Emerging EU Policies Take a Harder Look at Chinese Investments

Publication: China Brief Volume: 19 Issue: 2

By:

Like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), foreign direct investment (FDI) from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) now has a much broader reach than Beijing’s own backyard. It is well-known that Washington is actively working toward mitigating U.S. vulnerabilities to PRC investments in strategic sectors, and those that contain critical technologies and infrastructure. However, Europe, a region that also offers access to high technology desired by the PRC, is also taking a harder look at its own potential investment vulnerabilities. This process is leading to increasing debates and increasing regulation, both of which could impact the future course of Chinese investment in Europe.

While overall PRC foreign investment fell in 2017, investments in Europe were more resilient, increasing to 25 percent of the PRC’s global investment as compared to 20 percent in the previous year. PRC investment in Europe doubled in 2016 to $40 billion as compared to the previous year (Economist, October 4 2018). This figure dipped in 2017, but still remained robust at an estimated $33.7 billion (Merics and Rhodium Group, May 2018). Of the PRC’s top twenty foreign investment destinations in 2017, five were EU member states (PRC Ministry of Commerce, October 2018).

In order to defend its strategic interests, the European Union passed an investment screening mechanism in November 2018 targeted at the PRC. However, the voluntary nature of the mechanism, as well as concerns that the investment screening process may not be strict enough, has caused individual member states to rely on their own national laws and regulations. While there is a definite need to be more vigilant as individual member states decide how to defend their critical technologies and economic infrastructure from the transfer of intellectual property to the PRC, individual EU states should band together against the PRC’s vast economic weight and its tendency to press for bilateral, rather than multilateral, deals. Converging around France’s regime of investment regulation is a place to start.

France: “Long-Term Investments, Not Looting”

France has a longer history than its neighbors of scrutinizing foreign direct investment (FDI). The French Parliament first passed legislation in 2003 that enabled the government to screen and cancel foreign investments in national security sectors like defense (Légifrance, March 9 2003). The parliament later expanded the government’s jurisdiction in 2014 to cover sectors traditionally considered “critical”—such as energy, transportation, health and communications (Légifrance, May 15 2014). However, it is important to note that it was a proposal from a U.S. firm, General Electric, that served as the primary trigger for this expansion of French investment screening (Politico, June 26 2014).

It did not take long for PRC investment to become a central concern for French lawmakers. In the first month of Emmanuel Macron’s presidency, the newly-elected French president temporarily nationalized French shipbuilder STX, which owns the only shipyard in France large enough to construct naval vessels and warships (Defense News, September 27 2017). Macron made the move to halt the purchase of STX by Fincantieri, an Italian firm in a joint venture with a Chinese state-owned firm (Le Figaro, April 20 2017). The deal only went through after the French government received an unusual guarantee: namely, that it could renationalize STX if Fincantieri failed to safeguard dual-use technology from transfer to Beijing (Le Monde, September 27 2017).

Later, at the beginning of 2018, the French Ministry of Economy and Finance announced that it would strengthen its 2014 decree by expanding the definition of critical technology to include artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, robotics, big data, and semiconductors, thereby tightening rules against forced technology transfers (French Ministry of Economy and Finance, February 19 2018).

Most importantly, France is pushing a new approach to investment screening that could translate well to its neighbors, based on the concept of “golden shares” (Reuters, July 19 2018). Under this concept, the French government would grant itself golden shares that bestow special voting rights, such as the ability to block potential acquisitions in companies operating in critical sectors. Unlike other investment screening mechanisms, the European Commission has made it clear that EU law permits golden shares as long as countries can justify their use on the grounds of national security, or consumer and environmental protection. Experts have praised the concept on the grounds that it allows France to sell off ailing state assets while maintaining state influence in strategic industries (Reuters, July 19 2018).

Because of its relatively high debt-to-GDP levels, France cannot easily close itself off to increasing PRC investment (Eurostat, June 6 2018). In fact, President Macron’s first state visit in 2018 was to China, where he welcomed long-term PRC investment while pushing for better access to the Chinese market for French companies, and stronger protection for French intellectual property. President Macron’s finance minister, Bruno Le Maire, added a strong warning: “If investors come to France or Europe only to gain access to the best technology without benefiting France or any other European country then they are not welcome. There are looters in every country, and all of them need to understand that Europe has the means to protect itself” (Bloomberg, January 9 2018).

United Kingdom: A Two-Track System

Despite the negative economic implications of Brexit, the United Kingdom has paralleled France in tightening the regulation of FDI. Between 2000 and 2016, the United Kingdom was the largest destination country for new Chinese investment in Europe, with the country accounting for 23 percent of Chinese FDI during the same period. Like elsewhere in Europe, PRC investment in the United Kingdom has been concentrated in a handful of sectors: real estate and hospitality, information communication and technology, agriculture and food, and energy (Institut Français des Relations Internationales, December 2017).

