Road Forums (BRFs) of 2017 and 2019, as well as the 2015 Second World War victory parade and the summit with Central and Eastern European countries.

Second, Xi has personally taken on a more active role. In the rankings of outgoing visits, the positions of president and prime minister swap places in 2013 (See Table 3). While Hu Jintao made fewer trips than his Prime Minister Wen Jiabao (温家宝) after 2010, Li Keqiang (李克强) was in Xi’s shadow throughout his first term, during which time only Foreign Minister Wang Yi made more trips abroad than Xi (Table 4).

Table 3: Number of Outgoing Visits by the PRC President and Prime Minister per Year

| Xi Jinping | Premier | ||

| 2024 | 8 | Li Qiang | 13 |

| 2023 | 4 | 5 | |

| 2022 | 5 | Li Keqiang | 1 |

| 2021 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2020 | 1 | 0 | |

| 2019 | 11 | 5 | |

| 2018 | 13 | 9 | |

| 2017 | 8 | 8 | |

| 2016 | 16 | 10 | |

| 2015 | 16 | 12 | |

| 2014 | 22 | 16 | |

| 2013 | 15 | 9 | |

| Hu Jintao | |||

| 2012 | 6 | Wen Jiabao | 20 |

| 2011 | 7 | 9 | |

| 2010 | 10 | 18 | |

| 2009 | 14 | 10 | |

| 2008 | 10 | 5 |

(Source: Author research)

This was a continuation of sorts, as Xi was also active in his capacity as vice president during Hu’s second term. In the period 2008–2012, Xi went on 41 overseas trips—more than all but three other officials (Hu, in third place, went on 47). Notably, this overlaps partially with the period 2009–2015, which saw a more active diplomatic role for vice presidents, according to the MFA data.

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the normal course of diplomatic engagement but appears to have reversed the trends in terms of Xi’s personal travel. While Wang Yi and Yang Jiechi kept up a large number of outgoing visits throughout the period, the onset of the pandemic put an end to an unusually active period for Xi. The MFA lists 77 trips during his first term as president, outstripping Hu in his later years in charge, but only 30 during his second. Two years into his third, and he has only been on 12 trips abroad so far. Prime Minister Li Qiang now travels more than his President, in contrast to his predecessor. In the aggregate, however, outgoing visits seem to not have reverted to pre-pandemic levels, though incoming visits from foreign diplomats appear to have resumed a regular frequency (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

Table 4: Top 10 Officials at the Ministerial-level or Above per Term by Overseas Travel

| Top 10 outgoing persons in Xi’s first term | Top 10 outgoing persons in Xi’s second term | Top 10 outgoing persons in Xi’s third term (incomplete) | |||

| Wang Yi | 152 | Wang Yi | 146 | Wang Yi | 38 |

| Xi Jinping | 77 | Yang Jiechi | 50 | Li Qiang | 18 |

| Li Keqiang | 56 | Xi Jinping | 30 | Xi Jinping | 12 |

| Yang Jiechi | 54 | Li Keqiang | 14 | Han Zheng | 11 |

| Liu Yandong | 32 | Wang Qishan | 14 | Ding Xuexiang | 9 |

| Zhang Gaoli | 28 | Sun Chunlan | 10 | Liu Guozhong | 8 |

| Wang Yang | 27 | Qin Gang | 9 | Qin Gang | 8 |

| Li Yuanchao | 16 | Hu Chunhua | 7 | Chen Wenqing | 6 |

| Ma Kai | 14 | Wang Yang | 6 | Shen Yiqin | 4 |

| Wang Yong | 11 | Wang Yong | 5 | He Lifeng | 3 |

(Source: Author research)

The above data suggests trends in PRC diplomacy fit with several reports on Xi Jinping’s exercise of power more broadly throughout his tenure. Scholarly accounts have characterized his first term as more vigorous and focused on centralizing power, as well as overseeing a shift to a more assertive foreign policy. [5] Over time, perhaps due to aging or consolidation of power, Xi has apparently felt more inclined to delegate tasks back to subordinates that he trusts (South China Morning Post, August 21, 2023). One related possibility for Xi’s more prominent role in diplomatic visits over that of his former prime minister Li Keqiang during his first term could also be attributed to the alleged rivalry between the two.

Russia

Russia has been the principal destination throughout Xi’s time in office and the second-most common source of incoming visitors (Tables 1 & 2). In 2013, Xi made his first state visit to Moscow, continuing a pattern of uniquely close interaction that the PRC has had northern neighbor for most of its existence (Gov.cn, March 22, 2013).