Extensive PRC investment in sensitive areas of the UK economy during the tenure of former Prime Minister David Cameron—such as the Hinkley Point C nuclear power plant—resulted in calls for stricter investment rules under Prime Minister Theresa May. The decision to allow investment in Hinckley Point by China General Nuclear Power Group, a state-owned enterprise that has been accused of trying to obtain US nuclear technology for Beijing, resulted in the proposal of a new legal framework for foreign investments in Britain (The Guardian, December 21 2017). The new proposal, first aired for public consideration in September 2016, would allow the British government to intervene in investment projects where the government identifies national security concerns (Latham & Watkins, September 16 2016).

The UK proposal came along two tracks: a short-term proposal intended to change the Enterprise Act of 2002; and a longer term, far-reaching reform that culminated in an official white paper in July 2018. The Enterprise Act is the current legal framework that allow the Competition and Markets Authority to screen investments into the United Kingdom. In certain instances, the Secretary of State may intervene on matters relating to national security, media plurality, and financial stability (Herbert, Smith, Freehills, October 18 2017). The short-term proposal declared that deals involving companies with revenues of 1 million pounds (decreased from 70 million pounds) would be subject to review, and removed the requirements for a 25 percent control of supply threshold for review in the sectors of dual-use technologies, computing hardware, and quantum technology (Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy, June 2018).

As a component of longer-term reforms, under the proposed national security investment rules business owners are encouraged to notify the government of transactions that could have an impact on national security. After this notification, a Senior Minister is given fifteen days to screen the notification, during which time they can choose either to call for a national security assessment, or to decline to pursue further action. After the national security assessment is completed, the Senior Minister will then decide whether or not to intervene. While the submission of a notification is voluntary, Senior Ministers can still call for a national security assessment on any transaction, and companies that fail to comply can face criminal charges (Secretary of State for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy, July 2018). Initial estimates by the UK government indicate that there would be around 200 notifications a year.

The United Kingdom is clearly wary of PRC investments in certain sectors, as well as the extent of those potential investments. In its July 2018 announcement on tightening investment restrictions, the UK made it clear that it is looking toward its neighbors, such as Germany and other developed economies, to gather lessons on how to respond to Chinese FDI (Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy, July 24 2018).

Germany: “Keeping a Watchful Eye”

Recent high-profile PRC takeovers have also compelled German lawmakers to tighten their country’s investment restrictions. In 2016, Midea, a Guangdong-based company and one of the world’s largest manufacturers of commercial appliances, moved to takeover Kuka, Germany’s largest industrial robotics firm (New York Times, July 4 2016). The deal, which represented the biggest-ever takeover of a German company by a PRC buyer, raised suspicions because Midea offered a 60-percent premium on shares for the purchase. It also seemed to represent an unusual purchase for Midea, which primarily sells basic household appliances like air conditioners and washing machines (New York Times, July 4 2016; DW, August 17 2017).

Although Chancellor Angela Merkel did not attempt to block the Midea-Kuka deal, her then-minister for economic affairs and energy, Sigmar Gabriel, criticized PRC acquisitions on the grounds of national security risks. Midea’s acquisition only went through after it made legally binding assurances that it would protect Kuka’s intellectual property and customer data (New York Times, July 4 2016). The same year, another PRC firm with opaque ties to the Chinese Communist Party, Fujian Grand Chip Investment Fund, attempted to purchase German semiconductor firm Aixtron. The United States blocked the deal on national security grounds, as U.S. weapons systems use Aixtron’s technology; however, the German government had already withdrawn approval for the bid earlier that year (Reuters, December 8 2016).

Spooked by both incidents, Germany became the first among several EU countries to tighten its foreign investment policies in 2017, rewriting its laws to allow Berlin to block foreign acquisitions that involve critical technologies (Reuters, July 19 2018). These changes allowed the German government to block Yantai Taihai Group (a PRC firm that produces components for nuclear reactors) from buying the German machine-tool firm Leifeld in August 2016 (South China Morning Post, August 26 2018). Leifeld produces equipment for the nuclear and aerospace industries, creating concerns for technology transfer in these sensitive areas. In the same month, the German government also prevented the State Grid Corporation of China [国家电网有限公司], the largest utility in the world, from acquiring a 20-percent stake in a German transmission systems operator, citing a “major interest in protecting critical energy infrastructure” (Wall Street Journal, July 27 2018).

Despite such prominent examples of scuttled deals, there still remain concerns regarding PRC investment in Germany. In early 2018, Li Shufu, the chairman of Geely, one of China’s largest automotive manufacturers, acquired a $9 billion stake in Daimler, making him the firm’s largest shareholder (New York Times, March 15 2018). Li surreptitiously purchased his stake a year after Daimler had denied a proposal by Li to take a stake in the company, thereby raising questions about the effectiveness of the new German foreign investment law. The German government did not intervene in the transaction, but then-Minister for Economics and Energy Brigitte Zypries said the government must “keep an watchful especially watchful eye” on PRC investments (BBC, February 26 2018).