The PRC and Russia have held a state visit almost every year since at least 1999. In uneven years, PRC presidents visit Russia, while Russian presidents visit the PRC in even years (Tables 5 & 6). The only exceptions have been the pandemic years 2020 and 2021, Putin’s “official visit” in 2002, and Xi Jinping’s “attendance” at the World War II victory parade in Moscow in May 2015.

Table 5: PRC Presidential Visits to Russia

| President | Trip start | Trip end | Type | Forum |

| Xi Jinping | 22/10/2024 | 24/10/2024 | attend | 16th BRICS Summit |

| Xi Jinping | 20/03/2023 | 22/03/2023 | state visit | – |

| Xi Jinping | 05/06/2019 | 08/06/2019 | state visit | 23rd Saint Petersburg International Economy Forum |

| Xi Jinping | 11/09/2018 | 12/09/2018 | attend | Eastern Economic Forum |

| Xi Jinping | 03/07/2017 | 04/07/2017 | state visit | – |

| Xi Jinping | 08/07/2015 | 10/07/2015 | attend | 7th BRICS Summit; SCO Heads of Government Meeting |

| Xi Jinping | 08/05/2015 | 10/05/2015 | visit | Victory Parade 70th Anniversary end of WWII |

| Xi Jinping | 06/02/2014 | 08/02/2014 | attend | Sochi Winter Olympics Opening Ceremony |

| Xi Jinping | 04/09/2013 | 06/09/2013 | attend | G20; BRICS Informal Summit |

| Xi Jinping | 22/03/2013 | 24/03/2013 | state visit | – |

| Hu Jintao | 06/09/2012 | 09/09/2012 | attend | 20th APEC Summit |

| Hu Jintao | 15/06/2011 | 18/06/2011 | state visit | 15th Saint Petersburg International Economy Forum |

| Hu Jintao | 08/05/2010 | 09/05/2010 | attend | 65th anniversary of WWII victory |

| Hu Jintao | 14/06/2009 | 18/06/2009 | state visit | SCO Heads of State Meeting; 4th BRICS Meeting |

| Hu Jintao | 16/08/2007 | 17/08/2007 | attend | observe SCO counterterrorism military exercises |

| Hu Jintao | 26/03/2007 | 28/03/2007 | state visit | China Year opening ceremony |

| Hu Jintao | 16/07/2006 | 17/07/2006 | attend | G8 Dialogue with Developing Countries; collective meeting with the leaders of India, Brazil, South Africa, Mexico and Congo (Brazzaville) |

| Hu Jintao | 30/06/2005 | 03/07/2005 | state visit | – |

| Hu Jintao | 08/05/2005 | 09/05/2005 | attend | 60th anniversary of WWII victory |

| Hu Jintao | 26/05/2003 | 31/05/2003 | state visit | SCO Heads of State Meeting; 300th anniversary of Saint Petersburg |

| Jiang Zemin | 15/07/2001 | 18/07/2001 | state visit |

(Source: Author research)

The close relation between the two heads of state is complemented by active diplomacy at lower levels. Annual “Regular Meetings between the PRC Premier and the Russian Prime Minister” are supplemented by nearly annual visits by Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov to the PRC, and annual visits by the PRC’s foreign minister or state councilor for foreign affairs (with the exception of 2022). In addition, PRC Vice Premiers have played a significant role in meetings in Russia’s far east and, since 2018, the MFA has reported rare annual visits by the secretaries of the Central Political Affairs Commission and the Central Legal Affairs Commission (with the exception of the pandemic period 2020–2022). Russia’s former National Security Advisor Nikolai Patrushev was also a frequent guest in Beijing.

Table 6: Russian Presidential Visits to the PRC

| President | Trip start | Trip end | Type | Forum |

| Vladimir Putin | 16/05/2024 | 17/05/2024 | state visit | – |

| Vladimir Putin | 17/10/2023 | 18/10/2023 | attend | 3rd Belt and Road Forum |

| Vladimir Putin | 04/02/2022 | 06/02/2022 | attend | Beijing Winter Olympics Opening Ceremony |

| Vladimir Putin | 25/04/2019 | 27/04/2019 | attend | 2nd Belt and Road Forum |

| Vladimir Putin | 08/06/2018 | 10/06/2018 | state visit | SCO Heads of State Meeting; 4th China-Russia-Mongolia Heads of State Meeting |

| Vladimir Putin | 03/09/2017 | 05/09/2017 | attend | 9th BRICS Summit |

| Vladimir Putin | 14/05/2017 | 15/05/2017 | 1st Belt and Road Forum | |

| Vladimir Putin | 04/09/2016 | 05/09/2016 | attend | G20 |

| Vladimir Putin | 25/06/2016 | 25/06/2016 | state visit | |

| Vladimir Putin | 02/09/2015 | 03/09/2015 | attend | 1945 Victory Parade Beijing |

| Vladimir Putin | 09/11/2014 | 11/11/2014 | APEC Summit | |

| Vladimir Putin | 20/05/2014 | 21/05/2014 | state visit | 4th CICA Summit |

| Vladimir Putin | 05/06/2012 | 07/06/2012 | state visit | SCO Heads of State Meeting |

| Dmitry Medvedev | 13/04/2011 | 17/04/2011 | attend | BRICS Summit; Bo’ao Forum for Asia |

| Dmitry Medvedev | 26/09/2010 | 28/09/2010 | state visit | Shanghai World Expo; Soviet Martyrs Cemetery in Dalian |

| Dmitry Medvedev | 23/05/2008 | 24/05/2008 | state visit | – |

| Vladimir Putin | 14/06/2006 | 15/06/2006 | SCO Heads of State Meeting | |

| Vladimir Putin | 21/03/2006 | 22/03/2006 | state visit | – |

| Vladimir Putin | 14/10/2004 | 16/10/2004 | state visit | – |

| Vladimir Putin | 01/12/2002 | 03/12/2002 | visit | – |

| Vladimir Putin | 19/10/2001 | 21/10/2001 | working visit | APEC Summit |

| Vladimir Putin | 14/06/2001 | 15/06/2001 | SCO Heads of State Meeting | |

| Vladimir Putin | 17/07/2000 | 19/07/2000 | state visit | – |

| Boris Yeltsin | 09/12/1999 | 10/12/1999 | visit | – |

(Source: Author research)

Africa

The African continent receives substantial diplomatic attention from the PRC. Beyond the foreign minister’s symbolic first trip of the year, a number of officials travel to African countries as presidential envoys (国家主席习近平特使). These tend to include ministers, members of the National People’s Congress (NPC) Standing Committee, or chairs and vice chairs of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPPC). They are usually sent to attend presidential inaugurations and independence anniversary celebrations. Such delegations are also sent to Latin American countries, albeit with less frequency. In return, the PRC receives visits from African leaders, with the FOCAC and BRI summits often serving as peak periods for such interactions. African leaders have made more state visits to the PRC than their European counterparts, with 55 to Europe’s 42.

For the most part, diplomatic outreach to Africa occurs at lower-priority levels of engagement. Compared to Europe—which has fewer countries and a much smaller population—it is much more common for African leaders to “attend” an event rather than have a stand-alone “(official) visit.” In terms of state visits, Xi Jinping has only been on 7 state visits to Africa—fewer than once per year—of which 3 were to fellow BRICS member South Africa. By contrast, Xi has made 23 state visits to Europe (not including 4 to Russia), more than any other.

Table 7: Top 10 European (ex- Russia) Countries During the Xi Era by Diplomatic Engagement

| Top 10 destinations | Top 10 countries hosted | ||

| France | 30 | France | 30 |

| Germany | 26 | Germany | 18 |

| Switzerland Italy |

15 | Serbia | 16 |

| EU headquarters | 14 | Belarus EU headquarters |

15 |

| United Kingdom | 13 | United Kingdom | 13 |

| Serbia Spain |

8 | Hungary | 12 |

| Belgium Greece Hungary |

7 | Italy The Netherlands Switzerland |

11 |

| The Netherlands Portugal |

6 | Greece | 9 |

| Croatia Czechia Belarus |

5 | Denmark Poland |

8 |

| Finland Poland Slovenia |

9 | Czechia | 7 |

(Source: Author research)

Europe

Europe is a clear target of PRC diplomacy. Beijing seeks to promote the European Union’s (EU) strategic autonomy from the United States and protect and expand economic ties with the bloc (China Brief, May 24). The PRC has sent more delegations to Europe (including Russia) than to any other continent, with 50 percent more trips than to Africa. It has also received substantially more visits from European counterparts than from other regions, with Southeast Asia and Africa the next most frequent. While the diplomatic resources spent on European countries is out of proportion to the size of the continent’s countries, the reasons for doing so are supported by sound strategic and economic logic.