More importantly, Geely’s prospective partnership with Daimler aligns neatly with the PRC’s “Made in China 2025” [中国制造2025] national industrial policy. This initiative plans to transform China’s economy into a leading high-value economy, and has identified new energy vehicles as a key sector. Germany is the second largest destination for PRC investment in Europe, and the country’s advanced manufacturing and utilities sectors have accounted for more than two-thirds of recent Chinese investments in the country (Institut Français des Relations Internationales, December 20 2017). As a result of such lingering concerns, Berlin has already moved to tighten the investment restrictions issued in 2017, raising from 25 percent to 10 percent the threshold for investment scrutiny for a non-European firm in the defense, technology, or media sectors (Wall Street Journal, December 16 2018).

European Union: One Union, Many Mechanisms

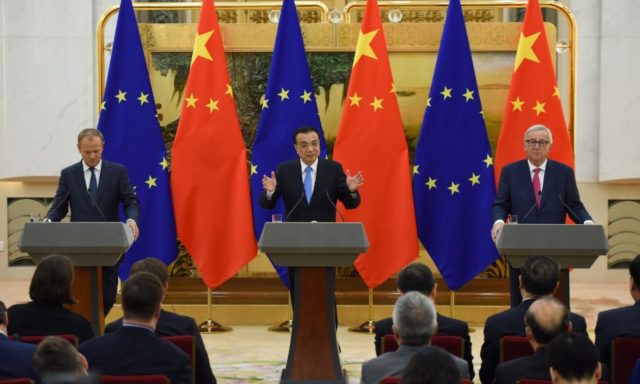

The Daimler case puts front and center the notion that individual European countries are ill-equipped to tackle predatory PRC investments. Before the case, in February 2017 the French, Italian, and German governments called for the European Commission to deal with the issue at a multilateral level (German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, February 2017). As individual member states started reforming their foreign investment laws, they also began pushing the EU to implement a unified mechanism, worried that PRC investment could weaken the EU as a whole. In addition, the PRC’s individual outreach to eastern European Union countries—both bilaterally and through the “16+1” mechanism—has caused concerns that China could undermine the collective security of the European Union (European Commission, September 13 2017). [1]

These dynamics, along with growing concerns that Europe was losing technological advantages to China, caused the Finance Ministers of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom to write a joint letter to EU Commissioner Cecilia Malmstrom in February 2017 (Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, February 2017). Since then, the European Commission has adopted an EU-wide screening mechanism for foreign direct investments (European Commission, November 20 2018).Of the twenty-eight member states in the European Union, there are only fourteen EU member states that currently have investment screening mechanisms in place. The mechanisms diverge between countries, varying between scope, investments covered, critical sectors, grounds for screening, and the design of the screening procedures. Prior to recent legislation, the EU only had a merger control regime that, in some cases, allowed for a review of FDI; however, this was based solely on the effects that the merger would have on competition in the EU.

To remedy some of these problems, the European Parliament approved a new mechanism in November 2018 that would allow EU member states to restrict inbound investment on national security grounds, and to protect critical infrastructure in the same fashion as some of its member-states like France and Germany. Additionally, member states will also have the option to comment on investments in other countries—regardless of whether the investment has been completed, whether the member state has a screening mechanism, or whether the investment is being screened. This information will then be passed onto the European Commission. However, the Commission will also have the ability to provide an opinion on investments if the Commission decides that it will affect the security or public order of the EU as a whole (European Parliament, June 12 2018).

Forging a European Consensus

The PRC, unlike Russia, does not seek to destabilize the European project, despite its preference for dealing with its member-states bilaterally (or within multilateral frameworks that China leads, such as the “16+1” Initiative). However, the PRC’s industrial strategy is a legitimate concern for both the European economy and Europe’s collective national security. While the European Union’s initial moves towards further investment restrictions are a welcome first step, the proposals are still voluntary and in the very early stages of implementation. Only time will tell whether European collective security is effectively protected through these new mechanisms.

France’s cautious yet open approach to FDI could serve as a model for improving upon the broader EU framework. The current EU framework agreed upon in November is an important first step, but the lack of standardization among EU countries and voluntary nature of the framework could lead to uneven implementation. By following the French model, and attentively vetting investments on a case-by-case basis—as well as presenting a united set of policies to guide all of its member states—the EU can protect its critical technologies and national security while remaining open to mutually beneficial business opportunities.

Ashley Feng is a research assistant in the energy, economics, and security program at the Center for a New American Security. She can be found on Twitter @afeng79.

Sagatom Saha is an independent energy policy analyst based in Washington, D.C. His writing has appeared in Foreign Affairs, Defense One, Fortune, Scientific American and other publications. He is on Twitter @sagatomsaha.

Notes

[1] The “16+1” is a name applied to an ongoing initiative by the PRC aimed at expanding economic and cultural linkages with states in Central and Eastern Europe. The 16 states involved in the initiative are: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia. (Investment and Development Agency of Latvia, June 2017).