Among European nations, France has the highest diplomatic engagement under Xi, both sending and receiving 30 delegations, according to the MFA (Table 7). French President Francois Hollande was one of the first world leaders to make a state visit to the PRC after Xi’s elevation to the presidency. Germany ranks second, with particularly intense traffic during Angela Merkel’s tenure as Chancellor. Of note, interaction with Ukraine dropped off following the Maidan Revolution in 2014.

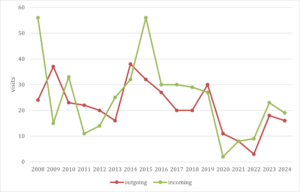

Visits to Europe (ex-Russia) peaked around 2014–5 but saw another uptick in 2018–9 (Fig. 3). Peaks in incoming visits can be explained in part by the China-CEEC Summit in 2015 and the Belt and Road Forums in 2017 and 2019. Following COVID-19, visits have resumed but are yet to reach the levels of the pre-pandemic period

Figure 3: Diplomatic Visits To and From Europe ex-Russia (2008–2024)

(Source: Author research *Data for 2024 up to November 14.)

United States

Diplomatic engagement between Xi’s PRC and the United States has been unusually volatile and has been relatively sparse since Donald Trump took office in 2017. During Xi’s first term, which roughly coincided with President Obama’s second term, the United States was the second most popular destination for PRC diplomats, with 21 reported trips (Table 1). It was also the most frequent source of visiting diplomats, with 27 trips (Table 2). This contrasts with only the United States receiving only 7 delegations and sending just 6 to the PRC during Xi’s second and third presidential terms combined.

Another unusual factor is how engagements with the United States are recorded by the MFA. Instead of detailing who instigated a visit, half the time writeups describe them as the result of a “US-PRC joint agreement (中美双方商定),” sometimes implying a degree of consensus between the two presidents.

Conclusion

The information outlined above provides a partial dataset that can be used as a departure point for data-driven analysis of PRC foreign policy. It demonstrates both continuities and departures between the Xi and Hu eras, as well as shifts during Xi’s time in power. It also helps clarify that PRC diplomatic interaction with Africa is far less intense at the senior levels, in contrast to the persistent focus on Europe. Finally, it highlights how limited interaction with the United States has become since 2017, in contrast to a uniquely intense relationship with Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

The MFA dataset is incomplete. First, it does not include visits that the MFA has, for whatever reason, not recorded publicly. It also does not include visits by delegations from other ministries, even though the PRC’s ministries of commerce and national defense maintain important international relations in their own right. And third, it also does not capture the growing role of CCP entities, including the International Liaison Department and the United Front Work Department. Nevertheless, the focus on high-level visits—cross-checked with the MFA website’s “Focus (专题)” section—is largely reliable, and can give a good sense of Beijing’s diplomatic priorities.

Notes

[1] The most important foreign policy organ in the PRC may be the CCP Central Foreign Affairs Commission (CFAC). However, the MFA remains important because of its control over day-to-day diplomacy. Analysis of CFAC remains beyond the scope of this article. See: Loh, Dylan M.H., China’s Rising Foreign Ministry: Practices and Representations of Assertive Diplomacy, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2024).

[2] The research for this article is based on a spreadsheet that was manually built by the author through processing all visits announced on the MFA’s Diplomatic Agenda (外事日程), as well as related stops and visits announced there (FMPRC, accessed November 13). The website does not go back all the way to 2008, so the Internet Archive was used to go back in time further than the live website allows (see Internet Archive, accessed November 13). Terms referred to are those of President, not General Secretary. The data is current up to the date of publication (November 14, 2024).

[3] Other summits, such as the Singapore-based IISS Shangri-La Dialogue or the Xiangshan Forum in Beijing, are the responsibility of the PRC’s Ministry of Defense and do not show up in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs announcements. Similarly, climate summits, including the recent COP29, also do not always show up on the MFA’s website.

[4] As the author’s database only lists the names of the most senior official in a delegation, it cannot be used for more granular analysis. For instance, it cannot provide information on the total frequency of a given official’s visits to the PRC, as it is possible they had visited on delegations of which they were not the most senior official.

[5] Doshi, Rush, The Long Game: China’s Grand Strategy to Displace American Order, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197527917.001.0001; Rudd, Kevin, On Xi Jinping: How Xi’s Marxist Nationalism Is Shaping China and the World, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2024).